I keep going back to Cartier: The Exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia next door, and, within the exhibition, to Princess Marie Louise’s diamond, pearl and sapphire Indian tiara (1923), surely one of the most superb head ornaments ever conceived. Remodelled for the Coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in 1937, Louie bequeathed the tiara to the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester from whom it passed to the present Duke and Duchess, who with extraordinary generosity agreed to lend it. For sheer gob-smacking splendour, though, it’s hard to surpass the Maharajah of Patiala’s immense, almost waist-length 1928 five-strand coronation necklace with its vast stones.

Poise and Carats

by Angus Trumble, 30 April 2018

The other thing I keep going back to is the huge, 1921 478-carat sapphire pendant that once dangled at the end of Queen Marie of Rumania’s sautoir, a wholly dazzling stone the depth of whose colour recalls deep Melanesian reef water just before sunset. It lifts the spirits, this show, largely because there is also a comic element, at least there is for me. Many of the precious objects in it would be shockingly, stupendously vulgar had the Maison Cartier not so spectacularly smashed through the in many ways feeble, certainly half-hearted, barrier marked vulgarity—as in Wallis Windsor’s perfectly hideous 1947 amethyst, turquoise, diamond, gold and platinum “bib” necklace, for example. One is simply carried into a different place altogether.

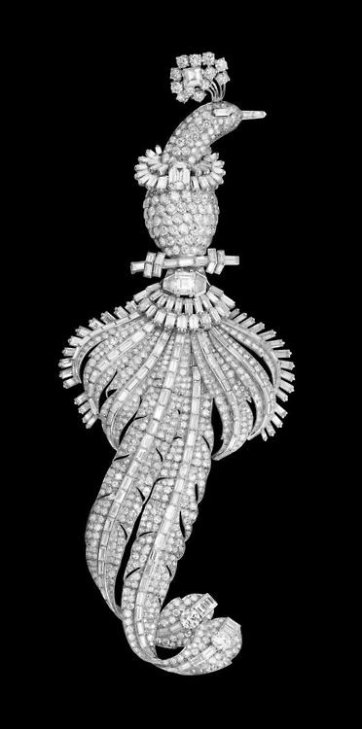

The cover illustration is particularly well chosen. It’s a detail of the object known simply as “bird brooch” (1948): platinum, white gold, 1 emerald cut diamond; two square shaped diamonds; 991 baguette-, brilliant- and fancy-cut diamonds, 20.5 cm high. Nothing better illustrates the wry wit of Cartier’s house style, absolutely undimmed by the grinding years of the Second World War, or perhaps inspired to even greater effusion by the exhaustion and relief of allied victory. It’s a bird of paradise, whose eye, beak, collar, claws, cheekily (and naturalistically slanting) perch, but above all the gloriously long tail feathers are all “drawn” with hundreds of baguette-cut diamonds (all of approximately the same size), so exquisitely arranged and mounted that they capture in the whole exactly the febrile motions and the shiver and shimmy of the bird itself—topping it off with a cheeky flounce of the crest (a big square-cut diamond with a bunch of brilliants held aloft by five slender wobbly platinum shafts), the equivalent of a little exclamation mark. The choice of baguettes, so determinedly, almost industrially rectangular, is no accident.

This incredible object, this rare bird, is neither literal but nor is it a caricature either. It’s an unequivocally Modernist thing of rare beauty, a hymn to the art of the jeweller—more like an oratorio. However, it also put me in mind of a review of a book about fashion shows and Modernism that I wrote some years ago (the review, that is, not the book) in which a number of points apply rather neatly to the workrooms and house style of Cartier on both sides of the English Channel through the same period. I take the liberty of reproducing it here, and offer it most sincerely as a bouquet to my esteemed colleague Gerard Vaughan upon his approaching retirement:

Caroline Evans

THE MECHANICAL SMILE

Modernism and the First Fashion Shows in France and America, 1900–1929

331pp. Yale University Press. £30.00.

978 0 300 18953 7

Mannequins tall and graceful sweep every afternoon through the vista of salons, dragging their spangled, velvet, and shot silk iridescent trains over the thick grey carpets. They reflect in the high wide mirrors; they stand before patrons, seated, breathless with the loveliness, in the deep divans and the beautiful grey chairs with their blue upholstery. (Chicago Daily Tribune, September 1919.)

The mannequin moves slowly from one end of the room to the other, passing before the long mirrors with her head poised like that of some long-plumed bird. There is a murmur of delight—little exclamations of wonder; jewelled women straighten their slender backs with interest. The mannequin walks slowly to each group; her head is a marvel of indolence and grace. She pauses a moment between parted curtains. The gown is a success. (Harper’s Bazar, November 1921.)

