Friends Olegas Truchanas and Peter Dombrovskis, photographers and conservationists, were products of two Baltic generations uprooted in the Second World War.

Linked by the experience of immigration, and a European cultural heritage of healthful hiking, the men shared two great loves: photography, and exploring the wilderness areas of the South-West of Tasmania, to the preservation of which they were dedicated. Sadly they shared, too, the destiny of dying as they pursued their passions – Truchanas in 1972, aged 49, and Dombrovskis in 1996, when he was 51.

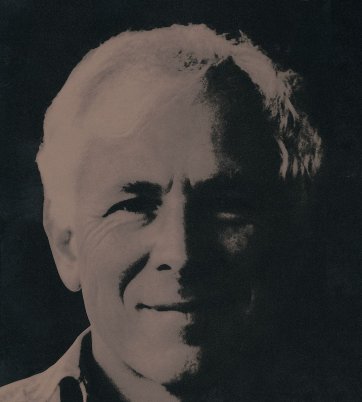

Olegas Truchanas (1923–1972) was born in Siauliai in Lithuania, a country that endured successive invasions and huge loss of life and liberty in the years before it was handed over to Russia under the Yalta agreement in 1945. At the collapse of the Lithuanian resistance movement, Truchanas fled to Germany. At the war's end he was settled in the camp for Baltic displaced persons in Garmisch. He enrolled in law at Munich University, spending his recreational hours in the Bavarian Alps, where he skied, climbed and began taking photographs. He migrated to Australia in 1948, proceeding to Tasmania from the Bonegilla migrant reception centre in Victoria and serving his required two years' public works for the Electrolytic Zinc Company in Hobart. During this time he began to explore the surrounding landscapes, joined the Southern Tasmanian Miniature Camera Club, and continued to practise the salon photography he had begun in Bavaria.

Coming from a traumatised and congested Europe, Truchanas was fascinated by the sublime geography of the South West of Tasmania, at that time mostly unexplored by the state's Anglo-European inhabitants. In 1952 he made the first solo climb of Federation Peak. Not long after, he began preparing for a trip to a hazardous, spectacular and mysterious stretch of the Gordon River known as 'The Splits'. He designed a dismountable canvas-covered canoe for the journey, but lost it, along with most of his gear and the trousers he was wearing, in a life-and-death struggle with a waterfall. In early 1958, in an improved version of his kayak, he became the first person to succeed in a solo canoe journey down the wild Serpentine and lower Gordon rivers. One of his canoes is now in the collection of the National Museum of Australia.

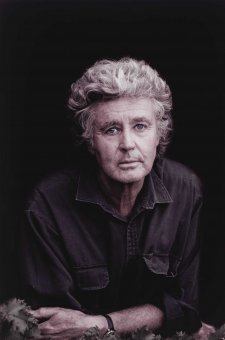

In the early 1960s, married with a young family, Truchanas became an instructor for the National Fitness Council. One of the many lads whose lives he influenced was Peter Dombrovskis (1945-1996), who had been born of Latvian parents in a refugee camp in Wiesbaden at about the time Truchanas moved to Garmisch. Dombrovskis's father disappeared as the war ended, and Peter came to Australia with his mother, Adele, when he was five. Passing through Bonegilla reception centre, they settled in Fern Tree on the slopes of Mount Wellington, and as he grew up over the 1950s they explored its vicinity together, Peter taking the 35mm Zeiss camera Adele had bought him. When he was thirteen, the pair walked the Overland Track. A couple of years later, the fatherless teenager began to build his photographic, water, snow and bushcraft skills under the guidance of Truchanas, often credited as his mentor. 'There weren't any half measures with Olegas,' he recalled. 'He was a perfectionist in everything, both in his enjoyments and his more serious pursuits ... There was a beauty about everything he did that appealed to me.'

In 1963, when Truchanas had been working for twelve years at the Hydro Electric Commission, the Commonwealth Government and Tasmanian Premier 'Electric Eric' Reese announced plans to explore the 'vast hydro-electric resources known to exist in the Gordon River area'. Over the next three years, it became clear that Lake Pedder, the jewel of the South West National Park, was to be submerged by a water storage impoundment held by the Gordon Dam. As a public servant Truchanas could not criticise the plan openly; all he could do was show Tasmanians, and the wider world, the nature of the area proposed for obliteration. He did so in a series of standing-room only audio visual presentations at the Hobart Town Hall, exhibiting photographs he had taken on more than 30 trips to the pristine regions, accompanied by a stirring soundtrack and light show devised by engineer Ralph Hope-Johnstone. Hope-Johnstone, who had taken the first colour photographs of Lake Pedder in 1947, observed that so staggering was the beauty of the lake that 'communication between those who have seen Lake Pedder and those who have not, has always been difficult and must remain so. It is like another language, beyond the reach of maps or words.'

