‘At Christmas 1969’, wrote Tom Uren in 1971, ‘the world saw for the first time the beautifully blue and white and fragile planet earth against a forbidding, lifeless foreground of the moon … This new look at “spaceship earth” may be the greatest benefit from the Apollo programme and the new conscience it has engendered in us all may make the cost of that programme worthwhile.’

Uren is one of a number of figures in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery – some better known for their contributions in other areas – who were pioneers or substantial supporters of the seminal Australian environmental campaigns of the early 1970s and 1980s.

The poet Judith Wright McKinney, whose 1955 portrait by Charles Blackman was acquired by gift of her friend Barbara Blackman in 2000, was a co-founder and president of the Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland between 1962 and 1976. Through the 1960s and early 1970s Wright was devoted to protecting the Great Barrier Reef and surrounding areas from threats on many fronts. In 1966 she wrote to Barbara that if Blackman really wanted to see the Reef ‘he’d better hurry. It’s all being eaten away by rampaging tourists and Crown of Thorns starfish in conjunction … Nor do I recommend you go to Stradbroke which is being eaten away by rutilesand mining.’ International interest in oil reserves on the reef was increasing; Veronica Brady records that in 1969 the Queensland Minister for Mines had declared that ‘where there are minerals it is our duty to encourage extraction’. The following year, the ominous climate of which is evoked in Wright’s poem ‘Australia 1970’, Blackman illustrated a poem of hers in the Sydney Morning Herald, showing the Great Barrier Reef pocked with oil derricks.

In 1970 Wright began to lobby for the preservation of Fraser Island, targeted for sand mining. Patrick White, who had visited the area to research a novel, told her that ‘any kind of artist who has been to that island will remain affected by it for ever.’ In early 1975, David Marr records, White wrote personally to Gough Whitlam saying that he was ‘appalled and depressed’ by the proceeding mining plans. The reply from Whitlam – ‘I want to reassure you as best I can’ – fell short of allaying his anxiety.

As Wright gathered support for the conservation of unique areas of Queensland, Tasmania’s first dedicated environmental campaigner, Olegas Truchanas, did his best to stop industrial development of unsullied regions of his adopted island, particularly the glacial jewel Lake Pedder. Tom Uren, whose portrait by Ralph Heimans was purchased for the National Portrait Gallery in 2001, was one MP who spoke up for Lake Pedder on the Australian mainland. Born in Balmain, Uren grew up in the Sydney suburb of Manly and contested the Australian heavyweight boxing title before heading for the war, during which he was a prisoner of the Japanese. After some years working as a store manager, in 1958 he became the Labor member for Reid in western Sydney. In 1970, as Opposition Spokesman on Housing, Urban Affairs and the Environment, he first moved to establish a government fund for restoring historic homes. That year, too, he made his first parliamentary speech about environmental issues, calling attention to the fact that the Shell Oil refinery at Clyde was blowing thirty tons of sulphur dioxide into the air every day and leaking oil into the Duck River, a tributary of the Parramatta River that ran through his electorate.

More broadly, however, expressing the visionary idealism that Heimans captured in his painting of Uren, in this speech of 1970 he recalls proclaiming people’s right to ‘surroundings reasonably free from man made ugliness’, and the ‘duty not to blight’ – phrases that he also used in his Fabian Society pamphlet of mid 1971, Urban Australia and the Australian Environment: What We Can Do. In October 1971, Uren called for a halt to the plans to drown Lake Pedder; in the winter of 1972 he proposed to Gough Whitlam that if poor rainfall persisted until after the election at the end of the year, it might give a Labor federal government time to arrest the inundation. After the 1972 election, Uren was made Minister for Urban and Regional Development, while Moss Cass became Australia’s first-ever Minister for the Environment. At their urging, Whitlam wrote to the Labor Premier of Tasmania, ‘Electric Eric’ Reese, suggesting a joint Commonwealth/ Tasmanian committee of enquiry into the options for Lake Pedder. He was rebuffed. Although the Commonwealth pressed ahead with an enquiry, Uren recollects that as time wore on disagreement developed amongst his colleagues about what should be done about the lake, based in part on personal differences and power struggles thathad little to do with concern for the remote beauty spot. Amidst calls for a moratorium on the flooding, the Deputy Prime Minister, Tasmanian MP Lance Barnard, argued that the lake in its natural form was very difficult for ordinary people to enjoy; expanded, it would be much more accessible to families who would be able to drive right up to its edge. Uren writes that at the time, for various reasons, Whitlam was disposed to support his deputy rather than Cass, who later broke ranks alongside Uren to oppose the decision in caucus. The lake was sunk, but a far-reaching legacy of the campaign was the establishment of the world’s first Green political party, formed in Tasmania in 1972.

