Matthys Gerber’s portrait is as bold as the paintings that have been made by his subject, Indigenous Australian artist George Tjungurrayi. Born around 1945 in the desert region near Kiwirrkura Western Australia, Tjungurrayi is known as one of the most inventive of the painters associated with the desert art movement.

Tjungurrayi’s familial language groups encompass Pintupi, Luritja and Ngaatjatjarra, whose geographically defined country covers thousands of kilometres of terrain from the Northern Territory across the Western Australia border and into the Gibson Desert. In 1976 Tjungurrayi visited the settlement at Papunya, about 200km north west of Alice Springs in the Northern Territory and began to make paintings based on the ancestral stories for which he is custodian.

The community of Papunya is famous for the role it has played in the genesis of one of the most important art movements in Australia, the desert art or ‘dot painting’ style of Aboriginal art. Papunya was established in 1961 as a government settlement that brought together five main groups of Aboriginal people from the surrounding region, those mainly of Arrente, Anmatyerre, Luritja, Walpiri and Pintupi descent. It was the last settlement to be established under the government’s policies of assimilation of Aboriginal people, where settlements such as Papunya were to act as places in which Aboriginal people could be educated in the customs of white Australia. By 1971 with a population of about 1 000, half of who were aged sixteen or under, Papunya’s resources were stretched and social unrest was commonplace. That year the new art teacher at the Papunya Special School, Geoffrey Bardon, instigated the creation of a mural painted on the school walls in traditional Aboriginal design, led by senior men Billy Stockman Tjapaltjarri and Long Jack Phillipus Tjakamarra who were working as school yardsmen at the time. The mural depicted the Honey Ant Dreaming, a story that related directly to local land formations, two hills that are the petrified bodies of Honey Ant ancestors. The mural generated a passionate response from the Aboriginal community in Papunya, many of whom began to produce paintings on portable surfaces including cardboard and tiles. With designs drawn from traditional sand painting and body decoration, and representing a living sense of Indigenous belief and law, these early paintings were understood by their makers as a powerful expression of Indigenous tradition and culture. In 1972 the Papunya Tula Artists Cooperative was established to manage the production and sale of paintings.

George Tjungurrayi began painting for Papunya Tula Artists in 1976, and became well known for his innovative and striking painting style based on vividly coloured and optically intense geometric stripe patterns. Tjungurrayi is custodian of the Tingari stories, the details of many of which are secret in nature. His paintings often refer to sites where ceremonies have taken place, including the freshwater lake island Mamultjulka, and the water soakage in the claypan Kirrimalunya. Tjungurrayi’s paintings are held by major collections, including the National Gallery of Victoria and the Holmes à Court Collection.

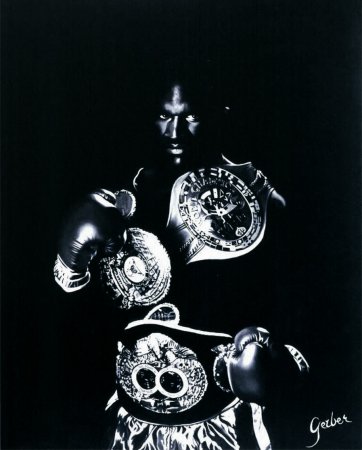

It was precisely the intensely striking abstract qualities of Tjungurrayi’s paintings that appealed to Sydney-based artist Matthys Gerber. Born in Delft in The Netherlands in 1956, Gerber arrived in Australia as a young man in 1972. He currently teaches at the Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney, and has exhibited his work extensively in Australia, Europe and the USA. Gerber’s work is resolutely contemporary and he has worked within the traditions of landscape, portraiture and abstraction for over twenty years. His landscape paintings of the early 1990s are well known. Drawing upon the conventions of kitsch domestic landscape painting, Gerber daringly created large-scale images of grandiose alpine mountain scenes, bucolic forest streams, and thundering waterfalls. These paintings were a challenge to elitist concepts of taste, but they demanded to be taken seriously. They spoke about public conventions of beauty, while entering into a dialogue with the history of Pop Art and its strategies of quotation and appropriation of mainstream imagery. Gerber applied a similarly analytical attitude to the painterly genres of the nude figure, abstraction and portraiture. Indeed, the portrait has remained an enduring interest for the artist. In 1992 Gerber created an imposing larger-than-life sized portrait of the African American boxing champion Evander Holyfield. In the painting the fighter’s muscular body emerges from a field of deep black. Holyfield’s dark-toned skin is set apart from its surrounds by a sweat-like sheen. Gerber titled this painting ‘Black painting’, an allusion to its status as an abstract painting as well as a recognisable portrait, and establishing a tension between the two artistic approaches. In 1993 Gerber commissioned street artists in Paris to make imaginary portraits of a young Jesus Christ. The resulting images conformed to a popular idea, the young Jesus depicted with youthful or feminine features, flowing hair and soft beard. And in 1994 Gerber used passport photographs – a form of portraiture conventionally understood as having little artistic merit – as the basis for a series of portraits of his artist peers.

