Henri Cartier-Bresson was born in Chantaloup outside Paris on August 22,1908. the oldest of five children in an affluent textile manufacturing family. However, the family's extreme frugality left the small boy believing he was poor. Completing a classic French Catholic education, Cartier-Bresson moved to Britain to study English literature and art at Cambridge University.

After compulsory service in the French Army in 1930, a desire for adventure saw Cartier-Bresson travel to West Africa on a hunting expedition where the young Frenchman took his first tentative photographs, with a Box Brownie. He would also contract blackwater fever, almost dying from the disease.

Recovering in Marseille in 1931. Cartier-Bresson acquired his first Leica - a small, quiet camera capable of making sharp pictures under difficult conditions. Owning a Leica began a lifelong search for what he coined the 'decisive moment' - a supremely spontaneous image that witnessed life unfolding with precision and emotion. Photography was a task, Cartier-Bresson said, that required virtues he had discovered while hunting in Africa - 'a velvet hand (and) a hawk's eye'.

He described the instant of taking a photograph as 'the simultaneous recognition in a fraction of a second of the significance of an event, as well as the precise organisation of forms that give (that) event its proper expression'. This philosophy has been deeply influential among Australian photographers such as David Potts, Marco Bok and the late David Moore, who once confessed to me 'Cartier-Bresson's high standards had made life difficult for all photographers'.

From his earliest photographs, Cartier-Bresson captured life in flight, sometimes literally In perhaps his most famous picture, Behind the Gare St Lazare, Pahs 1932 a man leaps to the right, taking off from a wooden ladder lying in a shallow puddle near curved metallic debris. Cartier-Bresson's reflexes are so precise his Leica's shutter records the leap at the exact moment before the man's right heel descends to the mirror-like surface of the water.

It is a moment pregnant with possibilities and as if to add visual value, Cartier-Bresson's camera records a poster in the background showing a dancer leaping in the opposing direction. This was an image that announced to photographers everywhere a new way of seeing had arrived.

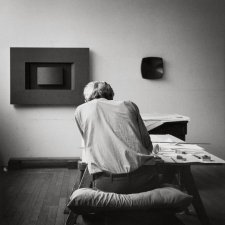

During the Second World War, Cartier-Bresson saw service with the French army's film and photo unit before being captured by the German Army in 1940. The Frenchman spent three years in prisoner of war camps before escaping on his third attempt. While on the run, Cartier-Bresson visited the artist Henn Matisse in the south of France, and made perhaps his greatest photographic portrait This image shows the bedridden painter, white dove in hand, performing his daily ritual of drawing. The irony of a dove being released from its cage was surely not lost on the fleeing Frenchman.

Apart from the phenomenal body of work Cartier-Bresson had already produced in the 1930s, his co-founding of Magnum Photos in 1947, with photographers Robert Capa and George Rodger, proved revolutionary. Forming a co-operative, they announced to magazine clients that from now on, photographers owned copyright for their pictures. Previously, they effectively had no rights to their work after publication. As Russell Miller states in Magnum, his 1999 history of the legendary photo agency, 'Capa and his friends (Cartier-Bresson and Rodger) invented copyright for photography'.

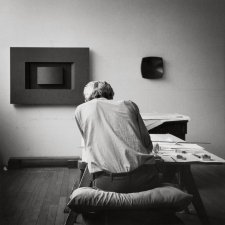

Perhaps the core of Cartier-Bresson's genius lies in his acceptance of subjects as he found them. There was never the sense that making a fine photograph was his first ambition. It was enough for him to respond, simply and deeply with heart, mind and finally, his Leica. The great photographs followed.