European painters always enjoyed a good deal of latitude in the representation of angels, those asexual, bodiless, celestial regiments of God, so long as they were young and beautiful. But who can fail to be startled by an oil painting in which, over his canonical pair of feathery wings, a particular, named angel wears the attire of a swashbuckling, early seventeenth-century Flemish militiaman—a broad-brimmed hat, slashed sleeves, lace collar and cuffs, a sword, black stockings, crimson garters and matching bows on his shoes—and cheerfully takes aim with a big, spluttering harquebus, the ignited match cord carefully slung from his left hand? Why is he opening fire on the heavens? And, apart from the specialist, who at first glance would place this delightfully batty Baroque picture in the vicinity of Cuzco in the Viceroyalty of Peru, or indeed date it to the third decade of the eighteenth century?

The Viceroyalty of New Spain

by Angus Trumble, 1 May 2017

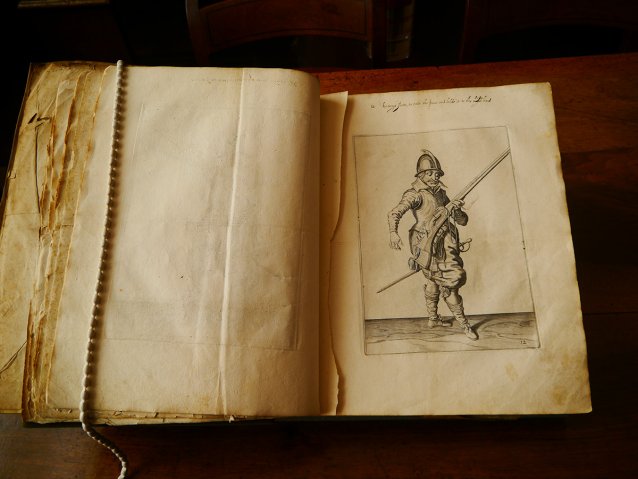

For “Asiel Timor Dei”, ca. 1728 (“Asiel, Fear of God”—the name comes from the apocryphal Book of Enoch), belongs to a cluster of gun-toting “harquebusier” archangels from indigenous villages in what is today the Puno province of southern Peru and the La Paz department of central Bolivia. Derived from printed illustrations in an old Dutch firearms manual by the (ironically) Protestant Jacob de Gheyn, published in The Hague in 1607, the purpose of these pictures was to supplant the local cult of the stars with that of the angels, the heavenly army of the Catholic Church, who could rein in the sun and harness the wind along the shores of Lake Titicaca, and keep the stars in line. They were popular in the first decades of the eighteenth century, and immensely successful in achieving the desired outcome for the colonial and ecclesiastical authorities in Lima.

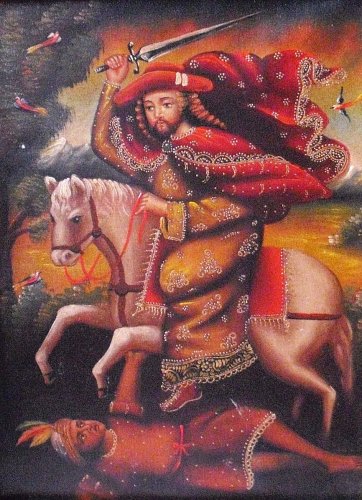

How did the Spanish crown and the Catholic church so spectacularly succeed in evangelizing the Americas, in the forthright manner of “Asiel Timor Dei”? The remarkable part of the story is not so much that this was achieved so early and so completely, built as it was on foundations of terrible brutality, but that, despite this, the many thriving indigenous traditions and cultures found it possible to impress themselves so powerfully on the otherwise inflexible superstructure of Catholic dogma, above all through the visual arts. Again and again indigenous Mesoamerican traditions and the Counter-Reformation church show themselves to have been almost uncannily responsive to each other’s vast repertoires of imagery, producing bizarre, and at times obviously experimental concoctions such as the Mexican “Santiago Mataindios” (St. James, the Killer of Indians); Guatemala’s grotesque crucified infant Jesuses; the Virgins of Quito (Ecuador), Copacabana, Aranzazu (both Mexico), and of the ore-laden “Rich Mountain” of Potosi (Bolivia), to say nothing of the Christ Child of Huanca (Peru); Mexican dead-baby portraits and the Franciscan martyrs of Japan, in which Mexican criollos masquerade as the original Japanese converts.

The hot-blooded spirituality of one family of cultures obviously took up with such zeal the challenge of finding a workable accommodation with the other that, to this day, many pilgrims approach the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe on the outskirts of Mexico City on their knees, some from the very bottom of the subway steps, so profoundly important in the New World consciousness is this relic of the first apparition of the Virgin Mary (disguised as a local, Aztec-speaking princess) to an indigenous American man, Quauhtlatoatzin. Following the apparition, barely ten years after Magellan’s circumnavigation, Quauhtlatoatzin was baptized by the Franciscans with the name “Juan Diego”, at about the time silver ore was first discovered in huge quantities, the first printing press commenced operation in Mexico City, and the Portuguese and Spanish crowns reached a sort of agreement about how to divide the entire continent between them. This was only a few years after Hernan Cortes butchered Moctezuma II, hanged his heir Cuauhtemoc, and rolled out over their splendid Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, a new plan that would eventually turn it into Mexico City.

