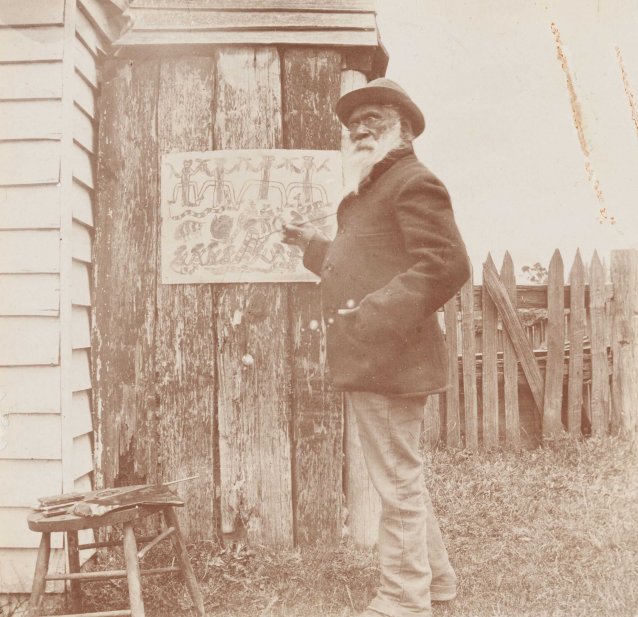

In a way, the National Portrait Gallery, too, started life as part of a library and, like the present-day NGV, shares DNA with a Victorian-era institution – the National Portrait Gallery, London, established in 1856 in the belief that images of eminent personages provided an effective way of educating people about the nation’s history and achievements. One of NPG London’s founding principles was that its collection should prioritise history over art, and that the celebrity of the portrait’s subject outweighed the merits (or otherwise) of the portrait itself. Early moves towards a portrait gallery in Australia were likewise focused on sitters. In the 1890s, Tom Roberts started work on a series of portraits later exhibited under the title ‘Familiar faces and figures’ – a prototype portrait gallery comprised of paintings of 23 musicians, actors and others, each informally posed and minimally rendered on unprimed timber panels as if to suggest something of Australia’s fresh and vigorous national character. In 1910, several years after completing his epic ‘Big Picture’ of the opening of the first Australian parliament, Roberts wrote to encourage the government to keep pursuing the idea of a ‘painted record’ of the nation’s ‘prominent statesmen’. The suggestion led to the establishment of the Historic Memorials Committee, formed to provide ‘consultation and advice in reference to the expenditure of votes for the Historic Memorials of Representative Men’, in late 1911 – and which still oversees the commissioning of official portraits of prime ministers, governors-general and chief justices of the High Court. From the get-go, it would seem, a national portrait gallery was always going to be bedevilled by ideas that categorise portraits as ‘history’ or distinguish ‘portraiture’ from ‘art’. One of them is that portraiture is closely connected to power, pride and publicity, making a national portrait collection routinely subject to perceptions of homogeneity and conservatism, which in turn raises questions about relevance, about who is represented in Australian portraiture and who isn’t and why, and making it difficult to counter the idea that the main role of portraits is to document prominent members of society using a specific set of conventions or easily readable codes.

