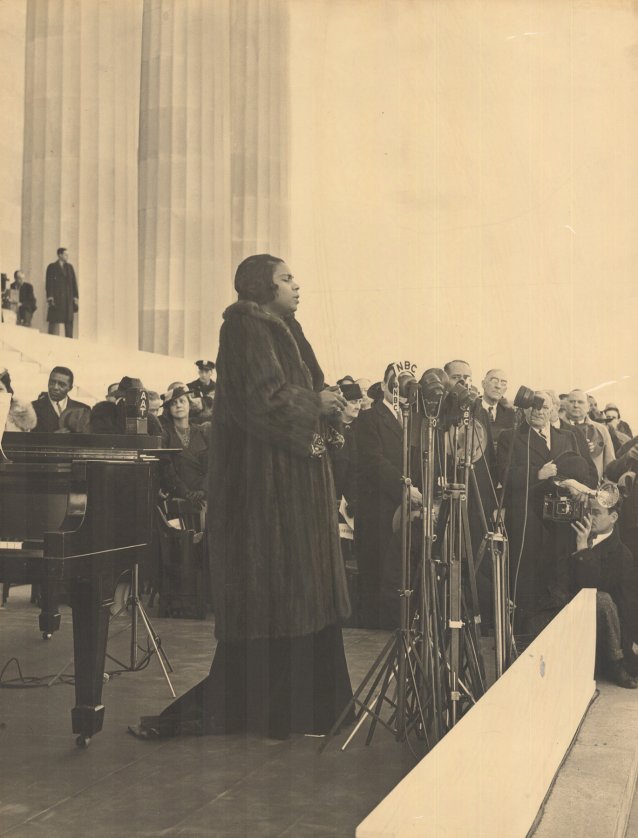

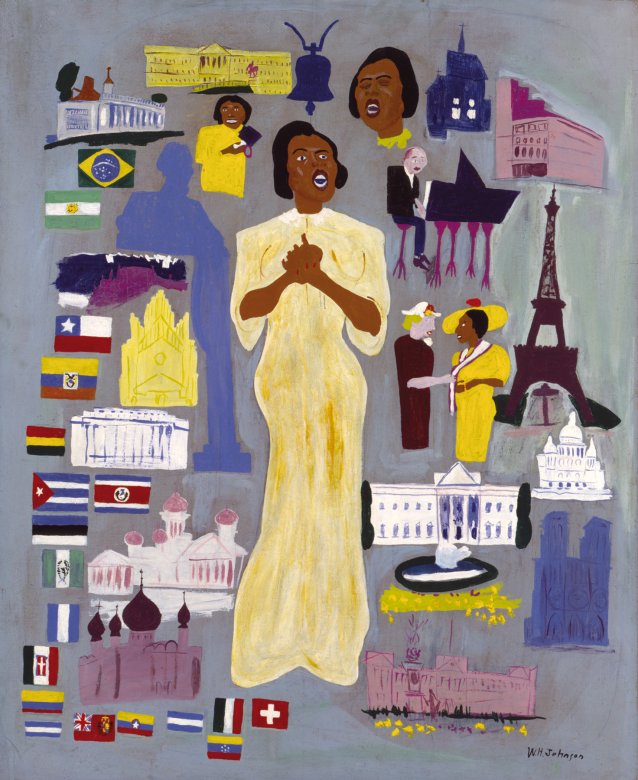

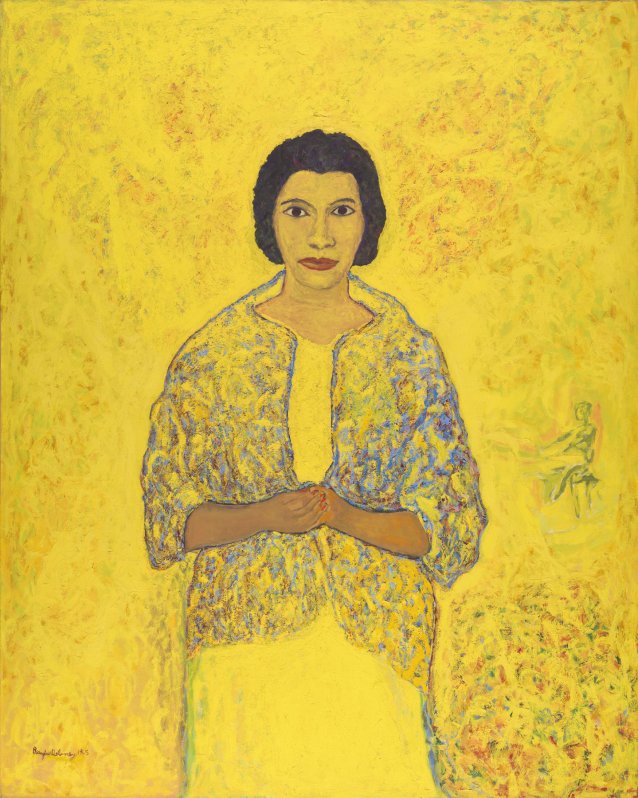

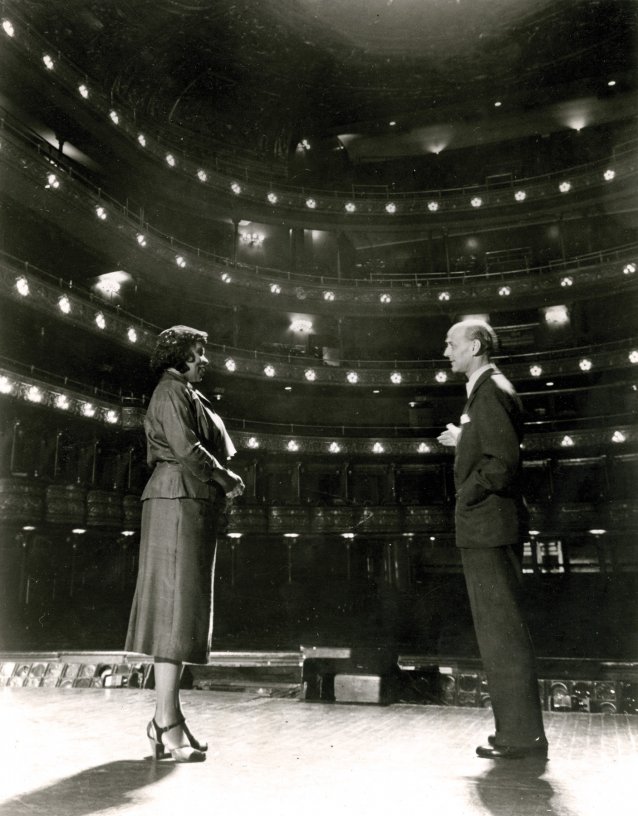

Marian Anderson (1897–1993), the trailblazing contralto, broke boundaries during her long life. To most who have heard her name, she is best remembered for her recital on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on Washington, DC’s National Mall on April 9, 1939. Anderson’s impact on the histories of music and civil rights, however, extends well beyond this one concert. What catapulted her to that temporary stage and what followed are some of the questions that guided the planning of the exhibition One Life: Marian Anderson, on view at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery until 17 May, 2020. As Anderson’s career and the artworks that depict her demonstrate, she continually tested the limits imposed on her by race-based discrimination. Yet she often hesitated in embracing her role as an icon of the American Civil Rights Movement, consistently encouraging a focus on her art instead.

Anderson’s journey to the Lincoln Memorial was a tumultuous one. The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) had rebuffed multiple requests for her to sing at their Constitution Hall. The reaction to the DAR’s spate of rejections – a function of their exclusionary policy prohibiting African Americans from performing at the Hall – was overwhelming. Anderson’s Lincoln Memorial concert would mark the histories of the DAR and the American Civil Rights Movement in stark fashion, determining how the singer, from that moment forward, would be perceived, discussed, and depicted.