Sometimes you meet people in unlikely places. You make friends under unexpected circumstances.

In 1996 I was Senior Curator of Art at the Tasmanian Museum & Art Gallery, and had the great pleasure of working in the 1807 Government Issuing Store, the oldest element of the museum complex, and, I was led to believe, the oldest continuously-occupied building in Australia. I loved it. The art department office doubled as the print room, and beyond our desks the walls were lined with deep yet narrow shelves, in which much of the museum’s fine collection of works on paper – most notably colonial treasures by such artists as John Glover, Benjamin Duterrau, Thomas Wainewright, Thomas Bock, John Skinner Prout and Louisa Anne Meredith – was snugly housed in dozens of solander boxes.

Other Australian prints and drawings – those as yet unmounted, incompletely documented, or in need of conservation, and later twentieth century works of less easily manageable dimensions – lived in several plan presses, the contents ordered alphabetically by artist’s surname. Yet another press housed the international orphans, material only rarely sought for exhibition or research purposes: various Victorian steel engravings, British modernist lithographs and screen-prints presented by London’s Contemporary Art Society, diplomatic gifts of Japanese woodblock prints or Cambodian temple sculpture rubbings and the like.

However, this comfortable arrangement was not to last. A new institutional building plan required that art staff and collections be relocated to the opposite side of the museum campus, to Orlando Baker’s 1900 Custom House, and although not happy at having to leave our Georgian eyrie on Macquarie Street, we made preparations for the move. Museum registration protocols required that every work in our care be physically and visually checked prior to transfer, and with some 4,000 works on paper in the collection, this presented something of a challenge. Nevertheless, it was a salutary, useful experience for me and my staff to have to eyeball everything, to at least glimpse each and every work, to begin to comprehend the depth and breadth of the museum’s holdings.

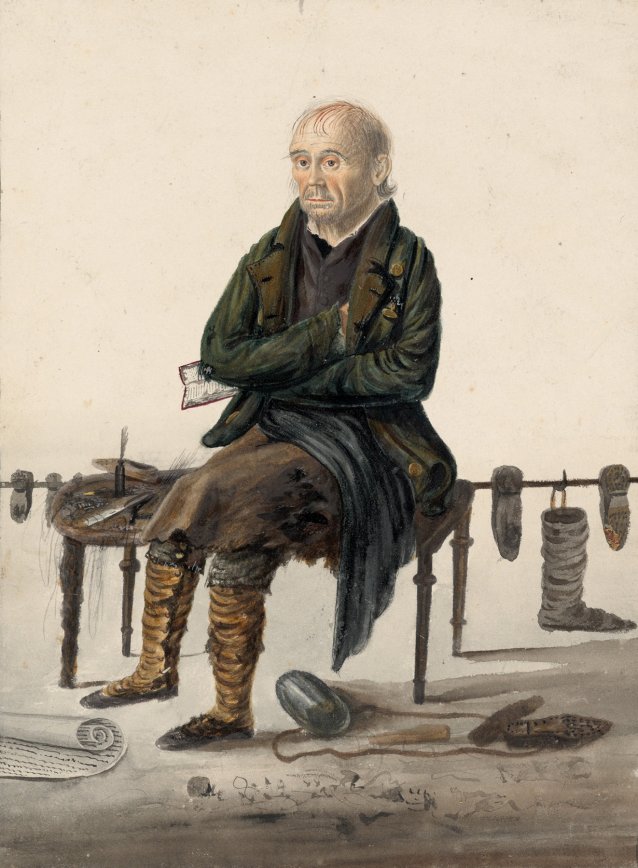

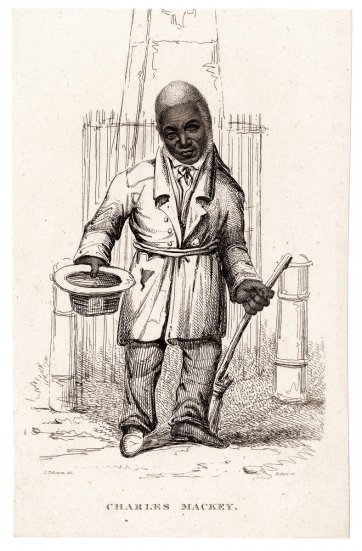

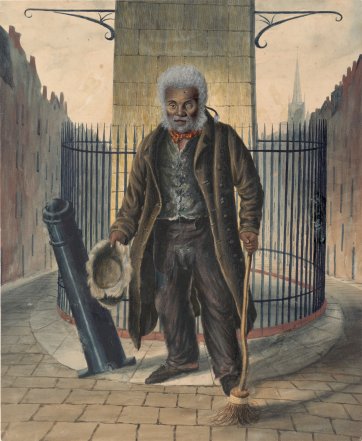

Towards the end of the relocation stocktake we reached the second-bottom drawer of the non-Australian plan press, the drawer lettered ‘U’ – for ‘unknown’. It was there that I first encountered Dempsey’s people, in a folio of fifty-one full-length watercolour portraits of street characters: bellmen, hawkers, beggars, match-sellers, old soldiers, poets, eccentrics, and the physically and mentally disabled.

