On Friday, 20 March 2020, the front page of the Hobart Mercury featured little other than a satellite image of Tasmania and a pugnacious headline: ‘We’ve got a moat and we’re not afraid to use it’. Tasmania’s ports closed at midnight that day as the state acted to maximise its natural self-isolation as protection from the coronavirus cases multiplying on the mainland. 20 March 2020 was also the day I returned to so-called civilisation after a week-long bushwalk in one of the island’s fabled national parks. My trip back to Canberra suspended; my workplace facing imminent, indefinite closure; the strong temptation to head straight back out into the bush resisted; what else to do but settle in and gear up for an extended, unexpected stay?

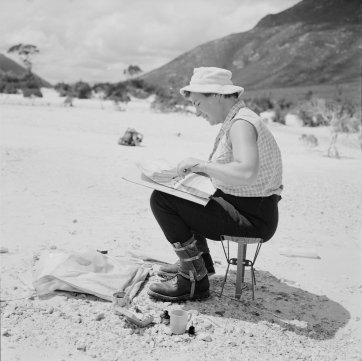

First things first: reading matter. Unsurprisingly, given the several days of walking and camping in breathtakingly splendid country – tea-coloured tarns; deep, majestic forests; glowering dolerite bluffs and peaks – the first books selected for my lockdown reading list included several about Tasmania’s World Heritage-listed wilderness areas, and others by or about people who best embody the philosophy of truly being in them and the pleasure of returning again and again to the same place. The preeminent environmental campaigner and former Greens leader Bob Brown, for instance; watercolourist Max Angus; engineer and photographer Ralph Hope-Johnstone; artist and educator Elspeth Vaughan; and Olegas Truchanas, whose ineffably lovely images of the now-submerged Lake Pedder provide a melancholic essay on the unfathomable foolishness of those who made the disastrous decision to destroy it.

At the same time, these artists and writers created rich and enduring proof of the necessity of quietude, the virtues of staying close to home, and the depth of solace and sustenance one might find in untouched environments. All found refuge and inspiration in wild places, experiencing them either solo or in select company, and with the clarity that only a pursuit like bushwalking in remote, sometimes challenging territory affords. Perseverance, self-reliance, limbs, lungs, senses, an appreciation of simple things – the cup of tea at lunchtime, good boots, dry socks and a down sleeping bag. ‘This vanishing world’, Truchanas said in 1971, ‘contains in itself rewards and gratification never found in the artificial landscape, or man-made objects so often regarded as exciting evidence of a new world in the making. … The natural world contains an unbelievable diversity, and offers variety of choices, provided of course that we retain some of this world, and that we live in the manner that permits us to go out, seek it, find it, and make those choices.’ What better model then for how to make meaning of simplicity and isolation at this juncture, as countless numbers bemoan restrictions on crowded, clamorous pastimes and places, and when solitude is being sold, even more than usual, as negative, damaging and undesirable?

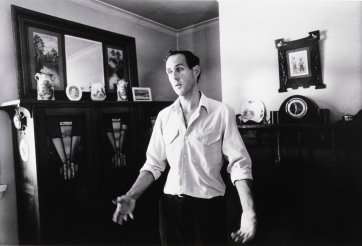

Whereas the various schemes of the 1970s and early 1980s to dam the Franklin and Gordon Rivers garnered widespread resistance – and were ultimately thwarted – the earlier fight to avert the inundation of Lake Pedder was lost despite the advocacy of activists, including the now legendary cohort of artist-bushwalkers who’d been documenting the Tasmanian south-west since the late 1940s, and who were the first to help the rest of us see and appreciate its peerless power and beauty. Arguably the most enigmatic or legendary of them was Olegas Truchanas. Born in Lithuania in 1923, Truchanas arrived in Australia as a displaced person in the late 1940s, having fled the Russian and German invasions of his homeland during the war. After spending some time at the Bonegilla Migrant Reception Centre in Victoria, Truchanas settled in Tasmania. He undertook his compulsory two years of labour at the Electrolytic Zinc Company’s works on the Derwent River, joined the Tasmanian Miniature Camera Club, and began exploring Hobart and its environs on foot, on skis and by boat, often – even preferably – on his own. ‘Where other migrants gained strength from gathering into a community,’ his widow Melva Truchanas recalled in 2011, ‘he was happily off up a mountain somewhere’. Max Angus, who edited the 1975 monograph The World of Olegas Truchanas, similarly recalled him as a loner, an ‘inside’ man: ‘he wasn’t a self-promoting or big “I am” man at all. He quietly stole into your mind.’ Among his notable undertakings were a solo climb of Federation Peak – an awesomely precipitous quartzite monolith at the south-eastern end of the Arthur Range – in 1952; and the first known journey down the Serpentine and Gordon Rivers from Lake Pedder to Strahan on the west coast – an epic solo paddle Truchanas accomplished in a kayak he designed and built himself.

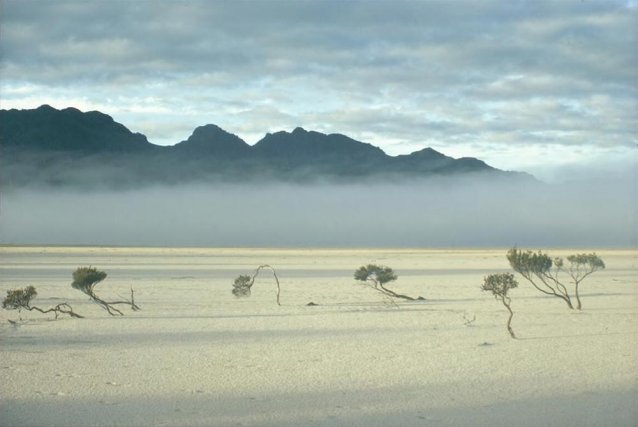

Truchanas recorded these and his many other journeys in photographs that he began showing in the 1950s to illustrate his public lectures – photographs by which, as his biographer Natasha Cica has said, he ‘subtly but surely crafted the modern frame through which we now interpret the beauty and value of Tasmania’s wild places’. His output – or rather, the output of the five years following the loss of his home and photographic archive in the bushfires that decimated areas of southern Tasmania in 1967 – includes bracing, expansive views of the astonishing ranges, peaks and gorges situated in what are now the Franklin-Gordon Wild Rivers, Mount Field and Southwest National Parks, along with intimate details of snow, clouds, shadows and reflections, and studies of plants and seasons.

