Over the past five years the National Portrait Gallery's Permanent Collection has been greatly enhanced through the generosity of donors who gift works into the collection. One of the latest gifts is a selfportrait in the form of a wood engraving on paper by Sir Lionel Lindsay (1874-1961).

Lindsay has been described as a painter, graphic artist, writer and critic. He is considered to be one of the most influential voices in Australian art and cultural circles in the 20th century, and in 1941 he received a knighthood for his achievements in art. Lindsay can be characterised as a Late Romantic, as he was a supporter of the conservative landscape tradition and opposed to modernist art and ideas. In his book Addled Art (1943), which has since been condemned as anti-modernist and anti-Semitic, he described the movement as the 'the cult of ugliness'.

He first worked as a pupil assistant at the Melbourne Observatory before becoming an illustrator at the Hawk and completing his studies at the National Gallery School in Melbourne. Between 1902 and 1934, Lindsay visited Spain on four separate occasions, and he regarded these trips as the most influential events on his art. His exhibition in Spain in 1927 was an amazing success, which established his international reputation as a print maker.

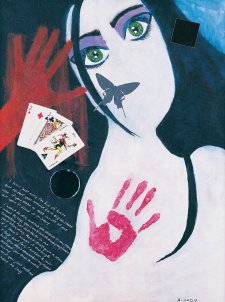

This self-portrait was made when the artist was 49 years old. Lindsay titled it The jester, fashioning himself as a comedic figure and the speaker of truth. Interestingly, his autobiography, published in 1966 was titled A Comedy of Life. The titles afford a personal, but ambiguous insight into Lionel's own self image as a joker, a comedian, which is at odds with his public persona.

The jester, a wood engraving, presents a small but precise image of the artist as a laughing, clown like figure. His dark clothing contrasts with a light mid section enhancing the face, the detail of which has been achieved with small lines and dots in the cheeks and around the eyes, and cross hatching in the teeth. The whole image is beautifully toned and presents an excellent example of Lionel's favourite medium, wood engraving.

Wood engraving is a printmaking technique first developed in England in the late 18th Century. Although both wood cuts and wood engravings are relief types of printing, wood engraving, or 'white line engraving' differs from woodcuts in the tools that are used, the types of wood used and the line of the grain within the wood. Wood engraving employs hard woods, which are carved into the end-grain and uses tools such as a graver and a burin rather than knives. Designs are incised into a wooden block and then printed. The lines print white on a black background. The effect produced is a finer, more delicate line and the technique is considered to be easier than wood cutting.

This self-portrait by Sir Lionel Lindsay is a multi layered gift. On one hand it adds to the National Portrait Gallery's rich collection of self portraits by significant Australian artists; Lionel Lindsay has been praised as one of Australia's finest black and white artists, a fine etcher, woodblock and a dry point printer. On the other hand, Lindsay's family history and connections are part of one of the most interesting artistic families in Australia's art history.

There were 10 children in the Lindsay family and five of them became well known. Largely self-taught artists, each contributed something unique to the Australia arts. Percy (1970-1952), the eldest brother, who has been described as one of Australia's best colourists, painted landscapes around the Heidelberg district. He was followed by Lionel (1874-1961) and then the best known Lindsay, Norman (1789-1969). Ruby (1887-1919) and Daryl (1899-1976) came later and were also known for their fine drawing and printmaking skills. Ruby, who was married to Will Dyson, did not get to live the same long and successful life as her brothers, dying at only 32 from Spanish Influenza. In her short life, she did however contribute substantially to the graphic arts, producing a large body of work, consisting mainly of illustrations for magazines, poems, short stories and posters.

Collectively the Lindsays witnessed many changes in Australian culture, starting with Federation in 1901, through two World Wars and the Depression. Images relating specifically to Australian events and culture can be seen in all the Lindsays's work. Coming from Creswick near Ballarat, Victoria, the family was at home in rural Australia. With the arrival of Federation producing what has been described by Colin Holden as an "upsurge of Australian nationalism and a mythology centered on the bush", common themes running through all of the Lindsays's works were the Australian landscape and the people who inhabited it. Both Norman and Lionel worked for the Bulletin, the immensely popular and influential weekly magazine whose regular contributors also included the poet A. B.'Banjo' Patterson, Henry Lawson, George Lambert and Miles Franklin. Lionel also produced illustrations for Steele Rudd's Dad and Dave stories, images of Cobb and Co and a portrait of Henry Lawson, both of which were turned into postage stamps.

Together the Lindsays were a family who influenced and promoted the Australian arts. This is evident in their involvement in the establishment of artists' societies, galleries and collections of works. Lionel Lindsay established the Australian Painters-Etchers' society, of which he was president for three years. Norman's and Lionel's work for various newspapers contributed greatly to the rise of graphic illustration in Australia, as did Ruby's. Lionel, Norman and Percy were regular exhibitors at the Society of Artists, and Darryl was appointed Director of the National Gallery of Victoria in 1942.

Although Norman and Lionel were very close in their younger years, they had a major falling out around 1917 and in the end correspondence was strained. The nature of their quarrel stems from a few different accounts and issues. In 1930 Norman wrote his book Redheap, which was banned in Australia until 1958. In the book Norman created 'fictional' characters that were closely based on family members and friends. Norman based his character 'Robert' in Redheap on Lionel, who was not happy about how this character was portrayed. Another source of tension was Norman's spirituality and his belief in the afterlife, of which Lionel thoroughly disapproved. Lionel's success overseas may also have contributed to the stiffness between the brothers.

The National Portrait Gallery Permanent Collection holds two other portraits of members of this family; a photograph of Norman Lindsay by Max Dupain (1936), also a gift into the collection, and a photograph of Norman's wife, muse and model, Rose Lindsay by Anthony Browell (1970).

The jesteralong with eighty other selfportraits by Australian artists is on show until September 19 as part of the National Portrait Gallery's temporary exhibition To Look Within: Self Portraits in Australia.

The extensive research conducted by Joanna Mendelssohn on Sir Lionel Lindsay and the Lindsay family has been invaluable in the writing this article. I encourage any one interested in the Lindsay family to read both Letters and Liars and Lionel Lindsay an artist and his family.