Freud works extremely slowly: a painting may take from several months up to more than a year to complete, and the etchings – a less familiar but nevertheless integral part of his studio practice – also each tend to occupy many months of his time. Often awkward and anything but idealising, Freud’s portraits are based on a frank scrutiny of his subjects and intense reflection on their human nature. Their uneasy presence extends from his self-professed ‘horror of the idyllic’, and his belief that art should be true to life – and therefore disturbing. He has said, ‘I think of truthfulness as revealing and intrusive, rather than rhyming and soothing’.

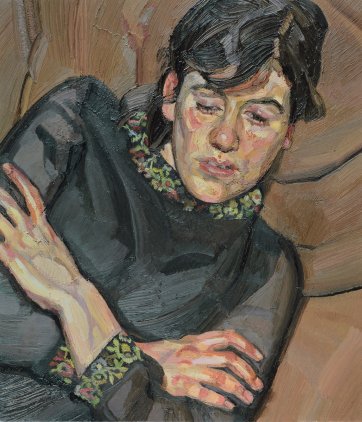

Freud has repeatedly described his work as autobiographical. ‘It is about myself and my surroundings. It is an attempt at a record. I work from the people that interest me and that I care about, in rooms that I live in and know. I use the people to invent my pictures with, and I can work more freely when they are there.’ Cameras and theatrical poses play no part in Freud’s process, and he does not generally make use of symbolic props or other narrative devices. All this helps us to understand that his portraits are not portraits in the traditional sense: they are not meant to flatter his subjects or to help promote public personae. They are not intended as public statements, but rather as private exchanges between artist and sitter. Executed at extremely close range, almost always within the confines of his studio, Freud’s paintings and etchings fully embody the intimacy of this process, whether they are of monumental scale, as are some of his best-known canvases, or of the small size that characterises a large percentage of his paintings and many of his etchings.

One of Freud’s best-known subjects was Leigh Bowery, the outrageous performance artist and transvestite fashion designer from Australia who was notorious on the London club scene in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Freud met Bowery after a performance at the Anthony d’Offay Gallery in 1988, and Bowery subsequently sat for some ten canvases and four etchings over the course of four years, from 1990 through 1994 (he died on 31 December 1994). Although many of these paintings are of an overwhelming scale that seems to correspond to Bowery’s outsized presence and massive physique, which fascinated the artist, the etchings form part of a more intimate subset of works that bear witness to another, quieter and more reflective side of the man. These works concentrate on his head, and in many of them he is shown sleeping, his serene, unconscious demeanor contrasting with the brash, confrontational stance of the larger paintings. In the etching Large Head 1993, Bowery’s pliant features and slack skin are almost palpably rubbery, their malleability somehow coexisting with the solid weight of his being.

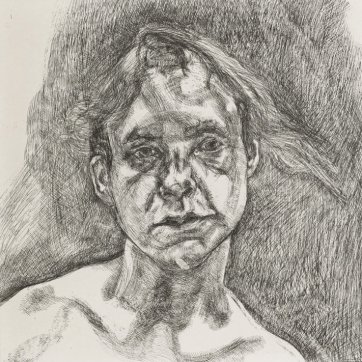

Equally compelling is Self-Portrait: Reflection 1996, Freud’s only self portrait etching. His most sombre print by far, it has an almost morbid mood, derived in great measure from the inexorable repetition and reinforcement of Freud’s etched lines, as well as the mysteriously dark and nuanced way in which the work was printed. The obsessively etched grooves re-create almost literally the pits and craters of his own careworn face; this effect is enhanced by the abundant tone that Freud’s printer, Marc Balakjian, left on specific areas of the plate. Freud’s self portraits often include the word ‘reflection’ in their titles, a word that refers both to the mirror the artist uses to scrutinise himself and to his state of mind in doing so. The sagging flesh that he renders here is, as poet Nathan Kernan has evocatively described it, ‘crumpled into angular highlights like a discarded paint rag’.

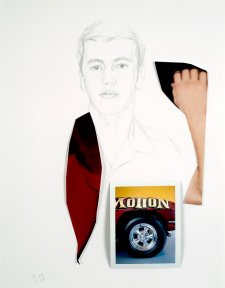

The etching is related to the numerous painted self portraits that Freud has executed periodically over the years. An example from 2002 is the one that is probably closest in format and in spirit to this print. In the painting, Freud’s repeated attempts at the face are left visible in the build-up of paint in coagulated patches and calloused highlights. These heavily impasted corrections correspond to the reinforcements and revisions of line that are evident in Freud’s etching; in both instances they are tangible records of his long, slow process, each line or dab another visible marker of time that has passed. Among Freud’s more recent portraits are a related painting of 2004 and a 2005 etching of art critic Martin Gayford, who wrote about his experience as a sitter and the different effects of the two works in an article for Apollo in 2005 entitled, ‘It’s me looking at him looking at me’. According to Gayford, ‘It was planned that the etching should follow the painting. Right from the first sitting, however, [Freud] announced that it would be “very different”. And so it turned out to be: optically, technically, and in feeling.’ The painting was a night portrait, executed under artificial light, while the etching was an afternoon picture and created in daylight from the window. ‘That in itself altered the emotional temperature,’ Gayford recalls. ‘The afternoon is a quiet time while the evening has hints of excitement: both of us were a little tired, running down toward that late afternoon dip when Lucian takes a rest. We talked less … I was engulfed in a bout of intense work, which perhaps the etching registered. Certainly, I look more anxious and tense.’ Indeed, the etching registers a more troubled mood than that in the painting, with ‘the face elongated and crumpled as if I had been subject to torsion by the violent forces in the air that seem to swirl around my head’.