Not every convict sent to Sydney during its fifty-four years as prison settlement was uncouth or illiterate. Most were ordinary working folk, undistinguished even in being singled out for exile for offences as petty as the theft of watches or sheep or boots. Some convicts were urbane, educated and multilingual, and skilled in supposedly foppish professions like art and architecture.

Charles Rodius (1802-1860) was one such convict: a portraitist, printmaker, architect, thief and man-about-town now counted among the most accomplished artists practicing in Australia in the first half of the nineteenth century. German born, Rodius had spent several years in Paris, studying and working as a teacher of ‘music, painting, drawing and languages in families of the first distinction’ before moving to London. In early 1829, Rodius defended himself against a charge of having relieved a woman, outside London’s Royal Opera House, of the smelling bottle, tickets, opera glass and handkerchief contained in her ‘reticule’. He was described at the time of his trial as ‘a young foreigner, dressed in a most fashionable style.’ But despite his appearance – and suitably effete defence that the stolen goods in his possession were gifts to him from ‘ladies who had been his pupils’ – Rodius was found guilty and transported to New South Wales for seven years.

That an agreeable chap could be dealt such a disagreeable hand was by no means a singular occurrence and a number of artists of Australia’s colonial period bear histories just as shifty. Landscape painters Thomas Watling and Joseph Lycett and miniaturist Richard Read senior, for example, were all convicts despatched to New South Wales for forgery. And the Van Diemen’s Land art scene was graced, thanks to the convict system, with the presence of figures such as Thomas Griffiths Wainewright, a painter and essayist who was convicted of forgery but suspected of much darker transgressions; French-born artist Charles Costantini, who served two separate sentences for theft; and successful Birmingham printmaker Thomas Bock, transported for his part in the plying of a young woman with a preparation designed to make her miscarry.

Despite the taint and shame of their criminal status, Rodius and several of his similarly skilled contemporaries met with success in the makeshift societies of the Australian colonies. The administrators of these settlements kept keen eyes open for useful convicts and proved amenable to the overlooking of a man’s disreputable or anomalous circumstances in cases where his abilities could be applied to the service of the state. Just as Bock, soon after he came to Hobart, was employed in engraving bank notes, Rodius’s skills as a draughtsman were snared with his assignment to the Department of Public Works on his arrival in Sydney in December 1829.

Rodius ‘attended most of the Civil and Military officers... as a Teacher of Drawing, in all its various branches’, as well as providing plans of proposed and existing buildings for the colonial architect’s office. Fortunate in a choice of profession for which there was substantial official demand in Sydney, Rodius was fortunate too in finding in the settlement a climate wherein private patronage of artists – convict or not – was ripening. Improvements in the colony’s economic prospects were attended by larger numbers of free settlers, the most prosperous of whom created a willing and robust market for art. The commissioning of paintings was a typical way of preserving the proof of one’s social and material success and, in much the same vein, prominent gentlemen employed artists to school their wives and children in the genteel accomplishments of drawing and watercolour. Those who had employed Rodius as a tutor to their children – including Chief Justice Francis Forbes and deputy commissary general James Laidley – were among the citizens that supported his application for exemption from government service, and when this was granted in 1832 he began to earn his own living as an artist. Blending suavity with professional ability and powerful connections, Rodius adapted seamlessly to Sydney’s fluid social fabric and the evidence of its texture, along with that of the character of the colonial art scene, is plentiful in his work.

Rodius’s output encompassed those subjects that were the staple of artists working in Australia during the first half century of European settlement: views of the new and still intriguing world at a time of ‘progress’; portraits of those populating it; and souvenir images of its ‘exotic’ fauna, vegetation and Indigenous people. Rodius joined artists such as Conrad Martens in the picturesque landscape enterprise, drawing Sydney and the harbour and creating portraits of the elegant villas established in places such as Darlinghurst and the Rocks. But it was his portraits of people that formed the most substantial part of his oeuvre.

Rodius created images of many Sydney identities, including road builder William Cox and his wife Anna; ex-convict doctor and politician William Bland; John Dunmore Lang, clergyman and reformer; plus newspaper proprietor Edward Smith Hall. Perhaps the most recognised of these portraits is that of Ludwig Leichhardt, drawn by Rodius on the explorer’s triumphant return from his first expedition in 1846. In true artist-as-entrepreneur fashion, Rodius cashed in on Leichhardt’s hero status by issuing lithographed editions of the drawing, just as he did with images of other bankable subjects – such as convicted murderer John Knatchbull, whose lurid crimes engendered ghoulish public interest in his trial and execution in 1844. Rodius usually represented his subjects seated or in profile and presentably attired in their daywear. These characteristics, allied with his modus operandi of simply rendered works on paper in pencil, charcoal and pastel, resulted in portraits that evoke a sense of the everyday.

