There is little doubt that photography is the most pervasive and popular medium for portraiture today. Photography is a truly democratic medium for making portraits. There are more cameras and photographers in the world than ever before in history. In Australia, most families have a camera.

Indeed, many have several cameras and the one-camera family is almost a thing of the past. Once the sure sign of a professional photographer, it is no longer unusual for an individual to have several cameras. Of course, such cameras are rarely high-end devices. Every mobile phone seemingly has a camera built in to it. The digital revolution in photography has made cameras very inexpensive and, dispensing with film and processing, cheap to run. We are a long way from that moment in 1847 when it cost ten shillings (well over a month’s salary for the average man then) for a daguerreotype portrait in Douglas T Kilbourne’s studio in Melbourne.

And anyone can take a photo these days. Cameras are simpler to use and the arcane science of optics and of the darkroom has been surpassed by an intuitive contemporary technology that ensures the amateur is as able as the professional to take a successful photograph. And if the technical prowess of the photographer is no longer important, then perhaps the measure of a photographer’s fame is in their ability to capture an iconic image, ideally of celebrity.

Increasingly it seems as if the status of the sitter is the criteria for ‘great’ portraiture. We are a Who Magazine generation, part of a global vampire cult feeding on fame and the famous, where recognition is the most important thing. What happened to old fashioned skill? What happened to the notion that skill in understanding lighting and composition mattered? It is vital that the photographer has the control to engage the viewer, no matter whether they are famous or not, at least according to renowned master photographer Helmut Newton, who advised that ‘My job as a portrait photographer is to seduce, amuse and entertain.’

The craft of portrait making is at the heart of the first National Photographic Portrait Prize. This makes it a natural fit with the National Portrait Gallery. The Prize was announced on 12 July and, within minutes of the official opening, the first submission had been lodged. By the closing date, a vast number of entries had been submitted, nearly 1500 portraits in all. Judges Andrew Sayers, Director of the National Portrait Gallery, curator Michael Desmond and Naomi Cass, Director of the Centre for Contemporary Photography, had their work cut out for them but through a rigorous and exacting process, the number was pared back to seventy-five works to be exhibited in the Gallery. From these finalists a winner will be selected to receive the truly magnificent prize of $25 000 donated by the Gallery’s major supporter, Visa International. The judges’ selection for the exhibition was not based on the fame of the photographer or on the sitter’s celebrity, rather on the power of the individual photograph to create an impact on the viewer and communicate something about the sitter; in short, its success as a portrait.

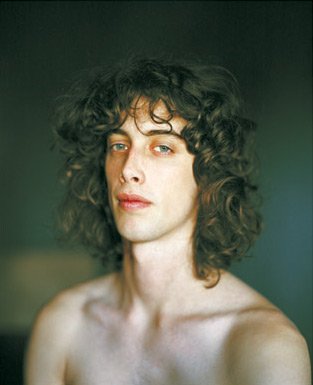

A wide range of portraits have been chosen for the exhibition to conjure up a surprising variety of emotive responses. There are portraits that offer social commentary, glamour, gritty realism, even fantasy, as well as the occasional brush with fame. While the entries are all portraits, there is great variety in the approach taken in each work and the sheer inventiveness of the photographers is impressive. The exhibition does not constitute a snapshot of Australia or the Australian people, that is to say that as a group, the portraits do not give an even-handed view of our Australian demographic. There is a predilection for the picaresque or exotic subjects, or for significant moments, and there are many sentimental portraits as you would expect.

Interestingly, there are few celebrities or illustrious sitters in the display, unlike the Archibald Prize. The exhibition does however, include Phillip Adams AO by North Sullivan, actors David Gulpilil AM by George Fetting and Geoffrey Rush by William Yang, singer/songwriter Paul Kelly by Martin Philbey, and artist Lindy Lee by Robert Scott-Mitchell. In addition, there are some well-known visages that perhaps might be classified as anti-heroes – rebel in hiding Alfredo Reinado, by Lindsay Moller, Mamdouh Habib by Renee Nowytarger and activist Gary Foley by Rod McNicol. There are some remarkable photographs of Indigenous subjects in addition to those just mentioned, including a powerful image of Manakgu, a traditional land owner, taken at Coopers Creek, Arnhem Land by Hari Ho.

Sentiment has a strong presence in the exhibition (and featured in the great number of the submissions) where the attachment to the subject, be it child, parent or lover, is evident. Trent Parke’s endearing portrait of his son under the shower, Jem Parke, records the bond between photographer and sitter, producing a tender image of ephemeral beauty and innocence. Yumi on fire, one and a half hours before the eclipse of the moon by Zorica Purlija, a portrait of the photographer’s daughter, is an eerie testimony to the power of the camera to edit a wondrous moment from life and capture it on film.

A surprising number of pregnant portraits were submitted, clearly an emerging trend. The judges selected only one, an image of astonishing graphic power. Di Barrett’s portrait of Faye shows her in an almost Byzantine setting, rich, lush and redolent of promise. The complement to birth is also present in the images of mortality in the exhibition. A number of portraits show the effect of sickness and age on the sitter. Ingvar Kenne’s Lazarus-like portrait of Martin Mishkulnig is a study in sterile hospital whites that shows the heroism of everyday life in withstanding tragedy. The ephmerality and sheer fragility of life is visible in Dad at 93 years old by Gary Heery, or the humorous yet melancholic image of the elderly subject, Mary, photographed by Bo Wong, as she almost merges into the floral wallpaper.

While there is a touch of tristesse in some portraits, there is also much good humour. Rocking the boat by Mark Tedeschi shows the fearless Nicholas Cowdery AM QC in a small dinghy, literally rocking the boat as he has done as New South Wales Director of Public Prosecutions. Alan Lesheim depicts Elia Elton (and friends) as Ewok-like inhabitants of the deep forest with the thrill of a ‘Where’s Wally’ quest in finding the friends mentioned in the title of the photograph. Jules Boag will raise a smile with her group portrait, The hunting lodge, a parody of the grand manner with a surreal twist.

The poetry of everyday life is evoked by Mark Kimber in his portrait of Dan on winter solstice eve that is as much about mood as likeness. The light washing out Dan’s features suggests a moment of transcendence.

Many of the portraits in the exhibition remark on beauty and transience. Simon Obarzanek twists this theme in his neo-gothic image of the quotidian in his portrait of an anonymous young girl, 10pm – 1am #7. Ordinary folk appear in the ambitious group portrait by Ruby Davies, Water as life: the town of Wilcannia and the Darling/Baaka, showing the population of Wilcannia posed in the dry riverbed of the Darling River. This could almost stand as a metaphor of Australia, her people and the challenge of the future.

The National Photographic Portrait Prize 2007 boasts a strong field of innovative and insightful portraiture. This, the inaugural display, promises to be an exciting showcase for established and emerging photographic work. The 2007 Prize will be the last major exhibition in the National Portrait Gallery’s Old Parliament House premises. The National Photographic Portrait Prize is intended to be an annual event. The next will take place in the new building in March 2009.