Truchanas’ landscapes have something of Romanticism about them and amply demonstrate the sensibility he acquired from his study of photography in Germany and its application in the alpine environments he traversed there. Other pictures are perfectly still, soothing and quiet. As Angus observed, ‘travelling alone in the South-West made it possible for him to pause for an hour or two, to allow a shadow to lengthen, mists to rise, or some eminence to emerge into light. He knew, like most artists, that silence and meditation are the true sources of revelation: his photographs confirm it.’ Spines of mountain ranges emerge from mists; fronds and branches reach out from beneath thick snow; waves of rain wash in from the west; rugged vistas are precisely mirrored in pristine surfaces of water.

In the early 1960s, when Tasmania’s Hydro Electric Commission and Premier ‘Electric Eric’ Reece controversially announced a plan to dam the rivers of south-west Tasmania, and – despite its national park status – flood Lake Pedder, Truchanas began to employ his photographs not just to demonstrate the rarity and significance of the south-west, but as a potent means of mobilising support for its preservation. ‘In the days before television, the internet, glossy wilderness calendars and mainstream environmental concern, the majestic beauty of the south-west literally was unseen, even by most Tasmanians’, Cica explains.

As an employee of the Hydro Electric Commission himself, Truchanas knew his advocacy came with considerable personal risk. Assisted by his HEC colleague Hope-Johnstone – whom Elspeth Vaughan later married – and by the young photographer Peter Dombrovskis, Truchanas presented a series of luminous, large-scale slideshows of his work so as to awaken locals not just to the presence of such extraordinary landscapes but to the absolute necessity of keeping them intact. ‘When Pedder was threatened’, Vaughan recalled, ‘Olegas brought his lecture slides to Ralph one morning, put them on his desk and said, “I booked the town hall – I want to make these into an audiovisual and we will show it”’. Hope-Johnstone devised a lighting and projection method that enabled the pictures to fade in and out in concert with music and Truchanas’ voiceover. The photographer ‘knew Lake Pedder intimately’, Angus explained. Specifically ‘he knew that no map, no description, however detailed, could remotely convey the sense of awe and wonder felt by those who saw this place. … It is like another language, beyond the reach of maps or words.’ One of the presentations sold out the Hobart Town Hall eight times in mid-1971 and subsequently captivated audiences in venues on the mainland. Truchanas’ photographs were exhibited alongside images of Pedder made by Vaughan and fellow watercolourists including Angus, Patricia Giles and Harry Buckie in a show that was launched at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery later the same year.

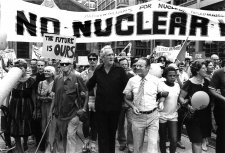

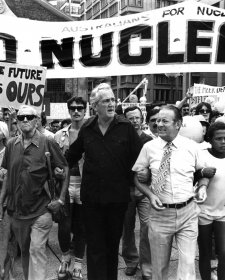

By this time, however, the flood waters that would subsequently bury Lake Pedder had already started building, and the efforts of neither environmentalists, artists or political leaders would make a difference. In late 1971, after spending the Christmas break camping at Lake Pedder and in anticipation of the next, imminent threat to the wild rivers of the south-west, Truchanas prepared for another solo canoe trip along the Gordon, during which he intended to start retaking some of the hundreds of slides lost in the 1967 fire. He drowned in the Gordon in January 1972. Later that year, the world's first 'green' political party was formed in Tasmania. Bob Brown, one of its founding members, subsequently led the bitter and protracted but ultimately triumphant fight to spare the Franklin River from Lake Pedder’s fate. Brown is now integral to the committee which is seeking to reverse the damage to Lake Pedder in time for the 50th anniversary of its loss.

Related people

Related information

Staying home

True south #2

About Face article14 July 2020

Joanna Gilmour brings a mindful Douglas Mawson’s perspective to bear on the concept of isolation.

The activist A-list

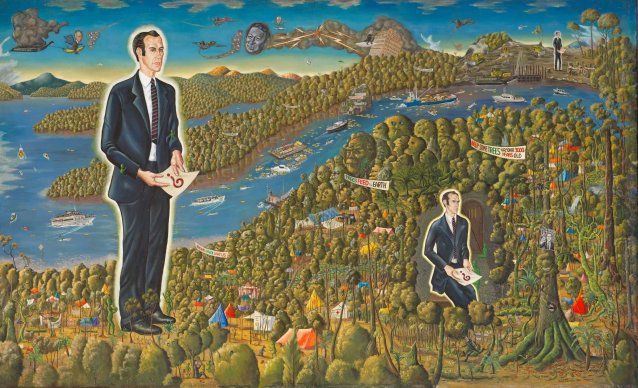

Magazine article by Dr Sarah Engledow, 2007Dr Sarah Engledow examines a number of figures in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery who were pioneers or substantial supporters of the seminal Australian environmental campaigns of the early 1970s and 1980s.

Written in Water

Magazine article by Dr Sarah Engledow, 2005Olegas Truchanas and Peter Dombrovskis, photographers and conservationists, shared a love of photography and exploring wilderness areas of Tasmania.