When I look at the portraits and early photographs of my Robertson forebears, the first of whom arrived in Hobart 200 years ago, it is difficult to lay their early struggles to establish themselves in this harsh country against what we now understand about the true nature of the displacement of First Nations people.

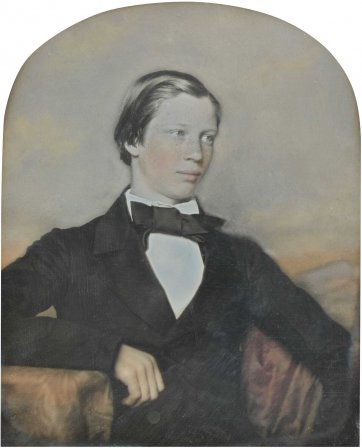

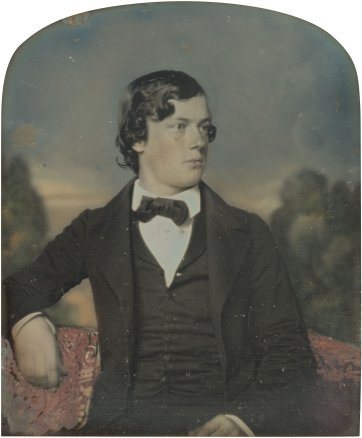

These portraits do, however, give us a glimpse into the Robertson family’s lives, social rise and art-collecting habits, which were mirrored by photography’s increasing popularity as a portrait medium at the time. A number of images, which have survived from the earliest days of photography in the 1840s, are included in the National Portrait Gallery’s new photography collection display in Gallery 7, curated by Joanna Gilmour.

Escaping their native Scotland, a country reduced in opportunity due to war and famine, William and John Robertson emigrated to Van Diemen’s Land in 1822. The brothers were granted 700 acres each at Campbell Town and were soon setting up their new properties.

Their younger brother James arrived in 1825 and was granted 800 acres near Richmond. He was followed in 1829 by the two youngest siblings, Daniel and Christina, accompanied by their older brother John who had returned home to bring them out and to buy stock for a new venture that the brothers were planning. Financed by the sale of their two farms, William and John set up Robertson Brothers, an early department store on the corner of Elizabeth and Collins streets in Hobart. The business thrived and it soon expanded to Launceston where James and Daniel operated their own store. By 1835, the four Robertson brothers, and their sister Christina and her husband Archibald Smith, were established members of Tasmanian society.

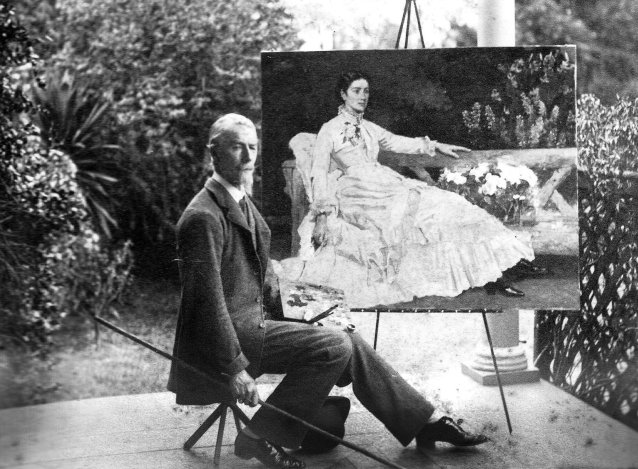

At the entrance to the Art Gallery of South Australia’s colonial collection is a set of family portraits of John and William Robertson, William’s wife Margaret (née Whyte) and their eldest daughter Jessie, painted in Tasmania in the 1830s and 1840s by Thomas Bock. The artist was also among the early adopters in Australia of the new photographic technology developed in France by Louis Daguerre. With careful preparation and skilful handling, this process produced the first true-to-life images of its subject matter.