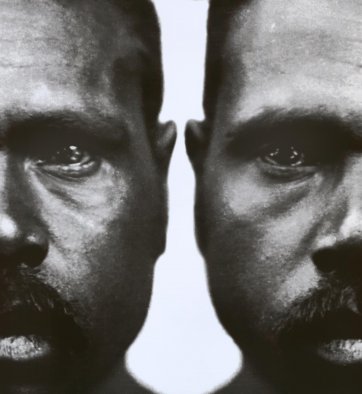

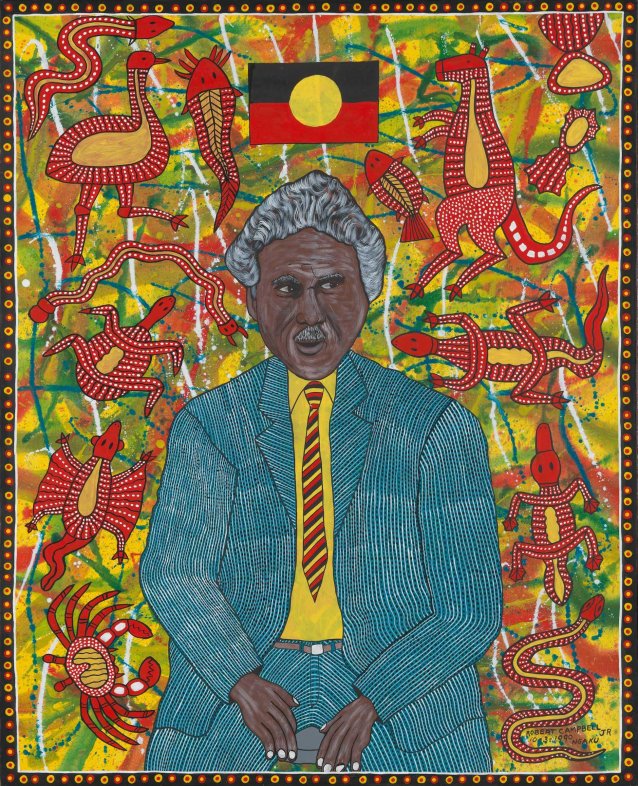

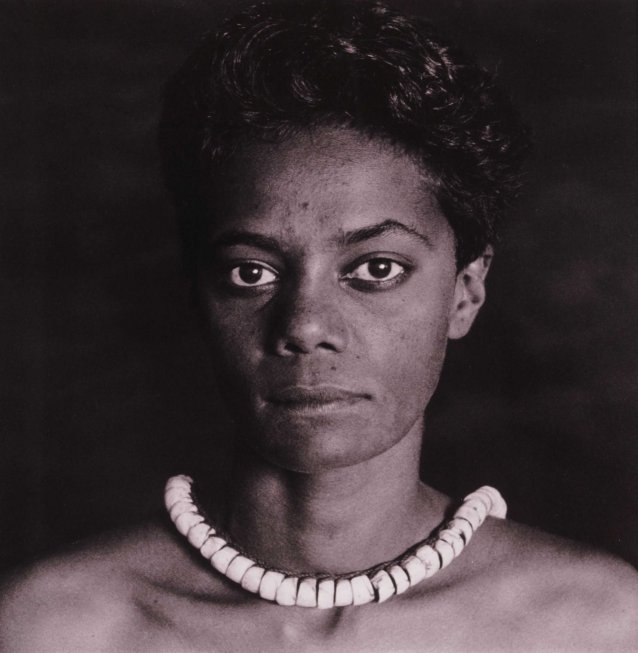

All of this is in stark contrast to the foundation of the National Portrait Gallery in 1998. The NPG owes its existence not to a government or head of state, but to the commitment of its founding patrons, L. Gordon Darling ac cmg and Marilyn Darling ac, who instigated the development of the 1992 touring exhibition Uncommon Australians to ‘bring Australian history to life [and] show some of the strongest and best-known art the country has created’. Featuring 116 portraits in various mediums, the exhibition ultimately resulted, following four years as part of the National Library of Australia, in the establishment of the NPG as an independent institution. Its foundational acquisitions asserted a vision very different to the ‘Memorials of Representative Men’ forecast in 1911, and made a clear statement that the National Portrait Gallery would be a place for testing the possibilities and fluidity of portraiture instead. Jenny Sages’ painting Emily Kame Kngwarreye with Lily (1993), the NPG’s inaugural purchase, shows the esteemed Anmatyerre artist sitting cross-legged on the bare earth and squinting in the sunlight. No formality, no posing, no pretensions. The first photographs acquired for the NPG’s collection were Tracey Moffatt’s The movie star (1985), a portrait of Yolngu man, actor and traditional dancer, David Gulpilil am; and Some lads I (Russell Page), taken in 1986 when Page, a man of the Nunukl (Noonuccal) and Yugambeh peoples, was emerging as a leading contemporary dancer and choreographer. Both works had featured in the exhibition NADOC ’86, which Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi artist Michael Riley considered momentous for being the first occasion where Aboriginal artists ‘were dictating what they wanted to show, and how they wanted to show images of their own people’. And one of the first works commissioned by the NPG – Howard Arkley’s forebodingly fluoro Nick Cave (1999) – is not the result of a sitting wherein the artist scrutinised his subject, but a distillation of the Cave photos, posters and clippings that Arkley collected – just as he used real-estate ephemera as inspiration for his day-glo images of suburban houses and interiors. Each of these exemplifies the unexpected, eccentric or incisive capacity of portraits, and demonstrates how it is that the most effective portraits are often those that challenge traditional perceptions about the genre.

With this in mind, NPG curators embraced the prospect of working with NGV colleagues on WHO ARE YOU, an exhibition that combines works across media, styles and time, and in so doing amplifies the synergies between both collections. Just as the NGV’s official separation from what is now the State Library of Victoria in the 1940s was accompanied by the deaccessioning of its inaugural portrait acquisitions (the Oval Portraits and Summers’ bust of Barry included), the NPG from its outset was upfront about its intention to be a museum of art as much as of people and history. Critically, it made the commissioning of works by leading Australian artists – whether they were ‘portraitists’ or not – a key aspect of

its collection development policy.

As inaugural Director Andrew Sayers explained of the philosophy behind the NPG’s commissioning program: ‘The artist does not necessarily have to know the subject, or have met the subject. Yet there must be some basis – it may be shared background, shared world view or interests, or some stylistic trigger – on which to base the view that the result will be more interesting and more profound than the result of a casual encounter.’