It’s been several months now that I’ve spent my working days at the table in a cabin on my brother’s property in southern Tasmania. I’ve watched autumn become winter from this spot. The vineyards down the road have gone from rudely green to utterly denuded. Dishevelled yellow leaves cling here and there to the spindly naked limbs of fruit trees, while kunanyi/Mount Wellington and the peaks around it are more likely now to be seen crusted with snow. Light diminishes rapidly as of four each afternoon and the animals in neighbouring paddocks graze on frosty grass in the mornings. All the while, the radio has descanted constantly, mostly forebodingly, on ‘these challenging times’ and the message on a continuous loop along the top of my phone has exhorted me to #StayHome.

Suits me. If there are such things as individuals purpose-built for self-isolation, I’m one of them, and were it not for this pandemic having occasioned the loss of lives, livelihoods and loved ones, I wouldn’t object to the repetition of situations that make us rethink our definition of ‘essential’. I know some would shudder at this suggestion, that various implications of the past few months are grave and far-reaching, and that for many it’s anathema to remain in the same place and keep the same company – the children who should be at school; the pets discomfited by the sudden advent of working-from-home; the supposed soulmate who, it turns out, really gets on our nerves. It seems that in a society that has come to consider me-time and macchiatos a birthright, many have lost the ability, or the imagination, to embrace simplicity, sameness and stillness. Indeed, it seems to have taken a global public health crisis for us to relearn how to compromise, improvise and adapt, and to fully grasp the maxim that less is more.

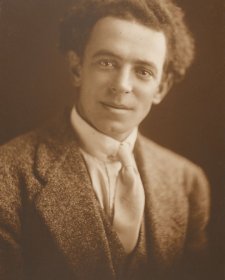

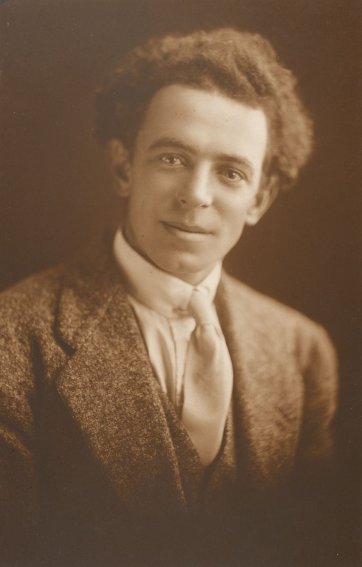

Item two in the pile of books comprising my lockdown reading list has been particularly instructive in this respect – said book being The Home of the Blizzard, Douglas Mawson’s compelling account of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE). A geologist and professor at the University of Adelaide, Mawson first went to Antarctica in 1907 as a member of Ernest Shackleton’s British Antarctic Expedition, and soon after returning began to devise his own exploratory and scientific venture on the frozen continent. After over two years of planning and fundraising, Mawson’s expedition sailed from Hobart in December 1911. Bases were established at Macquarie Island and on the Shackleton Ice Shelf, while Mawson and a team of scientists and experts stationed themselves at Cape Denison on Commonwealth Bay, which is due south of Hobart by at least 3000 kilometres.

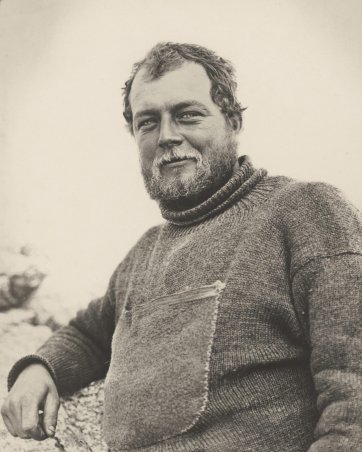

The AAE proved monumental in terms of its scientific discoveries and geographical claims, but is arguably better known for the extremes of endurance, commitment and fortitude it exacted from its men, especially Mawson – the only survivor of a tragic sortie across an unexplored stretch of Antarctic territory in the summer of 1912–1913. The journey claimed the lives of the two other participants: British soldier Belgrave Ninnis, who vanished into a crevasse in December with a sledge-load of critical equipment and provisions; and Swiss mountaineer Xavier Mertz, who died in early January from malnutrition, exposure and extreme psychological stress. The trio’s huskies had all perished by this stage too. Dangerously debilitated himself, and completely alone, Mawson somehow made it the remaining 100 miles back to base but missed, by a matter of hours, the departure for home of the expedition ship Aurora. Mawson waited out another winter with the several men who’d stayed on just in case he showed up, and finally returned to Australia – and adulation – in 1914.

