A portrait painter has complete control over what is recorded and how. A face can be constructed over years if necessary, moods suggested and backgrounds invented or simply ignored.

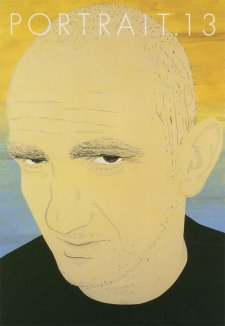

The traditional photographer has no such freedoms. The worlds of portrait painting and portrait photography were brought together in 1968 when painter Clifton Pugh and photographer Mark Strizic published side by side their respective images of significant Australians in a book Involvement: The Portraits of Clifton Pugh & Mark Strizic, edited by Andrew Grimwade. Viewed from a distance of nearly forty years, Involvement with its leather cover and expensive production values seems like a most courageous publishing venture, one that would not be contemplated in these market orientated times. Clifton Pugh is remembered as a gifted portrait painter. However, Mark Strizic's portrait photographs have not received close attention.

Strizic was born in Berlin in 1928 and arrived in Australia via Croatia in 1950. His early interests were in painting and science, but in 1957 he took up photography as a career. His talent was so pronounced that only 10 years later he exhibited a collection of photographic portraits titled Some Australian Personalities at the National Gallery of Victoria. The first photographic artist to be given a solo exhibition at the NGV, he was also the first photographer to be acquired by the fledgling National Gallery of Australia, at the first acquisitions meeting in Melbourne in March 1973.

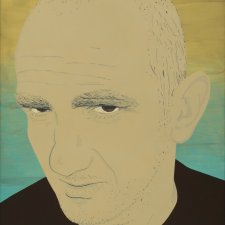

Eric Westbrook, then Director of the National Gallery of Victoria, described Strizic's effort to reveal something of the personality of his portrait sitters in a catalogue essay for Some Australian Personalities. 'Behind his camera,' he wrote, 'the artist has his own set of problems which are peculiar to the medium he employs. He accepts that he is the poet of the fleeting moment, but at the same time he must make an image which is built upon tonal appearance of the object presented to the lens and then penetrate beyond this to some permanent truth behind the moment ... the photographer juggles with time and technique in an artificial atmosphere which only his inventiveness and strength of character, together with the co-operation of the sitter, can overcome.' Strizic uses the range of available photographic tools to his creative advantage in his portrait work. Light, time, the moment, are all critical; as Westbrook writes, his camera 'both lovingly caresses and sharply defines a form and he is happiest when he restricts his tonal range to the close greys of the pencil.' However, the most notable stylistic device is his choice of the depth of field in his focus. He has said himself that 'differential focus method is the inalienable tool of photography and I use it to weld the sitter into the environment of the sitter's making and so reinforce the personality ... In the deliberate choice of differentiating the object by varying the focus and aperture, the centre ofinterest is pulled to the sitter - to make the environment vague and the sitter prominent.'

Strizic has had a lifelong interest in art and architecture and his portrait work reveals his close associations with leading figures from both professions. In 2003 the National Portrait Gallery purchased a number of vintage prints from Strizic, including portraits of architect Robin Boyd and sculptors Norma Redpath and Inge King. Robin Boyd collaborated with Strizic on the book Living in Australia, first published in 1970. In a special issue of the magazine Architecture in Australia commemorating Boyd in April 1973 Strizic described working on the book as 'the nicest project I ever had'. Boyd was 'completely open to suggestion; had an enormous grasp of compromise; and a vast knowledge and fine feeling of form ... [he] was an extremely unassuming man,' he said. His portrait of Boyd seems to give an indication of the architect's reputation as a very private individual.

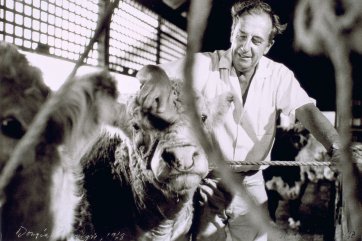

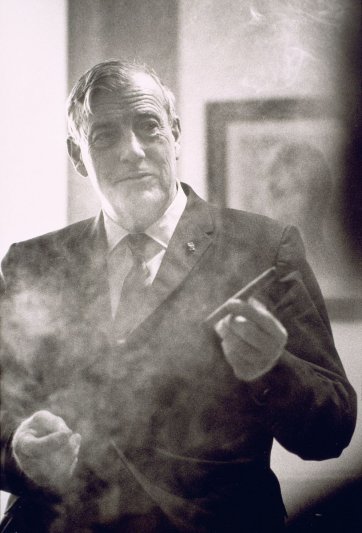

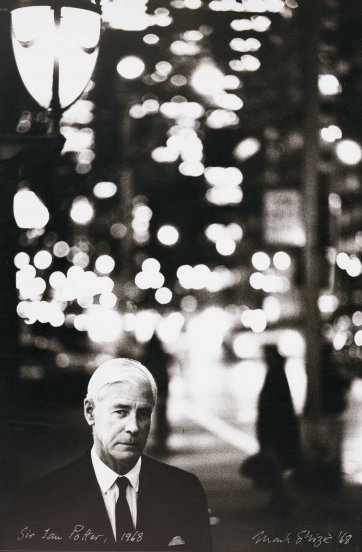

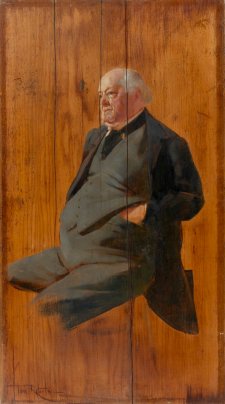

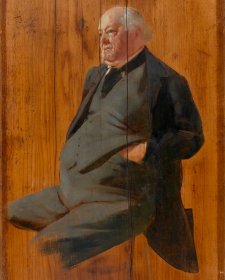

Of another work acquired by the National Portrait Gallery in 2003, a portrait of ABC managing director Sir Charles Moses, Strizic recalls that 'at the end of an unsuccessful shooting session which lasted over two hours, I finally took the photograph which is reproduced here. It is very true to the atmosphere in which we spent the whole time. He is a happy and gregarious fellow, a connoisseur and collector of many fine things, among them wines and cigars which we profusely sampled.' His evocative photograph of philanthropist Sir Ian Potter was taken under quite different circumstances. 'I had three sessions with him in New York. I had a definite idea to photograph him in the streets of New York at twilight when all the lights were coming on. I wanted to illustrate an Australian financier in the world's financial centre. To do this I had tried photographing him against skyscrapers in the day time but this was unsuccessful and very prosaic. I photographed him sitting in his chair in his own room - a powerful man who rules the financial world - but that's been done so many times that I gave up. Finally I did what I had originally intended to do ... From a previous visit I knew the atmosphere of twilight in Park Avenue was fantastic. In the final photograph the Pan Am building is there in the background and, instead of lights of the city one sees glorious silver dollars falling from the sky.'

Viewed as a body of work, Mark Strizic's portraits still carry what Westbrook called a 'lyrical linear quality which places him among the "draughtsmen" of photography.' A broad selection can be seen in Mark Strizic: A Journey in Photography, a retrospective exhibition organised by Monash Gallery of Art which showcases 50 years of Mark Strizic's work across a wide range of photographic fields including urban, industrial, commercial, and architectural photography. Living in regional Victoria, Mark continues to embrace developments in digital photography and engages in his love of painting. '