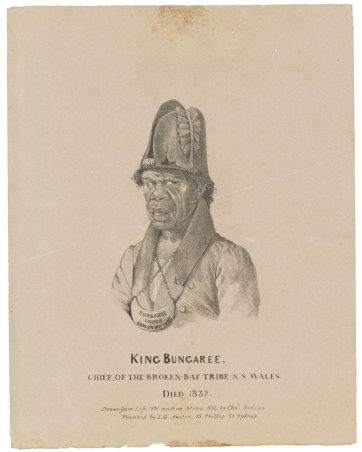

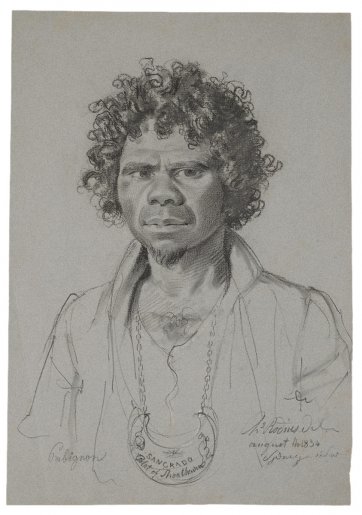

But it was with his portraits of Aboriginal people that Rodius demonstrated his true dexterity. He produced the first of his drawings of ‘the most prominent Aborigines of the various tribes of New South Wales’ in the early 1830s and by 1834 the Sydney Herald was advising readers that ‘it is the intention of the Artist to submit to the Public, a series of lithographic copies of the work … at such charges as will place these interesting copies within the reach of all classes.’ These images as well as Rodius’s second series of portraits of Aboriginal identities, produced in the 1840s, appealed as collectible souvenirs of colonial life and found their way into the cabinets of curiosity kept by those with an interest in science and ethnography. While some of Rodius’s likenesses of sitters such as Bungaree – a man from the Broken Bay area who accompanied Matthew Flinders and Phillip Parker King on their voyages of discovery – veer towards caricature, others, such as his images of men and women from the Shoalhaven district, are disarming in their softness and sensitivity, rendered with an effortless but assured use of line. In quick, economic gestures and with simple materials Rodius managed to convey in these works the complex intersections of black and white societies, showing the dignity of these sitters along with clues – not always subtle – to the corrosion of their traditional way of life. Rodius depicted his Indigenous subjects in European clothes, representing Bungaree in his trademark military hat and jacket (Governor Macquarie’s cast-offs) and wearing the gorget by which Aboriginal people were singled out by the colonisers for their loyalty or assistance.

The distinct characteristics of Rodius’s work are exemplified in his self portrait of 1849, recently acquired by the National Portrait Gallery. Long rumoured to exist but concealed from historical notice in the private collection of one of his great-great grandchildren, it shows Rodius as a middle-aged gent, the plump and proud face suggesting his education and charm as well as providing ample proof of his delicacy and abilities. Family lore holds that Rodius drew the portrait to occupy himself while his wife gave birth to their daughter, Theresa. The portrait later passed to Theresa and was then passed from her along four generations of the family. By the time of the self portrait, Rodius had been a free man for several years and was a successful artist. After two short-lived marriages (to Maria Bryant in 1834, and sixteen-year-old Harriet Taylor in 1838) he made another in 1841 to Harriet Allen, the daughter of Josiah Allen, an artist transported to Sydney for forgery in 1817. The second of Rodius’s major twists of fortune occurred in 1856 when he suffered a stroke that left him partly paralysed and unable to work. He died a pauper four years later, his death taking place in a building designed by yet another forger and convict, Francis Greenway.

While perhaps less lauded or well known, the work of Charles Rodius parallels and sometimes surpasses that of other artists whose Australian careers originated in convictism, both in its quality and its potency as a document of this accidental aspect of our art history. His self portrait is thus a rich and exceptional artefact, showing us an artist whose skills, but for a momentary lapse of respectable behaviour, would have been lost to the faces and flavour of colonial Sydney.