‘I move gingerly around the paintings I own because I know they are looking at me as closely as I am looking at them’, writes Jeanette Winterson towards the end of her 1995 essay ‘Art Objects’. In the piece, Winterson narrates her journey towards becoming comfortable with art: ‘Art takes time. To spend an hour looking at a painting is difficult’, she writes. ‘The public gallery experience is one that encourages art at a trot … Supposing we made a pact with a painting and agreed to sit down and look at it, on our own, with no distractions.’

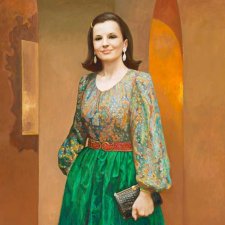

To ‘trot’ less and stop, breathe, engage more. It’s an appealing premise, whether in a gallery setting or applied to anxious, time-poor lives more broadly. For our part, Eye to Eye is a summer Portrait Gallery Collection remix that invites our visitors to make this pact with the portraits. The practice that Winterson describes is what our educators call ‘slow looking’.

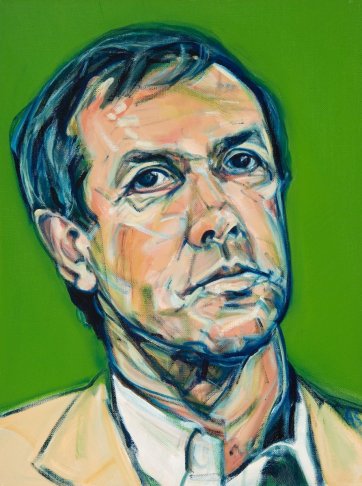

To set the scene for looking slowly, we’ve arranged the portraits by degree of eye contact – in a progression, from eyes clamped shut through to nowhere-to-hide stare. Daily speech and literature are replete with ocular colloquialism, metaphor and cliché: one can sport a glad eye or stink eye; get an eyeful; bemoan an eyesore; eye off some eye candy; or have an eye-opening experience. In portraiture, the eyes are somewhere to begin – they’re a way in, an initial prompt to whet the senses.

The portraits in Eye to Eye are unencumbered by extended text. For Winterson, labels shield us from the full impact of the art. At the risk of surprising, even perplexing, our biography-hungry visitors, this exhibition is an experiment in the practice of looking – then seeing – without distraction, such that what is seen (and felt) comes with time, and is entirely subjective.

As someone who admits to mostly experiencing art at a trot, I thought I should try it for myself during the installation of Eye to Eye. Would it feel superficial? Like I am making assumptions but not learning the real story? Would I be as bad at slow looking as I am at yoga? I was apprehensive.

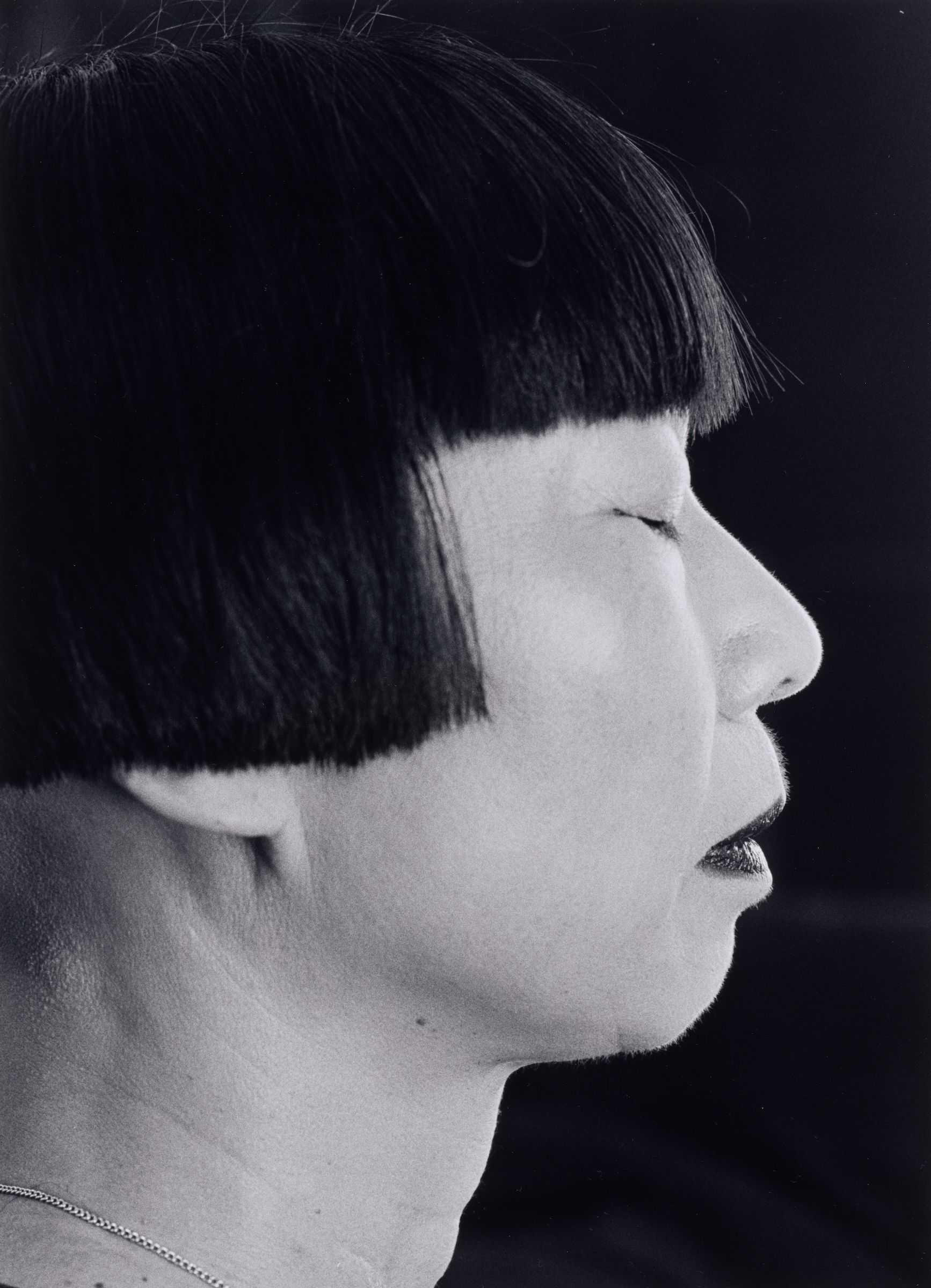

Perched before Greg Weight’s photographic portrait of Lindy Lee, I notice her necklace for the first time. Her sculptural form is human in its imperfection – each strand of hair falls so slightly out of place, and the creases in her skin are at odds with Lee’s stark, deliberate profile. Then I sense the courage and confidence in her closed eyes; where initially I saw vulnerability, I begin to feel strength and calm.