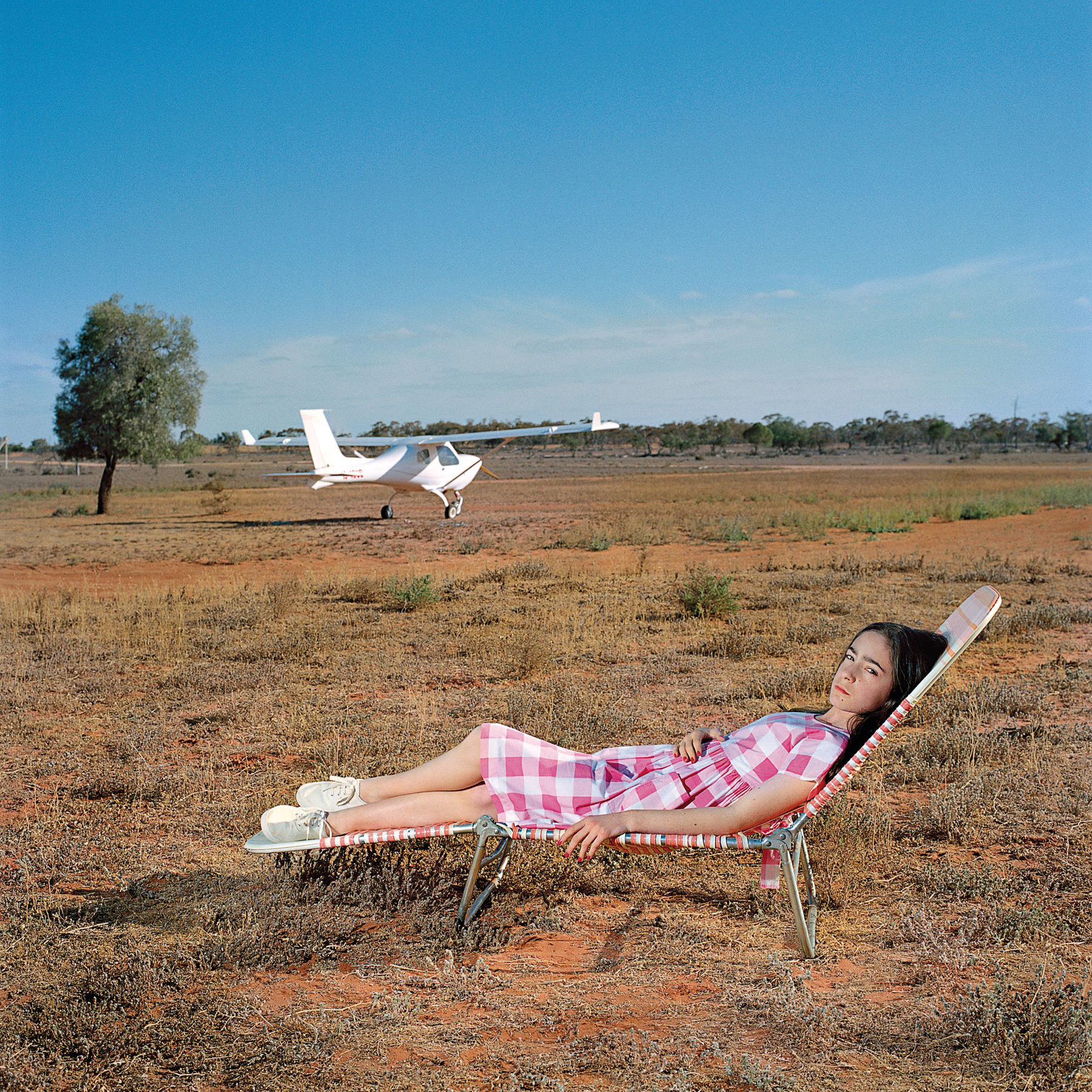

Miles from nowhere, 2008 (printed 2014) from the Games of consequence series 2008 Polixeni Papapetrou

Renowned Australian artist Dr Polixeni Papapetrou (1961-2018) initially pursued a legal career for twenty years, as a business and taxation lawyer, before taking up photography in the mid-1980s.

Papapetrou’s early work was strongly influenced by the photo-documentary style of Diane Arbus (1923-71). In a similar vein to the iconic American, Papapetrou sought out individuals who were marginalised, whether through their status as social ‘outsiders’ or because their interests placed them on the fringes of ‘mainstream’ taste. However fleeting her engagement with the subjects in her various series – among them drag queens, wrestlers and reverent Elvis fans – she had an innate empathy and rapport with those who sought to define their identity through role-play, performance, or disguise.

The birth of Papapetrou’s children would alter the trajectory of her practice, leading to a renewed focus on what she called the ‘liminal and transitional stages in life, such as childhood, adolescence and old age’.