Barely two years later, Francisco Pizarro conquered the Incas, had Atahualpa first baptized, then garotted, and pocketed the fabulous ransom. Machu Picchu had only been completed thirty years before that. The Incan civilization was a peaceful one, obliterated at its very peak. In Rome, meanwhile, Pope Paul III found that American Indians were “truly men”, and that Christian princes were therefore obliged to instruct them in the faith. In the circumstances it seems incredible that the droves of Dominicans, Augustinians, and in due course Jesuits who followed in the discalced footsteps of the Franciscans should have managed to achieve even a toehold, much less the conversion within decades of huge portions of an entire continent. It is not for the faint-hearted, all of this. Nevertheless it takes you into the cruel and paradoxical heart of colonial New Spain. One sees it in the cold face of Don Jose Antonio Manso de Velasco, Count of Superunda, Viceroy of Peru, in his portrait by Jose Joaquin Bermejo of Lima, and even more frighteningly in that of Elvira de San Jose, Mother Superior of the Convent of Santa Ines in Mexico, a hard scowler, here portrayed post-mortem, wearing a rather fetching crown—church and state, iron hand in silver gauntlet.

Perhaps even more surprising is the degree to which Spanish and Portuguese trade throughout South, Southeast and East Asia shaped the decorative arts in New Spain. Everybody knows that transatlantic shipping brought slaves from Africa to the Americas, but the voyages of tiny galleons back and forth across the Pacific from the second quarter of the sixteenth century onwards brought from Manila, Macao and Malacca to Mexican and other ports in the Viceroyalty a flood of Chinese and Japanese imports to which, in different measure, local artisans responded with brio, always maintaining a vigorous determination to borrow and adapt, not merely to copy. As a result the arts of the Viceroyalty fizzed with unquenchable curiosity and inventiveness.

Chinese lacquer, for example, nudged Colombian craftsmen towards entirely new uses for their own exquisite pale green mopa mopa resin, an almost identical substance used in New Spain for similar purposes. Suddenly the art form became far more ambitious. Indigenous carpenters learned complex joinery from example, and the ceaseless demand for church furnishings, bishops’ thrones and confessionals kept them busy for the next 300 years. Meanwhile, the blue-and-white ceramics of Puebla de Los Angeles in Mexico were directly inspired both by Chinese export ware arriving from the Philippines and by maiolica from Europe. At times you see the decorative conventions of both fused in one Mexican vessel. Displaced Islamic motifs also come from both directions, conveyed eastwards from Asia through the textile trade, and from the Chinese end of the Silk Road, and quite separately, westwards, through the lingering influence of Islam in the arts of southern Spain. (Ferdinand and Isabella finally ejected the Nasrids from Granada in 1492, the same year in which Colombus set sail, and barely forty years before the apparition of Our Lady of Guadalupe, so the Islamic heritage of the Viceroyalty was at first a matter of living memory.)

Glorious Chinese shapes, profiles and types of vessel converse with the rich indigenous ceramic traditions of the Andes, while from 1614 Japanese folding screens or biombos (the criollo name is actually derived from the Japanese term byobu) provided novel formats for conventional oil paintings in the European idiom, principally views of Mexico City. Similarly, indigenous craftsmen took up Chinese ways with tortoiseshell and mother-of-pearl inlay, and employed them with unrestrained vigour. These rapidly evolving New World hybrid species of object reveal not only the impact of the global trade routes, but also found their way back into the markets of Europe and Asia, so that questions arise as to the nature of the reception of Chinese export wares in Spain and Portugal when obviously related New World products often displayed comparable motifs and designs, at times revealing the wildly complicated and intriguing stylistic recension of particular motifs. Where did the connoisseurs stand on the relative merits of each? Did they ever get unusually crude Chinese export and exceptionally refined Puebla wares hopelessly mixed up?

Silver objects, meanwhile—huge gilded altar candlesticks from La Paz; liturgical vessels such as shapely Brazilian flasks for various types of holy oil; weird local monstrances and arm reliquaries; the waist-high solid silver brazier and shovel that were used to heat a church with burning coals on the Altiplano, Bolivia; and above all, the extravagantly eccentric mid-eighteenth-century silver water heater affectionately crafted in the shape of a turkey with splendid plumage (possibly from Lima, ca. 1750)—all these serve to demonstrate the limitless wealth of New Spain, the archetypal El Dorado.