Nearly 1.4 million French soldiers were killed during World War I, and approximately 4 million more were wounded. Estimates of French civilian casualties vary, but approximately 150,000 seems likely, while a further 200,000 mostly young French men and women perished in the 1918–20 Spanish Influenza pandemic. Against this background of almost inconceivable grimness, such languorous scenes of immediately post-War Parisian haute couture, described here to readers in the United States—the jewels, trains, mirrors and divans—seem deliberately perverse, as much an exercise in forgetting as in what we would call “high-end shopping”, and certainly a plucky continuation of showroom rituals that were well established in the Edwardian period. It is almost as if the Great War had not happened.

This hugely ambitious, densely argued and extravagantly illustrated book makes the case that between 1900 and 1929 the fashion show was an important point of convergence for a number of separate histories “that are rarely written about together: those of business, international trade, consumption, women, work and fashion, as well as of cinema, revue theatre, and visual art.” These shed much light upon the development of an increasingly global, commercialized and rapidly democratizing modernism in art and design whose principal energies passed back and forth between France and America, continually stoking each other. Evans’s subject therefore extends far beyond the comparatively recent efflorescence of studies in material culture and fashion history, so the old distinction between “high” and “low” in modernist culture largely dissolves when subjected to her careful analysis. No doubt Clement Greenberg and many other critics of the High Modernist school would have resisted the idea that No. 5 by Chanel could be a work of art in many ways as “modernist” as Piet Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie, or an evening dress with opera coat by Madeleine Vionnet et Cie., or George Melford’s hugely successful silent film The Sheik, starring Rudolf Valentino—all were created in 1921.

Yet Evans’s tightly woven history, in which “soft” media, even ephemera, are taken every bit as seriously as, for example, Erik Satie’s score for Sports et divertissements (1914), a piano work specifically intended as an accompaniment for fashion modelling, has much to tell us about gender, class, and the hardnosed commerce already underlying the heady effusions of haute couture, as well as “the rationalization of the body” through the decades at either side of the Great War. In several important respects such “synchronic and diachronic” histories form a continuum, just as the rational, streamlined feminine form of the 1920s in fact originated before the War, borrowing heavily from the language of modernism in art, while, in turn, serving to entrench and nourish it in painting, sculpture and architecture. Thus Francis Picabia’s surrealistic Portrait d’une jeune fille americaine dans l’état de nudité (1915)—nude girl as shiny mechanical spark plug—relates as much to new ideas swirling through the workrooms of the House of Worth or the Maison Paquin as it clearly belongs to a more conventional view of the high modernist avant-garde.

From 1900, Evans argues, responding to many technological developments which had velocity in common, “the desire to see women’s fashion in motion flourished on both sides of the Atlantic, as mannequins tangoed, slithered, swaggered and undulated across the modeling stages of London, Berlin, Vienna, Paris, and New York,” in many cases appearing and performing at racecourses, aboard great ocean liners, and in other public places, not by any means confined to the hushed couturier’s salon. Her contention is that “the mannequin modelled modernism,” and that she was simultaneously a new kind of working woman and a performer of carefully ritualized walks and poses, and of attitudes both disdainful and alluring. These were discussed, analyzed, continually redefined and prescribed for women in print, often with a knitted-brow seriousness that, from our vantage point, strays dangerously toward self-parody. Commenting on developments in the 1913 season, for example, the French journalist Gabriel Mourey described new trends in walking: “Suddenly, miraculously, the stomach is back in its usual place…where were they hiding it yesterday?...Formerly she walked with tiny steps, a neat trot; now she is more relaxed, and freer; where she hid her stomach, she now exaggerates it…And with the stomach, the nape of the neck is also on show for the first time….”