Olympia: Photographs by Polixeni Papapetrou, showing at the National Gallery of Victoria until 15 March, 2020, is the first retrospective of the artist's work, and focuses on images she created of her daughter Olympia Nelson, who was initially a protagonist, and later a collaborator. In the first of these works, the 1999 triptych Infant/Infanta, Papapetrou’s firstborn is a year old, her wide-eyed gaze unflinching before the lens. Wearing a white crochet dress and matching bonnet, and playing with an ornate silver heirloom rattle, she is propped against a tapestry cushion bearing the image of da Vinci's Mona Lisa (La Gioconda) (c.1503-06). The black and white study of Nelson is positioned between two colour reproductions of works by the Spanish pintor de cámara (court painter)

Diego Velázquez (1599-1660).

On the right is one of the painter’s last completed works, Portrait of Infante Philip Próspero (1659), the son of Philip IV (1605-65), who died when he was only three years old. On the left is Infanta Margarita Teresa in a Pink Dress (1653-54), one of five portraits Velázquez produced – between 1653 and 1659 – of the future Holy Roman Empress. This initial portrait of Nelson reflects Papapetrou’s wider interest in the portrayal of children throughout the history of European art, with the traditional poses and pictorial tropes common to the genre. Just as Velázquez documented the Spanish royal family at various points over the 36 years of his employ, this work prefaces the number of times Papapetrou would photograph her children and their friends in subsequent decades.

Growing up in a household that was unusually attuned to art, Nelson was soon fascinated by the room Papapetrou had started to use as a studio for photo shoots. ‘I remember watching Mum take photographs from a young age and I would observe from outside the studio, always full of questions and curiosity. I was so intrigued by the process that I wanted to become part of it’, she admits. ‘I greatly enjoyed the idea that I could put on a mask or a costume and change my entire persona. Always with Mum’s direction, my grandmother (Eftychia) would sew the costumes, Dad would paint the backdrop and Mum culminated everything together by taking the photo.’

1 Olympia as Lewis Carroll’s Xie Kitchin as Chinaman on tea boxes (On duty), 2002 from the Dreamchild series 2003,. 2 Olympia as Lewis Carroll's Beatrice Hatch in ‘Apis Japanensis’, 2003 from the Dreamchild series 2003,. Both Polixeni Papapetrou.

Dreamchild (2003), the second series for which Nelson modelled, was named in reference to the 1985 film that fictionalised the relationship between Alice Liddell (1852-1934) and Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832-98), who wrote under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll. Dodgson took up the fashionable pastime of photography in 1856 and became one of the most accomplished amateur artists of his day. Papapetrou’s doctoral thesis, A Studio Investigation Into the Theatricality and Performative Aspects of the Child Subject in Photography (2006), examined aspects of Victorian-era photography and its themes.

Papapetrou recreated several of Dodgson’s images of his ‘child-friends' such as Liddell, Beatrice Hatch (1866-1947) and Alexandra Kitchin (1864-1925) in a similar highly staged tableaux vivant style. This was the first time Papapetrou experimented with using vivid trompe l’oeil painted backdrops, consistent with the nineteenth-century photographic trope. These large scenes, painstakingly rendered by Papapetrou’s husband – writer and academic Associate Professor Robert Nelson – created a more dramatic setting for their daughter’s portrayal.

1 Prize thimble, 2004 from the Wonderland series 2004,. 2 Flying cards, 2004 from the Wonderland series 2004,. Both Polixeni Papapetrou.

The sixteen works that form Wonderland (2004), arguably Papapetrou’s best-known series, draw directly on the illustrations Sir John Tenniel (1820-1914) produced for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865). An exuberant Nelson cavorts through scenes drawn from this beloved children’s book such as Flying cards and Prize thimble. ‘In order to prepare … we would read together and watch documentaries based on the theme. I was constantly learning and becoming immersed in these stories; and so yes, there was much awareness of a psychological subtext, like the spirit of Alice against arbitrary institutions; but for us the psychology was all in the tale’, Nelson explains. ‘We didn’t ever talk about how people would see the art differently. I like to think that Mum shared my innocence – that for the purposes of making photos there was nothing else in our world but this conversation.’

The eldest child of Greek immigrant parents, Papapetrou found it difficult to reconcile the strong influence of her parents’ cultural heritage with her identity as an Australian, growing up in Port Melbourne. Despite being born here, Papapetrou could not speak English when she started primary school, and her name was anglicised to ‘Pauline’ in a misguided attempt to help her fit in. As both her parents worked, from a young age Papapetrou was responsible for supervising her younger siblings and contributing to household tasks. ‘Curiosity and imagination were not things that she grew up with, and so when she began exploring her own creativity as an artist, she realised that art and performance give children the unique opportunity to dream up an enhanced reality that is immersive’, Nelson reflects. Of the range of characters and guises she had the opportunity to explore through Papapetrou’s work, Nelson says, ‘Mum loved these aspects of the art-making process. She afforded us a childhood that she never got to have, and we gave her back a childhood that she didn’t have.’

