For ages I tried to find out where this motto originated, in what if any Classical source, or else adapted from what ancient, medieval, or even Renaissance model. None appears ever to have been proposed, so I made discreet inquiries. My learned colleagues Tristan Taylor and John Dillon, formerly of the Yale University Department of Classics, eventually proffered excellent advice, as follows. Quocunque aspicias hic paradoxus erit is certainly not a Classical quotation. Only Ovid is known to have combined the words “quocunque aspicias” or “quocunque aspiceres,” and he used the phrase twice in describing Tomis, his bleak place of exile in Scythia Minor on the Black Sea (modern Romania): “quocunque aspicio nihil est, nisi Pontus et aer / fluctibus hic tumidus, nubibus ille minax,” that is, “In whatever direction I look, there is nothing except sea and air, one swollen with waves, the other menacing with clouds” (Tristia, 1.2.23–24), and “quocumque aspicias, campi cultore carentes / vastaque quae nemo vindicat arva iacent,” that is, “in whatever direction you look, fields lie lacking cultivation and vast fields no one claims” (Epistulae ex Ponto, 1.3.55–56). If the Tasmanian Society of Natural History composed its motto as a conscious allusion to Ovid—and the Vandiemonian setting might indeed suggest logical, if rather gloomy grounds for alluding to Tomis—they did it very well indeed, because Quocunque aspicias hic paradoxus erit parses in elegiac meter; specifically as the second line of a carefully crafted couplet. The long and short syllables of the motto are: _ _ _ . . _ _ . . _ . . _ (provided we elide the -que with asp-, and treat them as one syllable, specifically the third long one.) This is extremely skilled Latin poetic composition.

As for the translation, paradoxus is masculine, so it must refer to the platypus itself because a paradox in Latin is otherwise neuter, i.e. paradoxum. It follows, then, that the word hic is not an adverb meaning “here” but a masculine singular demonstrative pronoun, “this (creature),” referring to the platypus, agreeing thus with paradoxus. Literally, then, the motto translates as “Whichever way you look [at it], this [creature] is baffling,” that is, from the front or from the back. Smoothing out the awkward English, and taking into account the fact that the Classical Latin adjective paradoxus means something closer to baffling, strange, or surprising than literally paradoxical, a neater translation might be: “Whichever way you look at him, this fellow will surprise.” So who on earth in Hobart Town was the composer of this fragment of Latin elegy, and possibly a clever pasticheur of Ovid as well? One should never underestimate the sophistication of nineteenth-century British colonists’ Latin.

Two stray references in the Vandiemonian press from the 1830s cast a ray of light upon the imminence of Ovid in colonial letters—and may suggest contexts in which to place the Latin motto of the Tasmanian Society of Natural History, “Quocunque aspicias hic paradoxus erit,” and its choice of emblem, the curious platypus. The first occurs towards the end of a long article entitled “Van Diemen’s Land, Viewed as a Penal Colony,” that was published in the Hobart Town Courier on Saturday, June 26, 1830. That article sought to correct the false impression circulating at home in England according to which a sentence of Transportation was apparently regarded as more of a blessing than a punishment. As a corrective, the author sketched in considerable detail the conditions of life endured by convicts, concluding thus:

If he forgets himself at the close of day and is absent but for a few minutes, he is put in a dark cell and tried for the omission next morning before the magistrate. But if by some means he is able to indulge in the vicious appetite for drink, under the pretence of driving from his memory the incessant recurrence of former days, of cooling for a season the yearnings after those that are absent, in the fumes of inebriation, he is forthwith visited with punishment commensurate with his crime. But if he fall into the habit of drinking, (for it wants but a beginning) in addition to the slow but sure and fatal effect of the internal poison, he has to endure the repeated infliction of corporeal pain, and the exaction of toil when his wasted and diseased frame is least able to bear its fatigue. Let no one believe that this picture is exaggerated or unreal. Since the most remote times it has been the failing of weak minds in distress to fly to stimulants for relief. Ovid in the beautifully plaintive elegies which he wrote during his banishment, describes himself, even with his enlightened mind, as falling into the same error, and drinking whenever he could obtain the means of indulging in it, at the cost even of his life, to drown the recollection of home:— ‘Hos ego qui patriae faciant oblivia, succos / Parte meae vitae, si modo denture, emam’ [Epistulae ex Ponto, IV.10.19–20]. How wretched then must he be, who purchases a momentary forgetfulness of his condition at so dear a price, and however well deserved no one who reflects upon it will deny, that to him at least transportation to Van Diemen’s Land is indeed a punishment.

Enough people knew their Ovid—backwards—not to need to identify the quotation here. Today, that is mighty humbling. Though the temperance standpoint is striking, this and the rest of the account is not without compassion, and it is striking therefore that the author explicitly refers to the Epistulae ex Ponto, as indeed the compositor of “Quocunque aspicias hic paradoxus erit” seems to allude to the Tristia.