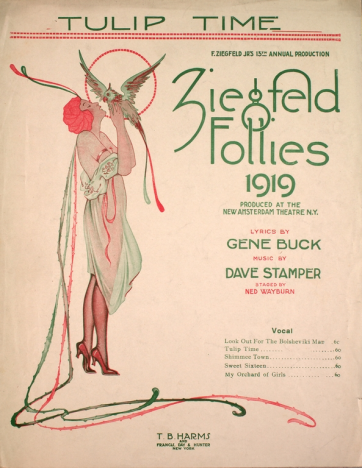

Four years later, Ned Wayburn devised for the Ziegfeld Follies in New York a new fashion-show walk that was described as “a combination of Irene Castle’s flair for accenting the pelvis in her stance, the lifted shoulder, and a slow concentrated gait.” Everything from stance to motion and poise—that now forgotten term, once familiar to millions—was ripe for analysis and scrupulous revision and all of this poured onto the pages of the daily press on both sides of the Atlantic: “Walk like THIS If You Would Be Up-To-Date,” shrieked the Chicago Daily Tribune in November 1912; “Broadway has ‘Fallen for it’—Hard—It’s the ‘Ingenue Crouch,’ a Wiggly, Wobbly, Ambling Stride, Brought Down on Us by the Tight Skirt and the Problem Play.” The mannequin, meanwhile, was a figure of at times of mechanical affectlessness, and, at others, of pouty archness: “a malleable, mobile, gendered, subject-in-process”, who passed effortlessly into cinematic convention, and stands, moreover, in direct relation to the often scarifying “size zero” and heroin chic debates of our own time.

Inasmuch as the author’s conceptual superstructure is obviously huge, her deployment of many different kinds of scarce documentary and visual evidence provides much persuasive ballast, beginning with a chapter on the “pre-history” of nineteenth-century fashion modelling in which, when asked by prospective customers for their name, mannequins generally answered with the mostly alliterative title of the gown or design they were wearing, and never their own. This is the old world of stylistically wooden silhouettes and dummies of Victorian woodblock fashion illustration, as stiff and lifeless as an especially bad Tudor portrait—but soon to be transformed by developments in photography and cinema, and, between 1900 and 1914, “the rationalization of the body” which coincided almost exactly with the rise of the Paris fashion show, “le théatre du grand couturier,” in other words the gilded world of Lelong, Vionnet, Callot, Poiret, Patou and Worth. Innumerable photographs and illustrations reveal here the extent of the shift towards a completely new Edwardian grace in motion and languorous performance, and a freedom of movement visible everywhere from the tennis court to the thé dansant, from the runway to the races at Auteuil—a development that runs closely parallel with what we see in Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912), in turn directly influenced by Etienne-Jules Marey’s time-lapse “chronophotographs” of bodies in motion.

At the same time, Paris couturiers became the subject of widely disseminated newsreel footage shot by Pathé-Frères, a practice that continued through the 1920s. In America, meanwhile, the huge and burgeoning metropolitan department store was a powerful driver both of consumption and performance. Department stores staged fashion shows of newly-minted French gowns, and even positioned living models posing and turning in store windows—a practice objected to at first on the ground of vulgarity. Tableaux vivants, cabarets and other theatrical frameworks served to provide new opportunities for the marketing and display of French fashion in America, while the importance of the American market as a source of income for France rose in direct proportion to the cumulatively disastrous effects of the Great War. In the midst of the horrors of the Marne, for example, Jean Cocteau and Pablo Picasso were photographed at La Rotonde “in the congenial company of Pâquerette, the most precious of Paul Poiret’s mannequins, green shoes, a rosewood-coloured dress, and an indescribable hat,” so recalled André Salmon. (The hat was a sort of cross between a cowl, a wimple, and a pillbox, and does indeed strike one as particularly strange.)

Through the 1920s, the trends were for bigger, faster, more populated shows, larger collections, and a far more widely circulating fashion press. In 1912 if an American dressmaker imported 40 “models,” i.e. finished gowns, each one would be painstakingly unpicked to produce patterns for 25 copies, adaptations, or pastiches. After the war it was many more: “One model, it’s 50–100 dresses,” wrote the Parisian journalist Robert de Beauplan in 1923. “We’re in the kingdom of novelty. Create, create, is the imperious necessity of each day. How many models? This rue de la Paix house produces 700 a season.” All of this flowed into the mirrored halls and fitting-rooms of Wanamaker’s of Philadelphia, Gimbel Brothers, Bloomingdales, and Lord & Taylor. On the French side, Jean Patou engaged an American press agency to syndicate shameless advertorial throughout the continental United States. Patou’s album of press clippings shows that such articles could run simultaneously in up to 49 different American newspapers, with dazzling commercial effectiveness.

In the second half of the book, Evans tightens her focus on the often contradictory worlds of the mannequin—both front of house and behind the scenes, examining in great detail the development of the architecture and decoration of the couture houses, and the organization of their work rooms, dressing rooms, and grand salons, together with the gradual emergence (as we saw in the beginning) of sometimes highly elaborate tricks with mirrors to produce occasionally fragmentary effects of multiplication, kaleidoscopic motion and repetition—recalling Duchamp again, and even the conventions of Analytical Cubism. The paradox is that while the mannequin’s primary purpose was to be as visible as possible, we know almost nothing about their lives.