1 Delphi, 2016 from the Eden series 2016,. 2 Amaranthine, 2016 from the Eden series 2016,. Both Polixeni Papapetrou.

Delphi, a work from Papapetrou’s Eden series, won the 2017 William and Winifred Bowness Photography Prize. Eden’s nubile young girls are almost subsumed by flowers; the series’ floral crowns and corsages, floral dresses, and vintage floral backcloth prints evoke some idyllic bower, its dwellers still partially shielded from adulthood. Nelson posed for four of the works, including Amaranthine (2016), where she peers from the centre of a pink and red wreath. Papapetrou references the Greek myth of Chloris, the nymph associated with spring, flowers and new growth, and later western traditions of the May Queen, celebrating youth, fecundity and renewal. The pulchritude on display is nonetheless tempered by the knowledge that even the most resplendent petals will fade and wither. Faced with the ebbing of her own life due to metastatic breast cancer, and the sorrow of not seeing her daughter mature, Papapetrou seeks to preserve Nelson’s bloom.

1 Muse, 2018 from the My Heart, Still Full of Her series 2018,. 2 Giving Birth to Myself, 2018 from the My Heart, Still Full of Her series 2018,. 3 I once was, 2018 from the My Heart, Still Full of Her series 2018,. All Polixeni Papapetrou.

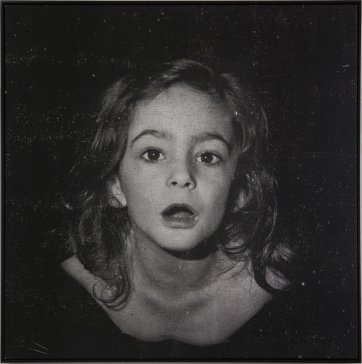

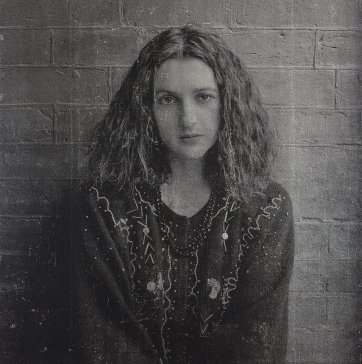

The apotheosis of Papapetrou’s career, My Heart – still full of her (2018), is the first series in which she appears alongside her daughter. The title is taken from the poem Souvenir (1841) by Alfred de Musset (1810-57), a lament about lost love, lingering regret, and mortality. The vibrant colour that characterised many of Papapetrou's previous works has retreated to solemn monochrome, and the medium to silkscreen. Using self-portraits of herself from the mid-1980s and previously unpublished images of Nelson from their many sessions, the artist achieves an eerie, almost spectral quality. The works in the suite are grainy, printed using metallic foil to deliberately reference the more archaic silver gelatin process. ‘Mum created these works on her deathbed. It was a memorable process where she pored over images of herself as well as me. She loved making this work where the two of us are in a sense collapsed as one’, Nelson reveals.

This ambiguity is apparent in Giving birth to myself (2018) where an open-mouthed Nelson gasps as though emerging from the amniotic sac, but paradoxically is far more self-aware and worldly. Muse (2018) honours the symbiotic relation of art to life that Papapetrou and Nelson had embraced throughout their lives, as the artist bids her daughter farewell through the medium they had long collaborated on. The series title expresses the complexity of this bond. Nelson notes, ‘It could be: “As she dies, Mum’s heart is still full of Olympia” or it could be “Now that Mum is dead, Olympia’s heart is still full of her”. In a way we are repositories of all our experiences and that totally indicates a parent’s role. At the same time, I think that Mum would have hoped that I’d be something a bit more than a repository, but demonstrate the same kind of self-determination that she managed, despite the odds.’

I once was (2018) prefigures Papapetrou’s death in April that year, and echoes a comment she made in her last published essay: ‘Only photography and its sister-arts have the power to say “I once was and I was there”. I poetically existed.’ The works that Papapetrou created with her children were, as she observed, like another member of the family. Nelson characterises it in powerful terms: ‘Working on this exhibition has been greatly cathartic for me. Being able to represent Mum’s work is the most special way I could imagine of sharing our legacy as mother/daughter and artist/muse. The way the exhibition takes works from different series manages to narrate our relationship. Here I’m this angel on a cushion; here I’m a mimic of old people; here I’m chirpy companion Alice; now I’m a child who is lost; there I’m already a brooding teenager; and now I transform into extraordinary supernatural apparitions and so on, right down to the end, where I am compared to my Mum in person. I have distinct memories from each body of work and they indeed all unite overwhelmingly in this retrospective.’

As de Musset’s poem concludes:

I loved, and I was loved, and she was fair

This treasure which no death can filch away.