The second reference is more garrulous, but no less intriguing. It is contained in an announcement by James Ross of Paraclete, Knocklofty (1786–1838), of the publication of his Hobart Town Almanack and Van Diemen’s Land Annual for 1835 (Hobart Town Courier, Friday, January 30, 1835):

I consider it my duty to explain the lines I have extracted in my title page, from my esteemed friend Ovid (I like to esteem my friends, and to have friends to esteem), I mean as a poet—‘Judge favourably,’ he says, (that is I say) ‘of my unassuming labours, which I have been induced to undertake, not for the sake of fame or reputation, but in order to be useful, and as a duty I owe to my countrymen.’ The same author has well described the colonist Janus [Fasti, I]—the tutelar saint of January—as having two faces, one looking on the past, and the other on the future, and he might, I think, with equal propriety, have gone on to fill up the lineaments of the one with joy, and of the other with sorrow, for who is not touched by these mingled emotions at the commencement of a new year, contiguous as it is with the blessed nativity, full of joy and poignant commiseration? The lapse of time is ever a serious thought, while we rejoice at the opportunity it affords us to begin a new and reformed era. Good and evil are mixed with every thing mortal—we must pass over the one as lightly as possible, while we dwell upon and make the most of the advantages of the other. And this is exactly the case with the following pages—the candid reader will overlook their imperfections, availing himself of whatever information or amusement they, at the same time contain.

Ross’s reference to Ovid’s Janus/January at the beginning of the Fasti is a conceit tied primarily to the calendar, but it is tempting to point to its push-me-pull-you quality, its front-and-back, past-and-future dualities of conditions in Van Diemen’s Land as neatly congruent with the lingering puzzlement over the physical attributes of what was still known as Ornithorhyncus paradoxus. And, sure enough, there he is, dangling intriguingly at the very end of the table of contents that follows Mr. Ross’s chatty advertorial: an article about the self-same platypus.

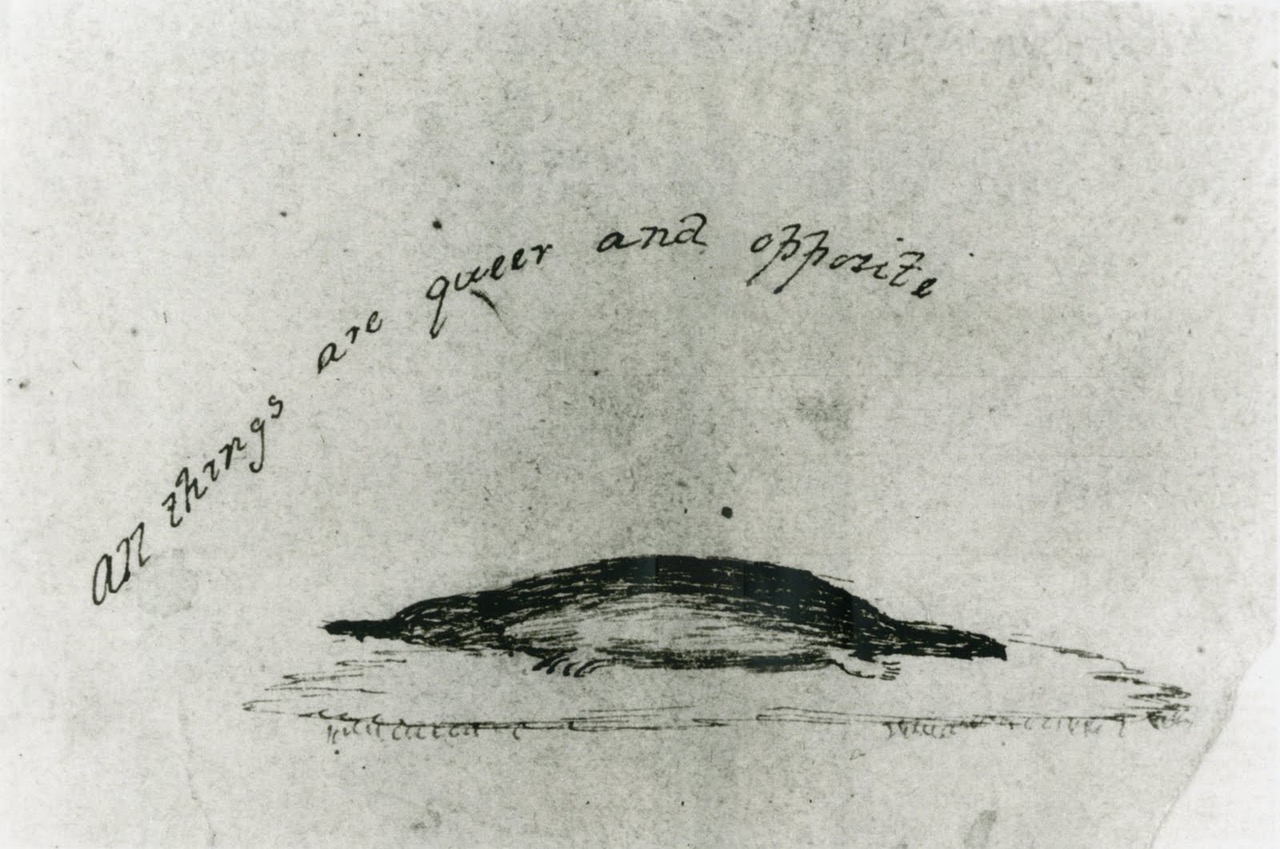

In any event, in my gradually accumulating experience, all things definitely do tend to be queer and opposite, if not at first then eventually!