The richness of portraiture is attested to by this simple proposition: a gallery can be devoted solely to portraits and yet can present a complete visitor experience. There are no national still-life galleries or landscape galleries but there are several national portrait galleries. Why? Well, leaving aside the way in which national portrait galleries fulfil an important role in creating composite pictures of national identity, portrait galleries are fundamentally about people - about you and me. They remind us that we all have a life in which there are triumphs, disappointments, achievements, good years and bad years - things that give each a preciously individual shape.

'Gallery' implies an institution in which art values are uppermost. Yet in the case of the portrait gallery, artistic quality is only half of the story. When we see a portrait hanging on a wall there is a simple and basic question we all ask: 'who is it?'. The quality of the text is an important aspect of the way portrait galleries tell their stories. A portrait gallery presents visual images and the words that accompany them are related fragments of biography.

I am going to tell you a story, which to me highlights the way in which it is not possible to fully understand a portrait without an accompanying text. In July 2001 an armed man walked into a clinic in East Melbourne. He was apprehended by a security guard whom he shot dead. The gunman was taken into police custody. He refused to give his name and he had nothing on him by which he could be identified. Two days after his arrest, the police had to take the unprecedented step of releasing a picture of the man with a plea to the public to identify him.

But the initial optimism that 'Mister X' would be quickly identified soon looked misplaced; despite the efforts of police, the man had still not been identified 11 days after the shooting. Amazement was expressed that a person living in the age of information, of security numbers and of surveillance cameras, could remain un-named for so long. It was more than a fortnight before people living in Bathurst, NSW recognised the person in the distributed photograph as Peter James Knight. Last year he was tried, found guilty of murder and gaoled for life.

What is fascinating about this case is that the police had in their custody no inconsiderable thing - not only a picture but the corporeal embodiment of a man - yet because they had no picture of the life, the motivation, thoughts and behaviour that led to his criminal actions they effectively had nothing. The public had a picture of a face, but no name and no story. This seems to point to an important conclusion: to identify means to name.

The visual depiction of a face is not sufficient to make a picture a portrait. Douglas Watson's The hat, for example, is not strictly a portrait although it has a face in it. The title alone diverts us from thinking about it as a portrait. Similarly Watson's Nude on a bed is not strictly a portrait, for the model has her eyes modestly trained on a piece of paper - she is enclosed in a world of her own. This is a more natural effect than the nineteenth-century expedient, sometimes taken in life classes, of covering the head to ensure that the identity of the nude model was not revealed. An extreme case is afforded in a drawing by the great American painter Thomas Eakins, probably made in a life class in Philadelphia in the early 1860s. In his book on Eakins, John Wilmerding observes that 'The masked head ... is arresting ... it confounds the viewer by blanking out an area that would normally be expressively modelled. As Kenneth Clark has written ... "how determinant in any conception of the nude body is the character of the head that surmounts it. We look first at the face. It is through facial expression that every intimacy begins".

A great deal of art of the past three decades opposes the notion that any true intimacy, any understanding of character can be found in the face. In the photographs of the German photographer Thomas Ruff, we are confronted with an overwhelming physiognomic landscape of great detail. Yet the power of Ruff's portraits seems to lie in the realisation that the more we are told the less we really know about the people whose faces are represented. He insists that as a photographer he is showing us only the surface of things. Ruff's images, printed on a very large scale, gain power though static monumentality. Would animation render them any more knowable? This question was first posed - and answered in the negative - by Andy Warhol in his so-called Screen Tests of 1964-6, which presented faces filmed in two minute bites of time. Another contemporary German photographer, Thomas Struth, has recently made Video Portraits - huge projected faces presented as realtime portraits over the course of an hour. There is a terrifically mesmerising effect staring at Struth's subjects staring back at us, with the occasional flicker of movement in the face, or the wind lifting a lock of hair. The work of the British artist Gillian Wearing takes the idea of what we can know about another person a step further. In her video piece helpfully entitled Confess all on video. Don't worry, you'll be in disguise. Intrigued? Call Gillian, subjects talk about the most intimate details of their lives and histories, yet they are hidden behind wigs and masks. It is an inversion of the idea that a portrait can reveal the person. Even the greatest of contemporary figurative painters, Lucian Freud, an artist working in traditions stretching back to antiquity, views portraiture in a highly paradoxical way. The painter has described his ambition to paint the head dispassionately, as if it were just another limb. Yet recently I was intrigued to read Freud quoted as saying 'I think a great portrait has to do with the way it is approached ... it's to do with the feeling of individuality and the intensity of regard and the focus on the specific'. We can perhaps see this very different kind of engagement in Freud's great pictures of the singular Australian performance artist Leigh Bowery.