Don’t assume, however, that this will be yet another piece about the personal qualities evidenced by Mawson’s survival of his unimaginable ordeal – qualities like courage, resilience and others that we’re hearing a lot about of late. No. I’m thinking of what The Home of the Blizzard documents about much more prosaic things – the sort of resources even mere mortals can find if they know where to look for them. How to find contentment amidst deep, wintery discontent; how you keep yourself from going bonkers when you’ve got no choice but to #StayHome. How routine and being in the one place clarifies your attention, what it makes you notice. Books, letters, music, memories, photos, food, nature, the night sky. In its retelling of an endeavour characterised by social, geographical and psychological conditions which truly were gruelling, Mawson’s narrative is a timely reminder that even those who are outwardly so uncompromising and indomitable are capable of recalibration when required.

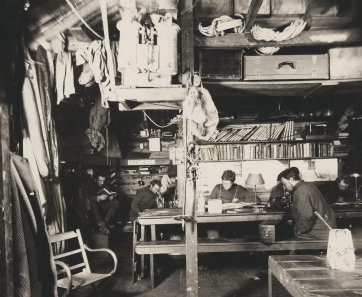

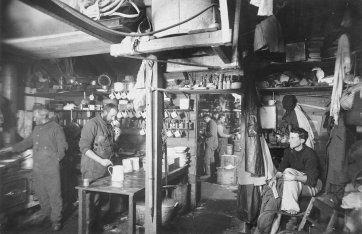

Imagine eighteen chaps, average age about 25, occupying a prefabricated timber hut, just over seven metres square and serving as a kitchen, dining room, darkroom, living room, pantry, laundry, library and storeroom as well as sleeping accommodation. A contingent of huskies, fed mainly on seal meat and blubber, occupies the passageway alongside. Remember that the chaps are unlikely to be bathing frequently, as doing so involves melting snow for bathwater. Besides, there’s bugger all privacy or ‘personal space’. Their wardrobe consists of ‘thick woollen undergarments, with outer garments of Jaeger fleece’, plus items including ‘fur mitts made of wolf skin, as well as woollen ones’ and footwear fashioned from leather and reindeer hide. Things such as sodden socks and stockings are often hung above the stove to dry, and ‘these had a habit of dripping into the tea water as they thawed, or of falling into the soup with a strong probability of imparting an undesirable bouquet of dog and blubber’. The chaps’ partiality to pipe and cigar-smoking adds to the olfactory equation.

Then factor in the hut’s location. As Mawson wrote: ‘With regard to climate in general, Antarctica has the lowest mean temperature and the highest wind velocity of any land existing’. Cape Denison, where Mawson’s Hut still stands, was possibly the coldest, windiest bit of the coldest windiest continent, and by ‘stepping out of the shelter of the Hut, one was apt to be immediately hurled at full length downwind’. ‘The strongest man, stepping on to ice or hard snow in plain leather or fur boots, would start sliding away with gradually increasing velocity; in the space of a few seconds or earlier, exchanging the vertical for the horizontal position.’ The weather could confine the chaps inside for weeks and weeks on end, Mawson noting in November 1912 that, since January, there’d been ‘but a few days of calm weather and the wind has blown with such terrific force as to completely eclipse anything previously known elsewhere in the world’.

Several men, like the meteorologist Cecil Madigan, had roles that necessitated going outside, blizzard or not; and some, like storeman Herbert Murphy, had to tunnel through snow to get to the supplies. The wireless connection to Macquarie Island and hence the mainland failed every time a mast was felled by the wind, and so for most of 1912 there was none of the anticipated communication with friends and family, and nothing at all that could traverse the thousands of kilometres of treacherous ocean between them and home. ‘I realised when I read of those days what Douglas had in mind when he said that what he looked for when choosing men for the expedition was not so much physical strength as … a man’s outlook on life’, wrote Mawson’s wife Paquita in 1964. ‘The physical part would be required as a matter of routine, but a man’s own mental resources, these are more important.’

First published in 1915, Mawson’s narrative is in part a comprehensive, chronological account of the expedition’s events and activities. But he wrote it also hoping that sales of the book might account for a portion of the expedition’s debts, and his choice of Frank Hurley as official photographer was similarly informed by an appreciation of the wit and dramatic sensibility Hurley imparted to his images. As a result, for all of its exhaustive detailing of facts – inventories, dates, temperatures, tonnages, degrees, depths and velocities – there’s a corresponding level of candour in its depiction of ordinary frailties and everyday life. The book describes the solace or stimulus to be found in daily patterns and routines; the insights and delights that coexist with danger, discomfort and hardship; and what it’s like to be unexpectedly exhilarated by a sight or a feeling that can’t be explained rationally – ‘the quickening of the pulse, the awakening of the mind, the tension of every fibre’.