The Paris salons were carefully regulated so as to detect and eject unauthorized journalists, covert draughtsmen, and even rival dressmakers with a tendency toward copyright infringement. Customers were vetted so as to admit only the wealthiest bona fide American, Mexican and Argentine ladies, whom Madame Grès later remembered as being without exception tall, statuesque, and big-bosomed—a joy to drape. Spies were routinely dispatched to rival houses’ shows, and saleswomen trained to an exacting standard so as to eliminate, even crush non-customers. An American correspondent complained that one Parisian vendeuse had the “indescribable knowing manner of the Parisian businesswoman who, with cold level glances, appraises your exact financial value, and with courteous words and smiling lips that belie the glance compliments you for your residence on the planet while she permits you to see the complete inutility of attempting to get the best of her trained judgment in any particular.”

This perception of the hardnosed business end of the salon was not new. One thinks, for example, of Lady Duff Gordon, the society dressmaker who throughout the Edwardian decade traded as Lucile, Ltd., of 23 Hanover Square and for years resolutely opposed women’s suffrage. Perhaps there is in Lucile’s personal evolution a clue to solving the puzzle of her socio-political outlook, apart from an obvious attachment to what she must have presumed were the views of the majority of her wealthy clients. Lucy Christiana Sutherland apparently detested her first given name, but not enough to dissuade her from trading after her first marriage in the 1890s as Mrs. Lucy Wallace, or later adjusting her name to Madame Lucile, and finally the stand-alone “Lucile”. Yet she was known to intimate friends as Christiana. Upon marrying for the second time she became Lady Duff Gordon, which iteration was evidently interchangeable with Lucile, at least in print. Many of her ensembles carried evocative titles—eventually giving way to a more “modernist” system of plain numbers, made fashionable by Jean Patou in Paris. One of Lucile’s designs specifically referred to the suffragette movement. “A Protest” was an evening gown “in striped taffeta (purple-blue, green and pink) with a chiné [blurry] floral pattern,” a fitted bodice with “a low, off-the-shoulder neckline bordered with purple and green rouleaux [bias-cut piping] within rows of lace and ruched bands of bright green silk. A scallop-edged [white] lace chemisette [worn beneath the bodice] is embroidered with silver bows and slotted with pale blue ribbon, and has puffed elbow-length sleeves gathered by bright green ribbon tied in bows...”

Although she “met and rather approved of Emmeline Pankhurst, describing her in her autobiography as ‘a dear little woman’,” Lucile nevertheless expressed her forthright view that the traumatic pre-war push for women’s suffrage was “a huge joke…a lot of nonsense and rather undignified.” In this instance she went as far as to harness and exploit the signature colors formally adopted in 1908 by the Women’s Social and Political Union: purple for dignity, green for hope and white for purity. No doubt Lucile’s aim, here, was to hedge her bets, in other words to offer “A Protest” to ladies who could either wear those colors with pride, or else with contempt. Yet Lucile was obviously also a shrewd businesswoman of the modern era, recognizing the value of the American market by opening a branch in New York in 1910; diversifying into underwear (for Gimbels’); experimenting with cheap fabrics sourced in the United States; developing new venues and marketing techniques such as “tango teas,” all the while manipulating the press with impressive ingenuity and determination. Eventually she lent her mannequins to the Ziegfeld Follies in New York.

Perhaps the author’s most persuasive general observation about the links between High Modernism and the world of commercial fashion in the first quarter of the twentieth century is suggested by her title. In Giovanni Boldini’s flamboyant portrait of Mrs. Lionel Phillips in Dublin (1903) and John Singer Sargent’s portrait of Ena Wertheimer (1904) both sitters are smiling, a wholly Edwardian development much influenced by developments in photography the rise of early cinema. Smiling, by contrast, is as alien to High Modernist painting and sculpture as it was to professional mannequins: “Again and again, journalists from the beginning of the century commented on the repetitive nature of the mannequin’s smile as if to acknowledge the hollowness at its heart. Her mechanical smile has a precedent in Villiers’s L’Ève future of 1886, in which the android Hadaly is fitted with six stock smiles described by her inventor…” The mechanical, the repetitive, the simplified line and reduced form―these are perhaps the most striking qualities that were consistently shared by the modernist avant-garde and the busy world of haute couture. Both meant serious business.

Related information

The Gallery

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!

Support your Portrait Gallery

We depend on your support to keep creating our programs, exhibitions, publications and building the amazing portrait collection!

Plan your visit

Information on location, accessibility and amenities.