Each of the pictures I have been discussing seems to question what we can learn from looking at a picture of another person. This is a fundamental aspect of the question I am frequently asked – 'what makes a great portrait?' My usual reply has been along the lines that a good portrait is one that tells us something about the sitter, something valuable or revealing, and that creates a vivid impression of a person. But is a good portrait one that is produced by an artist who empathises with the subject? The answer is: not necessarily.

In a short story by Henry James, The Liar, James invents a character, Colonel Capadose, who is a constant teller of lies. He is tolerated, up to a point, by his society and his loyal wife seems blind to her husband's great character flaw. The story is told from the angle of a painter who is commissioned by the wife to paint a portrait of this man. Through various circumstances the painter overhears the altercation of the subject and the wife when she sets eyes on the painting for the first time. She bursts into tears, crying 'It's all there - it's all there!' 'Hang it, what's all there?' replies her obtuse husband:

'Everything there oughtn't to be – everything he has seen – it's too dreadful!'

'Everything he has seen? Why, ain't I a good-looking fellow? He has made me rather handsome.' Mrs Capadose had sprung up again; she had darted another glance at the painted betrayal. 'Handsome? Hideous, hideous! Not that -never, never!'

'Not what, in heaven's name? the Colonel almost shouted.

'What he has made of you – what you know! He knows – he has seen. Everyone will know, everyone will see. Fancy that thing in the Academy!'

'You're going wild, darling; but if you hate it so it needn't go.'

'Oh, he'll send it – it's so good!'

'It's so good?' the poor man cried.

The portrait painter asked to paint the liar achieved, all too successfully, that elusive quality of psychological penetration. His portrait captures a terrible truth.

