‘Everything was going to be new; everything was going to be different. Everything was on trial.’

Virginia Woolf

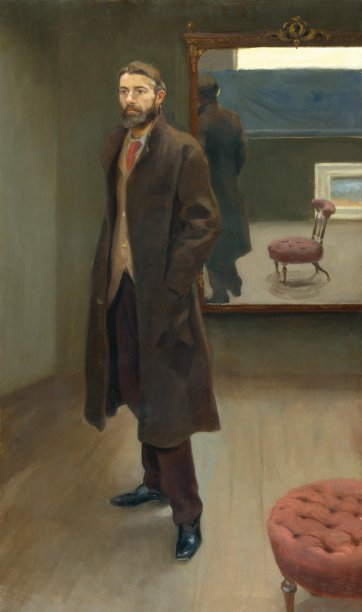

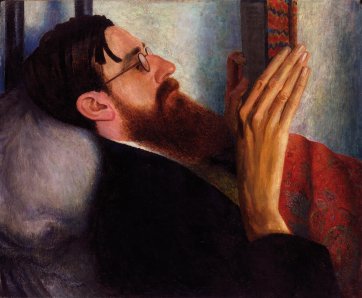

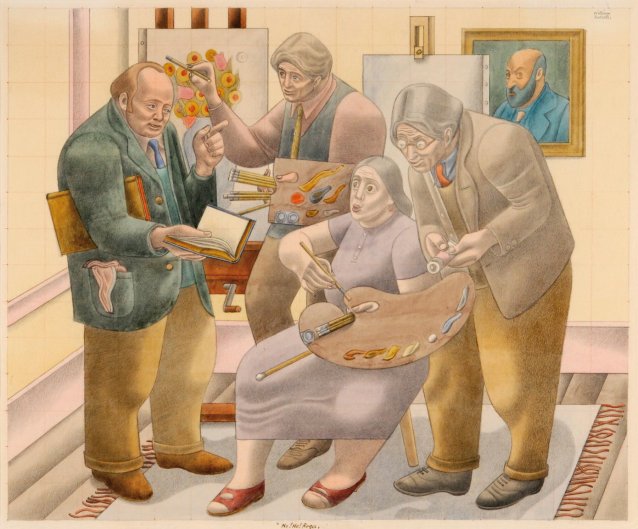

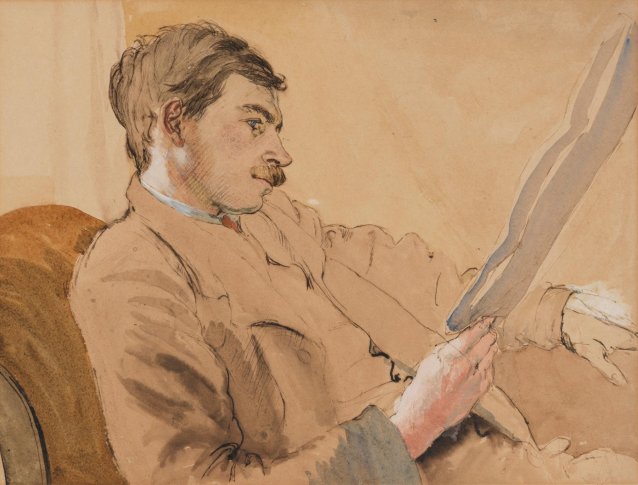

With writers like Virginia Woolf and E.M. Forster, artists Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, and critics Clive Bell and Roger Fry – and a reputation for rebellion, artistic experimentation and sexual freedom – it’s not surprising that the members who made up the Bloomsbury Group are still celebrated today. The recent exhibition Beyond Bloomsbury: Life, Love and Legacy, curated by Becky Gee at York Art Gallery in partnership with the National Portrait Gallery, London, examined the artistic output and personal lives of the Bloomsbury coterie through paintings, sculpture, works on paper and published texts. It also drew on the growing interest in examining the Bloomsbury Group with a focus on sexual diversity and gender identity, and their legacy to the wider queer community and, indeed, to British art.

The show coincided with a new edition of the 1997 book The Bloomsbury Group by art historian Frances Spalding, who has published widely on the principal figures concerned. Yet ‘Bloomsbury’ remains a rather elastic term for a group that was never clearly delineated. It encompassed a fluctuating number of friends whose philosophies, interests, work and relationships overlapped, often harmoniously, and created a lingering mystique or ethos. As the American writer Dorothy Parker tartly remarked, the personalities associated with Bloomsbury, ‘lived in squares, painted in circles and loved in triangles’. The emotional entanglements and unconventional living arrangements of various members of the Group were the subject of bewilderment to many contemporaries and continue to exert a fascination for audiences.

As the art historian Quentin Bell observed: ‘certainly they were not alone in protesting against the irrationality and cruelty of sexual superstition, but I think that they were more persistent and more thoroughgoing than most, if not all, of their contemporaries in their rejection of the claims to establish ethical canons for men and women. To this theoretical extremism they added a kind of cheerful shamelessness which could shock even those who, in principle, agreed with them.’