In February 1967 Truchanas lost his house and possessions, including the photographs he had amassed over a span of fifteen years, in catastrophic fires that swept southern Tasmania. Over the few remaining years of his life he built up some 4000 new images of his beloved adopted state. In 1968 he began a successful one-man campaign to prevent the destruction of a jeopardised 408-hectare virgin Huon pine forest on the banks of the benison River in the South-West. 'Is there any reason why,' Truchanas asked in late 1971, 'given enlightened leadership, the ideal of beauty could not become an accepted goal of national policy? Is there any reason why Tasmaniashould not be more beautiful on the day we leave it, than on the day we came?' At the beginning of 1972, the year the world's first Green political party was formed in Tasmania, Truchanas died accidentally during a canoeing trip on the Gordon. His body remained undisclosed until a search party of his friends built a temporary weir in the river above where they knew he must be; as the water level dropped Peter Dombrovskis found him, entangled with a submerged tree. Truchanas's ashes were scattered over Lake Pedder, inundated later that year. The benison River Huon Pine Scenic Reserve, lying in the Wild Rivers National Park, was renamed the Truchanas Huon Pine Forest as a tribute to his pioneering contribution to environmental conservation in Tasmania.

The campaign to save Lake Pedder provided the model for the Franklin campaign, waged between 1976 and 1983 as the Tasmanian government was pressured into vacillation between various schemes to dam first the Franklin River, then the Gordon above Olga (involving the inundation of 'The Splits'), then the Gordon below Franklin. The Tasmanian Wilderness Society was formed in 1976, at a meeting at the home of general practitioner Bob Brown. As moves to dam the Franklin gathered momentum, he abandoned his practice and became the Society's full-time voluntary director. Bob Brown realised that in the fight for the Franklin 'there was no better way to get the river to speak for itself than through the lens of Peter Dombrovskis'. When legislation was passed allowing construction to begin on the Franklin dam in 1982, Brown staged a nationwide tour that saw large NO DAM rallies in capital cities. Volunteers hastened to mount blockades in Tasmania and public figures such as prehistorian DJ Mulvaney laboured to raise public consciousness of the profound cultural, historical and ecological significance of the area at stake – countering Tasmanian Premier Robin Gray's assessment of the Franklin as nothing but a brown ditch, 'leech-ridden' and 'unattractive to the majority'. Dombrovskis's photographRock Island Bend, Franklin River, South West Tasmania(1979), selected by Brown from the photographer's large collection, became the lead image of the NO DAMS campaign and one of the most-reproduced of all Australian photographs. Printed in colour above the question 'Would you vote for a party that would destroy this?' it comprised one of this country's most effective ever political advertisements. Further, in large part due to Dombrovskis's remarkable eye for detail – its composition, as Peter Timms has explained, is 'exceptional in its fidelity to European artistic and cultural precedent' - it took root in the collective European-Australian psyche to become, Timms and others believe, a kind of 'religious icon for a new, secular society'. In 1983, the High Court ruled that the Commonwealth Government had the power to prevent the dam from being built.

'When you go out there you don't get away from it all ... you come home to yourself,' Dombrovskis said. He died of heart failure while photographing alone in the Western Arthur Range in southwest Tasmania. Shortly before, he had tried to describe the need he felt, after photographing an object of beauty, 'to make some acknowledgement, a sign of gratitude, perhaps a touch or some act of private communion that would probably appear silly or affected were there someone else to see me.' He wrote that 'my most productive days are when I move through the landscape with an attitude of acceptance.' To his many admirers, the images he made are imbuedwith the photographer's respect for the natural world. Although Truchanas and Dombrovskis inspired many subsequent adventurers, conservationists and photographers, there has emerged no 'new Dombrovskis' with the required combination of technical skill, spiritual engagement and aesthetic sensibility to confront Australian voters with the reality of ongoing threats to Tasmanian forests and rivers. It is a significant point, for as Bob Brown explained, 'it was not so much that Truchanas and Dombrovskis recorded national parks, as that national parks followed where they recorded.'