It was a truly extraordinary cache. Researching the backgrounds of Van Diemen’s Land’s colonial artists had given me a certain familiarity with (and understanding of) the visual culture of Britain in the half-century from 1780 to 1830, and these works were, in my experience, quite unprecedented. They were not the generic images of street traders familiar from the various iterations of The Cries of London, a series that was popular from the seventeenth right through to the twentieth centuries. Nor were they one of those catalogues of typical local or occupational dress that were published in contemporary print portfolios or ‘plate books’. Nor indeed did they resemble in any way the fluent street sketches of the artist to whom they were attributed in the museum’s accession book, the topographical draughtsman George Scharf (1788-1860).

These were identifiable individuals. Indeed, although some works had been trimmed or mounted in such a way as to remove or obscure their inscriptions, forty-five of them were clearly annotated – presumably by the artist – with a date and/or place of execution. Most of them were of the period c. 1823-25, and they came from all over the kingdom, from Scotland to Hampshire, from Devon to East Anglia. Furthermore, fully thirty-one of them were inscribed with the sitter’s name, or at least a nickname. I was looking at real portraits.

Now it is a commonplace of British art history that portraiture was the dominant genre in late Georgian, Regency and early Victorian painting. While ‘history painting’ remained the theoretical apogee of academic art, and while many artists – among them John Glover, JMW Turner and John Constable – maintained and invigorated the tradition of landscape in this period, it was the celebrity image management of Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, Thomas Lawrence, George Romney, John Opie, William Beechey, Thomas Phillips and their ilk that dominated the exhibitions of the Royal Academy. Portraiture was king, even when the sitter wasn’t, and in this politically and economically turbulent period the privilege of pictorial commemoration began to extend down the social and economic scale from royalty, aristocracy and gentry to the ranks of the rapidly-expanding urban middle class. Even so, to have such lowly folk as those in the Hobart set represented in art was an extraordinary rarity, and a gift for practitioners of that ‘history from below’ advocated by the great historian of the English working class, EP Thompson.

So where did they come from? Who had made these portraits of the poor, and why? The provenance offered a few clues. Presented to the TMAG in 1956, the drawings were the gift of Conrad Docker, an expatriate Englishman who had inherited the folio from his uncle Alfred, who was a collector of the nineteenth century colour wood engravings known as Baxter prints. As noted above, Alfred Docker had tentatively attributed the works to George Scharf, and that attribution was conveyed to the museum at the time of the gift. However, Docker’s uncertainty persisted amongst TMAG curators – hence the relegation of the collection to the ‘U’ drawer. It was only when the works were closely examined during the 1996 relocation that one was found to bear the clear inscription ‘J. Dempsey pinxt’.

Who, then, was this Dempsey? Little is known of the artist beyond the bare facts of his birth (in Bath in 1802 or 1803) and his death (in Bristol in 1874), the enthusiastic promotional copy found in his various newspaper advertisements, the itinerant practice indicated by the variety of locations in the Docker folio, and his bankruptcy in 1845. The Docker collection portraits, with their outsize feet and other anatomical solecisms, clearly indicate that he had no formal, academic, classical life-drawing art education. Nor is there any evident training in perspective: some subjects stand before resolutely frontal framing doors and walls; some walk through steeply receding streetscapes of erratically-rendered architecture; but often they have only a pale, partial, tentative background, or none at all. Nevertheless, Dempsey’s faces are truly remarkable, hauntingly real. The details of each sitter’s physiognomy are so carefully and precisely observed and rendered – each cataract-blighted or red-rimmed eye, each gap-toothed mouth, each drinker’s nose, each unshaven chin – that one must assume a considerable capacity to capture likeness, the primary skill required of a portraitist in any market, in any medium, in any age.

John Dempsey was in fact one of an entirely new class of artists. Working across a range of media and price points – in miniature painting, silhouette cutting and even eventually in photography – these entrepreneurial journeyman face-makers supplied the burgeoning lower end of the portrait market during the first half of the nineteenth century. So the figures in the Docker folio – the readily-recognisable faces of the street people of provincial Britain, what he himself advertised as ‘Likenesses of Public Characters’ – were evidently designed to demonstrate the artist’s skill to potential clients as he moved around the country in search of portrait commissions.

My initial intuition concerning the significance of the works was endorsed by several scholars of British art history. Subsequently, I was fortunate enough to secure both a research support grant from the Paul Mellon Centre for British Art and a travel grant from the Gordon Darling Foundation, to pursue the sitters in British libraries and County Record Offices, and I travelled to the UK in 2004.

I could not have hoped for greater success. While I had managed when in Hobart to assemble some information on just one of the sitters, the (now-obscure but then well-known) pastoral poet Robert Bloomfield, the British sources proved extraordinarily rich and productive. Relevant publications, both contemporary and more recent, could be found in the British Library and the National Art Library at the Victoria and Albert Museum, and I also managed to find other pictures of the common people of the Regency period in the British Museum’s vast, almost encyclopaedic collection of portrait prints. Moreover, the British archives included not only the parish records of ‘hatches, matches and dispatches’ (births, marriages and deaths) and data from the censuses of 1811, 1821 and 1831 – all very familiar to family history researchers – but also more recondite sources: obituaries and biographies in regional newspapers; the miscellaneous collectanea of numerous local chroniclers and antiquarians; court reports; public accounts for payments to parish servants such as beadles and bellmen; alms house, workhouse and asylum records – a couple of the sitters had even published small autobiographies.