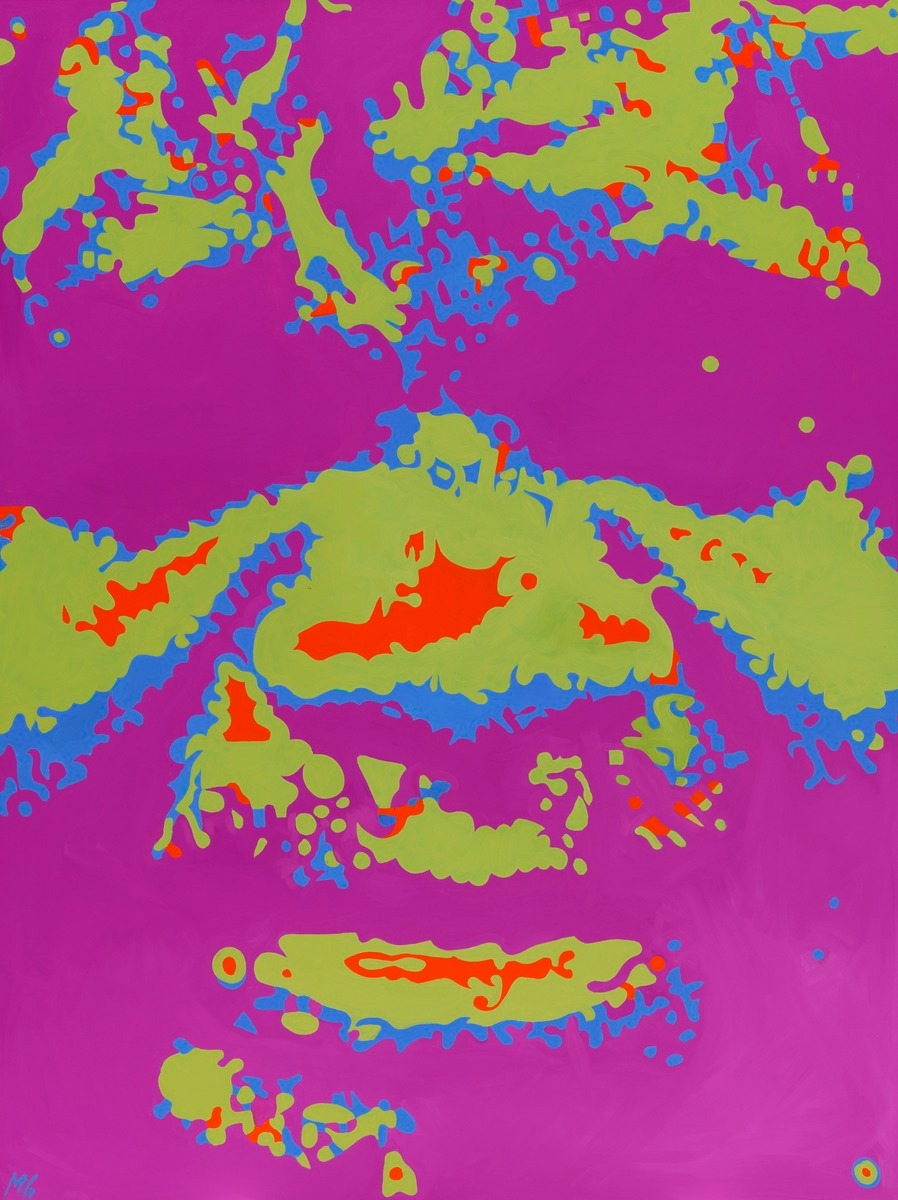

The portrait of George Tjungurrayi in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery was painted by Gerber as one of three portraits in similar style. Using photographs as source material, Gerber made large close-up portraits of artists he considered to be significant contemporary abstract painters. Along with Tjungurrayi, Gerber made portraits of Swiss artist Olivier Mosset and Melbourne artist Gary Wilson, and the three paintings were exhibited together in the exhibition of contemporary painting It’s a Beautiful Day, shown at the Ian Potter Museum of Art at the University of Melbourne and the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2002-03. In these works Gerber was interested in bridging the gap between abstract painting and portraiture. He has selected as his subjects artists who are known for their own innovative abstract painting styles, and has chosen to depict them in a manner that draws upon the conventions of abstraction as well as portraiture. Gerber’s portrait of Tjungurrayi is a translation of the photographic image, the tonal qualities of the photograph interpreted as areas of vivid colour: orange, blue, green and purple. Tjungurrayi’s broad features are recognisable, and his face is abstracted, creating a complex visual tension in the image. The translation of tone into colour gives the impression of camouflage, evoking the camouflage portraits by the celebrated American Pop Artist Andy Warhol. The shimmering optical effect of the layering of colour in Gerber’s painting makes reference to the western history of abstract art and to the powerful and innovative optical nature of Tjungurrayi’s own paintings.

When the painting was on display in 2002-03 George Tjungurrayi saw the work for the first time. As Gerber recounts, Tjungurrayi gave the painting the ‘thumbs up’. In this arresting portrait Gerber has captured a compelling and elusive presence.