I watched Tea with the Dames again recently. Eileen Atkins rather dramatically recalls pre-stage nerves: on the way to the theatre she often ponders ‘would you like to be run over now?’. Judi Dench and Maggie Smith agree that they find performance scary and indeed that it is ‘scary every day on a film set’ – all the people involved, all the barely suppressed eye rolling and sighing when you flub a line and everyone has to go again. When we see the women for the first time in the garden of Joan Plowright’s delightful country house in Sussex we are given a view of the cine-camera and all those seemingly endless crew people needed to make a film. Then you notice a photographer has origamied himself in amongst it all and is shooting away. Intermittently the Dames somewhat good naturedly but also, to be honest, a bit tetchily complain when the photographer, Mark Johnson, takes shots of them that they think aren’t flattering. Smith asks him if it is his first day at one point and at another, tiring, she dismisses him.

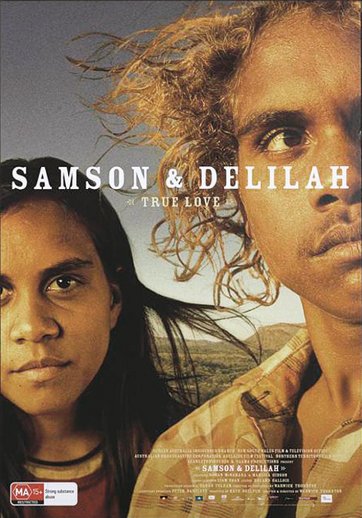

The role of a stills photographer on set is nicely straightforward and transactional, and agreed upon by all, a necessary part of the whole thing. Made for publicity and promotion, a good film still is meant to make us want to get out of the house and into the cinema. The still stirs a desire in the viewer to find out what the plot of the film actually is, to arouse the potential viewer’s curiosity. The image may not appear in the film at all. We are in the territory of what we know photography does so well: arouse our desire to consume things. So manipulative. But also inspiring and seductive. Sexy. Addictive. Current stats around the proliferation of image making and consumption confirm that we can’t get enough of it. (I’m a part of the most photographed generation ever, Marc Fennell laments in a recent interview with Geraldine Doogue on Compass in reference to his struggle with his relationship to his body image.)

But watching the Dames reminds me that we often don’t love being photographed even when it’s part of our job and we’ve signed up for it and the camera loves us. And reading curator Penelope Grist’s catalogue essay in Starstruck: Australian movie portraits (2017) I am struck, as I should be, at the complexity and difficulties the photographer can face in making film stills. Despite a portrait being created from a relationship – of whatever nature, professional, adversarial, intimate, playful – between the photographer and the sitter, the most important thing, the photographers Penny spoke to agreed, is the need for them to be invisible. While still getting the shot/s that will convey the feeling, the overall atmosphere and meaning of the movie. While it is still in the process of coming into being. With limited ability to control the set up or direct the action. That’s the magic of it. Instinct combined with acute observation and a bit of good luck. Good film stills photographers get good at it.

It is a bit of a tightrope walk. The photographer understanding and being able to capture the vision of the director, while staying true to their own. Loyalty to the image but also sensitive to the concerns of the actors. In the Starlight: 100 years of film stills catalogue long-time hugely successful stills photographer Rolf Konow recalls having shots that he thought were marvellous rejected by Julie Christie. ‘Rolf, it’s not your photos I don’t like – it’s me I don’t like,’ she told him. Also, a strange thing: knowing that the images you make may become (fingers crossed) an important part of the cultural landscape while few people outside the industry will know your name – name five important film stills photographers working today.