Furniture also demonstrates the busy fusion of European, Asian and indigenous American traditions of design and manufacture. An early eighteenth-century Mexican armchair, for example, the upper portion of which follows a sixteenth- or seventeenth-century Spanish prototype, perches eccentrically on Chinese cabriole legs into which are carved Tlaxcala masks and other indigenous polychrome ornament, all joined, finally, by carved and gilded rocaille cross-members in the latest French fashion. The surprising thing is that this crazy piece of furniture somehow manages to hang together, and that the maker and original customers for similar, whimsically identikit chairs evidently thought so too. In fact, the eighteenth-century New World taste for archaicizing sixteenth-and seventeenth-century Spanish furniture, long after the Bourbons took over the Spanish throne, may have been a deliberate effort to allude to the aristocratic grandeur that was more readily associated with the supplanted Habsburgs, particularly among fantastically rich criollo patrons such as Don Antonio Pacheco y Tovar, Conde de San Javier, and his bride, Dona Teresa Mijares de Solorzano y Tovar, of Caracas in Venezuela. (Seventeenth-and eighteenth-century Spanish vice-regal titles make even the grandest in Debrett seem positively meagre.)

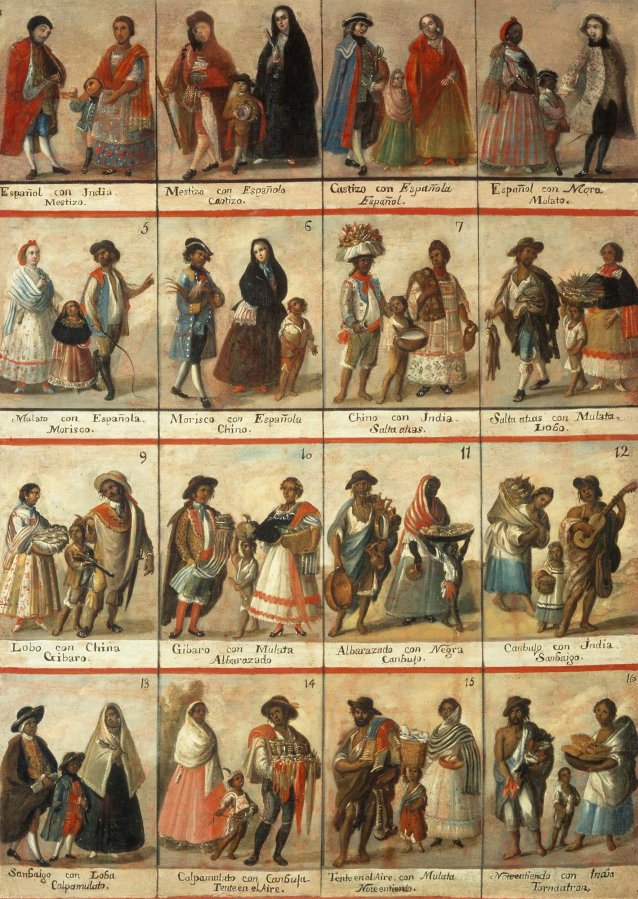

A further revelation is the attitude on the part of this increasingly polyglot string of colonial societies towards murky questions of ethnicity. This emerges from casta paintings, that is, sets of fourteen to sixteen canvases with three quarter-length, three-figure subjects that portray racial mixtures (always father, mother and son or daughter), a unique genre invented in the early eighteenth century for export to Spain. The permutations include the carefully differentiated progeny of Spanish and black (mulatto); Spanish and mulatto (morisca); Spanish and Indian (mestizo); black and Indian (china cambujo); china cambujo and Indian (wolf); wolf and Indian (albarazado); albarazado and mestizo (barcino), and so on down the line to unconverted or “gentile” Indians who were known to exist outside the range and beyond the reach of viceregal civilization, mainly in the Amazon Basin.

These invariably mixed families are represented in harmonious domestic settings that dwell especially on American produce such as chocolate and tobacco, and even, in the case of the gentile Indians, clothing made from brightly coloured feathers, a harvest of tropical gourds and freshly slaughtered armadillo. In most cases, while costume is used to differentiate between regions, it is also used to suggest that in New Spain distinctions of rank take precedence and, at times, supersede differences of race and ethnicity. To what extent the casta paintings reflected a determination on the part of the Viceroyalty to counteract any misgivings at home arising from two centuries of Spanish and Portuguese miscegenation in the Americas, or indeed that these friendly scenarios disguised less attractive realities among the increasingly diluted Spanish criollos of the New World, is not easy to discern, though the genre does push firmly towards a different kind of social, racial, indeed increasingly national set of identities that by the end of the eighteenth century lay at the heart of robust movements towards independence from Spain and Portugal.

So much of this must strike us as impossibly distant from the colonial experience of nineteenth-century Australia. However it is hardly an unreasonable leap to imagine a small flotilla of Spanish vessels dropping anchor at Port Jackson in 1688, and not the British 100 years later. Had this happened, I suspect the arts of the Viceroyalty of New Spain would be far more familiar to us, and these lines would probably have been written in Spanish.

Related information

The Gallery

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!

Support your Portrait Gallery

We depend on your support to keep creating our programs, exhibitions, publications and building the amazing portrait collection!

Plan your visit

Information on location, accessibility and amenities.