In 1973 Uren and Cass announced the Committee of Inquiry into the National Estate, which was to lead to the establishment of the Australian Heritage Commission three years later. Uren’s good friend Judith Wright was a committee member (and the first place listed on the National Heritage Register in 1977 was Fraser Island). Architectand ecological advocate Milo Dunphy, a veteran of the Lake Pedder campaign and others to save areas of the Warragamba catchment from clear felling and mining, was appointed to the committee instead of Uren’s first choice, the high-profile union activist Jack Mundey, who was engaged in a libel suit at the time.

As Uren was assembling his committee members Jack Mundey, whose portrait by Lewis Morley was acquired by the National Portrait Gallery in 2007, had been Secretary of the NSW branch of the Builders’ Labourers’ Federation for five years. Mundey grew up on a dairy farm in Queensland before moving to Sydney to try out for the Parramatta rugby league side in 1948. Employed in a metalworking factory, he joined the Federated Ironworkers’ union and then the Communist Party, of which he was later president for some years. In the early 1960s, as limits on building heights were lifted in Sydney and the city entered its great building boom, he led rank and file workers in action to improve safety and sanitary conditions for workers. As secretary of the NSW BLF he encouraged union members to become informed and involved in social movements including feminism, gay liberation, Aboriginal land rights, Vietnam and apartheid.

In his early forties, Mundey became the scowling face of the ‘green bans’ that established an international precedent for environmental protection through direct united action rather than government intervention or legislation. The green bans – as opposed to ‘black bans’, imposed by unions militating for better pay or conditions for their members – arose out of the so-called Battle for Kelly’s Bush, which took place in the Sydney suburb of Hunters Hill in 1970-71. The building firm AV Jennings had planned to build a substantial number of homes in the suburb on native bushland on the Parramatta River. Thirteen women who lived in the area, including doctor Joan Croll, spearheaded an action to mobilise opposition to the development. In her portrait by John Brack, given to the National Portrait Gallery by Frank and Joan Croll in2001, the neatly-coiffed Croll looks anything but the activist in her enviable string of pearls and dainty t-bar shoes. Indeed, more than half of the ‘Battlers’ lived on Prince Edward Parade, one of the loveliest streets on Sydney’s lower north shore. At the height of the Battle for Kelly’s Bush, Prince Edward Parade was dubbed ‘Red Square’, because the women involved had managed to co-opt the communist Mundey to their cause. Notoriously, when representatives of AV Jennings suggested they would press on and build in Hunters Hill using non-union labour, workers on a Jennings office project in North Sydney declared that if one tree were disturbed in Hunters Hill, the half-completed building would remain unfinished forever, ‘as a monument to Kelly’s Bush’. In the four years following the first green ban at Kelly’s Bush, some forty similar bans were imposed by unions, scuttling many millions of dollars’ worth of development on sites with historical or ecological heritage value. In some quarters, Mundey is now credited with preventing the demolition of much of inner Sydney’s built heritage in the 1970s and 1980s, including areas of The Rocks, Centennial Park, Woolloomoolloo, and the Pitt Street Congregational Church. In many of his stoushes he was supported by generally conservative figures, horrified by threats to areas of personal significance to them. Patrick White, for example, joined the Friends of the Green Bans – and made his first public speech, standing alongside Mundey – out of concern at plans to convert his local green space, Centennial Park, into a giant sports centre.

As the Battle for Kelly’s Bush played out in Hunters Hill, members of the band that would become Midnight Oil began playing together on Sydney’s northern beaches. By the end of the 1970s the Oils had evolved into a live act of extraordinary power. Although fans at heaving venues such as Narrabeen’s Antler Hotel were barely able to make out the words to their songs in the shirts-off mayhem, Midnight Oil’s lyrics engaged angrily with their sociopolitical moment. Their fourth album, Place Without a Postcard (1981), featured acover photograph by Robert Butcher of a scarred treeless landscape, and tracks such as ‘If Ned Kelly Was King’, demanding ‘Heavy machinery loud in the outback/Dreamtime developers they make all the sound/Where will we be when they leave us a quarry?’