Daily tasks, for instance, ‘were the elixir of life’ in the hut. Some took the shared responsibility for cooking seriously, and ‘under the inspiration of Mrs Beeton’s comprehensive work’ produced ‘puff pastry, steam puddings, jellies and blanc-manges, original potages and consommés’ as well as various concoctions incorporating seal and penguin meat. Occasional luxuries were prized for their ‘psychological effect’. The chaps also shared the role of nightwatchman, whose job included keeping the stove alight, cooking breakfast and making regular observations of the skies and the weather – although the performance of said duties saw Mawson rather gritting his teeth first thing in the morning at times: 'While others strove to collect their befuddled senses, this individual … boasted of the number of garments he had washed, expanded vigorously on bread-making – his appetising specimens in full public view – told of the latest escapade among the dogs, and spoke of the fitful gleams of the aurora between 1.30 and 2.00 am.'

Meanwhile, birthdays and other significant events, such as the winter solstice, were celebrated ‘with the uproarious delight of a community of young men unfettered by small conventions’, and prompted the creation of songs, speeches, poems and revues. Books were devoured and discussed, diaries were written, letters were read and reread, photographs were pored over. In the part of the hut known as ‘Hyde Park Corner’ they’d listen to jokes and stories told by resident raconteurs.

Addressing an assembly in Adelaide shortly before the AAE’S departure, Mawson stated that ‘in that land of desolation, in that land of loneliness to which we are about to proceed, there are conditions to measure a man at his worth.’ It’s almost as if he was asking to be remembered only for his extraordinary mind and endurance. As his great-granddaughter Emma McEwin has written, ‘Mawson has been consistently defined and confined by the public status of his polar experience, and it has somehow pared him down, simplified him; reduced him to the man who ate his husky dogs to survive; who cut his sledge in half with his pocket saw; who fell down a crevasse and hauled himself to the surface.’ This ‘one story’ of Mawson’s survival, McEwin explains, has obscured almost every other facet of his life.

In her biography of Mawson, not even Paquita was permitted to quote at length from his private Antarctic correspondence at the risk of revealing him to have been so solicitous and gentle. The hardman explorer inclined to be undone by a fine day or splendid sky. The supposed iceman who addressed his distant fiancé as ‘warm heart of mine’ and whose love letters were riven with guilt about the anxiety his calling was causing her. ‘Know Darling that in this frozen South I can always wring happiness from my heart by thinking of your splendid self’, he wrote in January 1912.

This was more than a century ago, remember. Men were men, women were emotional, and suspicion ensued when chaps – particularly heroic ones – betrayed too much of a rich and nuanced inner life. Maybe what’s been most pleasing then about reading The Home of the Blizzard again – and amidst ‘these challenging times’ – has been to see Mawson and his hutmates laid bare by the enormity of their undertaking, and to trace the hints of the ‘outlook on life’ that enabled them to navigate the tension between beauty and danger, sensation and oblivion, self and obligation. ‘The vast, solitary snow-land cold-white under the sparkling star gems; lustrous in the rays of the southern lights; furrowed beneath the sweep of the wind’, Mawson wrote. ‘We had come to probe its mystery, we had hoped to reduce it to terms of science, but there was always the “indefinable” which held aloof, yet riveted our souls.’

Related information

Giving a dam

True south #1

About Face article22 May 2020

Ensconced and meditative in crisp Tasmania, Joanna Gilmour pays tribute to passionate green advocate and photographer Olegas Truchanas.

Of ice and men

Magazine article by Joanna Gilmour, 2009Frank Hurley's celebrated images document the heroism and minutiae of Australian exploration in Antarctica.

The Gallery

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!

![Lieutenant B E S Ninnis, R F, in uniform [Australasian Antarctic Expedition, 1911-1914] , c. 1913 Lieutenant B E S Ninnis, R F, in uniform [Australasian Antarctic Expedition, 1911-1914] , c. 1913](/files/f/7/2/f/i14012-th.jpg)

![The wild west coast of Macquarie Island [Australasian Antarctic Expedition, 1911-1914], c. 1913 L R Blake The wild west coast of Macquarie Island [Australasian Antarctic Expedition, 1911-1914], c. 1913 L R Blake](/files/d/a/1/e/i14013-th.jpg)