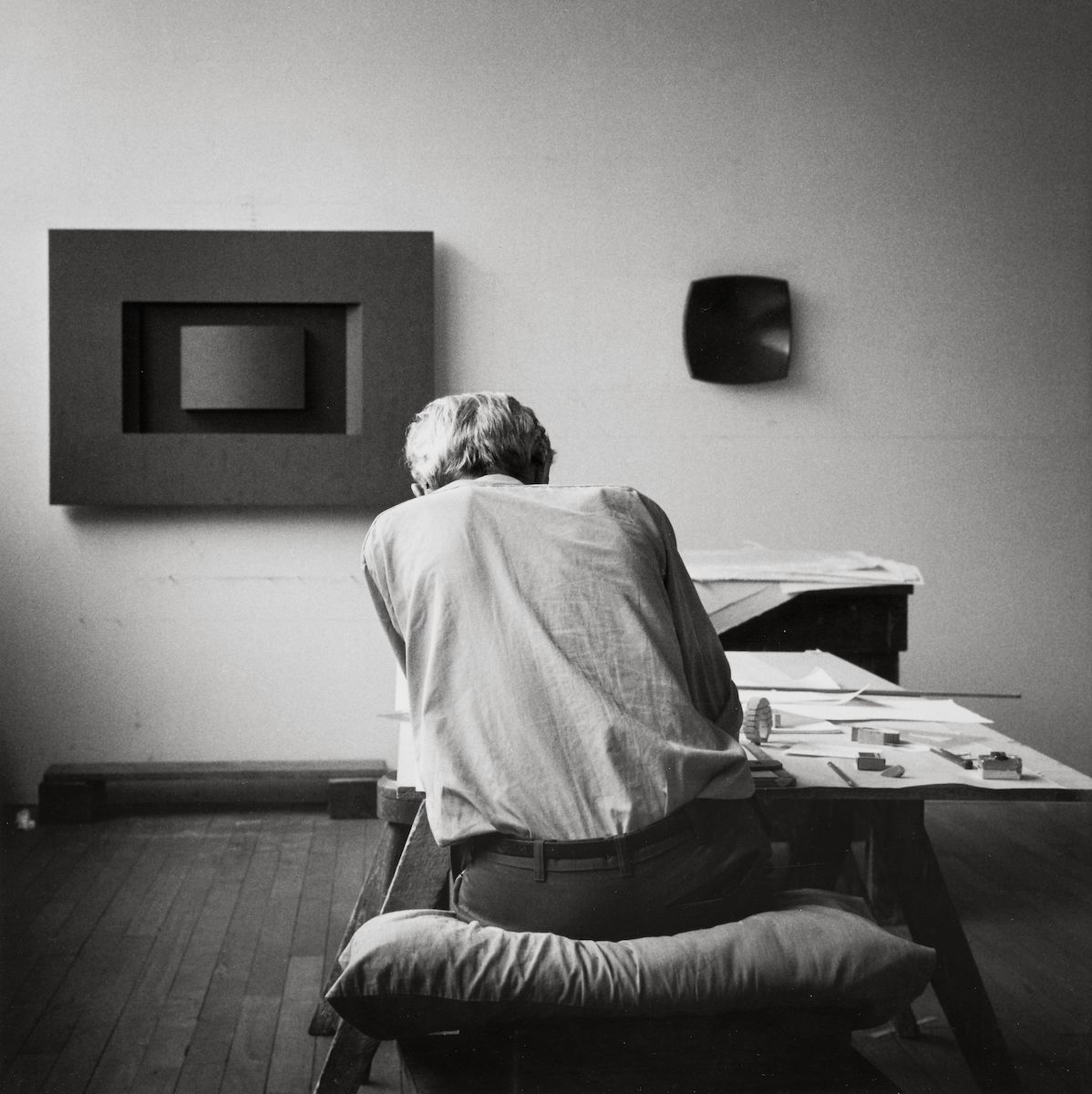

The one area where we can, I think, reliably expect to find psychological penetration is in that fascinating branch of portraiture, the self-portrait. Undoubtedly, the most orginal practitioner of the self-portrait in Australia has been Mike Parr, whose three-decade body of work has accumulated as a vast and complex self-portrait project. The self in Mike Parr's work is not a represented persona or indeed a manufactured persona, but a kind of surface on which the artist acts out a monologue about the nature of representation. The most recent chapter of his work is a series of black and white photographs, blown up to life size, of all the contents in his wardrobe.

Fundamental to Mike Parr's art is the relationship between photography and other forms of visual representation - printmaking and drawing, performance and film. Parr has elaborated frequently on the idea of 'photodeath' - the concept that a photograph, mechanically freezing a single point in time and space, is, within the realm of representation, a kind of death. We have all had the experience of looking at photographs of ourselves or of other people that we do not like because they do not conform to the relatively static image we have of faces. Curiously, it is possible for a photograph to create pictures of faces that are not likenesses at all. Of his portrait of the actress Carolyn Anspacher, taken in the early 1930s, the veteran American photographer Ansel Adams wrote 'I was impressed with the results, but many were not. It was called the great stone face and was thought by some to be a picture of a sculptured head. This actually pleased me because at the time I had a strong conviction that the most effective photographic portrait is one that reveals the basic character of the subject in a state of repose... A painter can synthesize many impressions, observations and reactions - creating a single expressive complex. The portrait photographer has only one passage of time (long or short) in which the delineation of the face is defined'. Adams, a purist in many things, described his photograph of Georgia O'Keefe and Orville Cox together as not a portrait, but 'a rewarding record of a valued moment and engaging personalities'. Although the photographed portrait can do many things that portraits in other mediums cannot, this phrase of Adams's seems to me in fact to sum up the supreme value of photography as a medium of portraiture.

Irrespective of medium or approach, likeness is an essential characteristic of a good portrait. By likeness I do not mean complete fidelity to the physical aspects of a face, but rather a more complex and more profound idea. Two definitions of likeness have been most helpful to me in thinking about portraits. An essay of 1970, 'The Mask and the Face: The perception of physiognomic likeness in life and art' by the late art historian EH Gombrich remains one of the most lucid and stimulating short pieces on the subject of the portrait. Examining caricature, photography and painting, it concludes that the most powerful portraits are those that present faces 'never arrested in one pose but wherein we experience a variety of readings, each of them coherent and convincing'. I think this idea of a living presence is much more helpful than the common notion that 'psychological penetration' is a characteristic of a good portrait. John Berger's concept of likeness, presented in his collection of essays of 2001. The shape of a pocket, is more poetic than Gombrich's yet depends equally on the idea of animation, of life, of vitality. He writes to talk of likeness is another way of talking of presence. With photos the question of likeness is incidental. It's merely a question of choosing the likeness you prefer. With a painted or drawn portrait likeness is fundamental; if it's not there, there's an absence, a gaping absence'.

Berger believes we can tell whether a likeness is there or not even when we have never set eyes on the model or seen any other image of the model. In Raphael's portrait of a woman, known as La Donna Muta ('the dumb one') he finds an astonishing likeness, concluding 'you can hear it. Clearly such an idea of likeness can not be easily attributed to fidelity to the physiognomy of a person. It is the good portrait's ability to go beyond likeness to presence - to reach to affect us across time - that makes portrait galleries and portrait prizes hugely popular; and it is the anticipation and pleasure of chancing upon such presence that has made portraiture so deeply engaging a subject for me in the years since 1998.

This is redacted version of the Nuala O'Flaherty Memorial Lecture, given by Andrew Sayers in Launceston, Tasmania in June 2004, accompanied by more than 50 slide images of portraits from around the world.