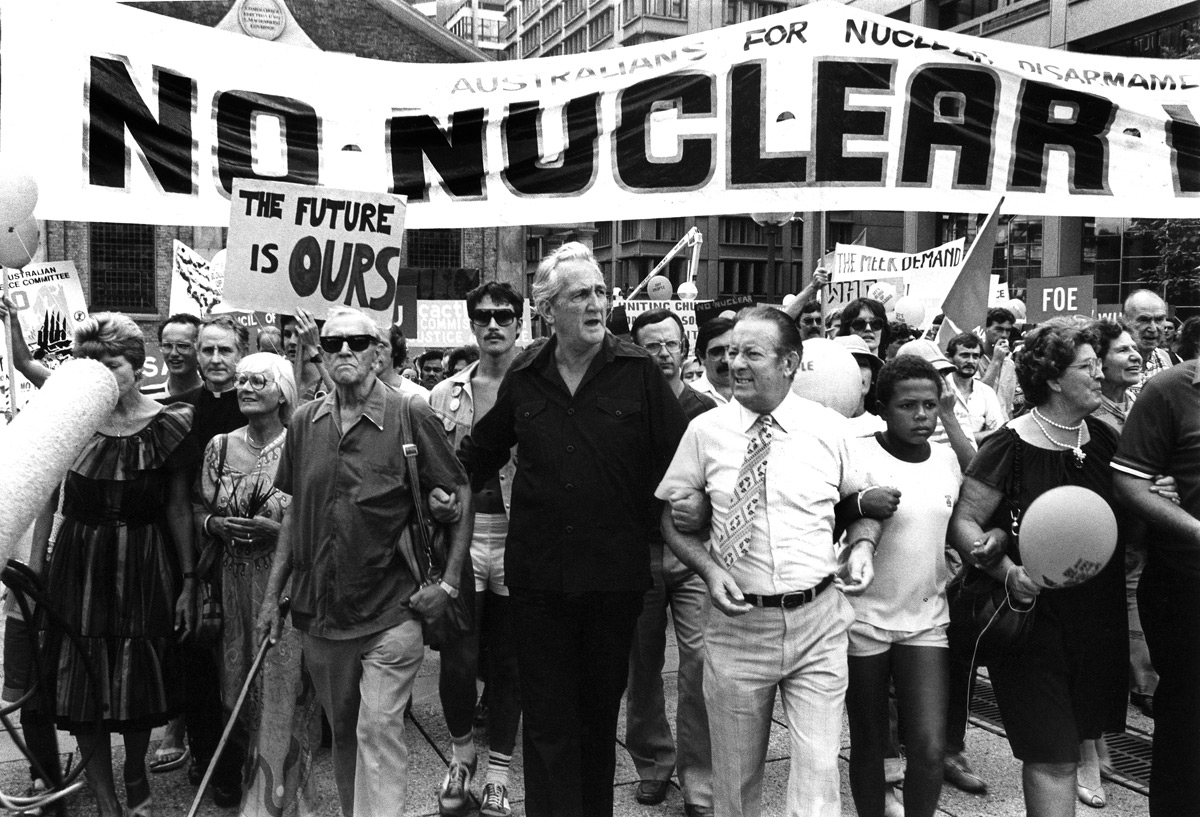

In 1983, in an international climate of increased public involvement in protest, the Australian local news was dominated by environmental demonstrations on two fronts. The first was the Tasmanian NO DAMS campaign, making highly professional and effective use of photographs by Peter Dombrovskis,a wilderness photographer mentored by Olegas Truchanas. The second was the anti-nuclear movement. In February 1983 Midnight Oil helped organise the Stop the Drop concert in Melbourne, and headlined the event. That year, Tom Uren and Peter Garrett marched together at the head of an anti-nuclear protest. In 1984, when Tom Uren and Patrick White walked side by side at the front of an Australians for Nuclear Disarmament march and Peter Garrett stood unsuccessfully for the Senate on behalf of the Nuclear Disarmament Party, Midnight Oil released the album Red Sails in the Sunset, featuring sinisterly surreal cover artwork by Tsunehisa Kimura of the Sydney Harbour Bridge spanning an expanse of cratered red dirt, a bomb-like ball glowing lava-hot beside the Opera House. The following year, the Oils’ EP Species Deceases came with album notes on the theme of Hiroshima forty years on. Including the great track ‘Hercules’, Species Deceases was an exasperated exhortation to action: ‘Come to your senses and care/16 million I can’t hear you at all’, Garrett cried.

Judith Wright wrote sympathetically to a conservationist friend in the early 1970s that he must be sick of fighting and being ‘on everybody’s ratbag list’. Over time, however, the high-profile ‘ratbags’ represented in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery have come to be recognised as conservation heroes. Truchanas is commemorated in the Truchanas Huon Pine Forest in the Wild Rivers National Park. Tom Uren was made ao in 1993 and Jack Mundey in 2000; Peter Garrett became an am in 2003, the year after the National Portrait Gallery commissioned its group portrait of Midnight Oil from eX de Medici. Jack Mundey was on the Sydney City Council from 1984 to 1987 and has been a Patron of the Historic Houses Trust of NSW since 2002; he has honorary doctorates from the University of New South Wales and the University of Western Sydney. Mundey, Uren and Garrett are all designated National Trust Living Treasures, as was Wright until her death in 2000.