The Parisian Belle Époque (‘beautiful era’) is arguably one of the most recognisable and lauded periods in the recent history of western civilisation. Its cultural achievements and allure have been canonised in film and literature, and works produced in the period from the late 1800s through to the outbreak of World War One claim prominence in prestigious art collections and auction houses the world over.

Considered a golden age, this period was characterised by extraordinary vitality and optimism, with an unprecedented number of masterpieces in the fields of literature, music, theatre, and visual art produced by a vortex of creative talent. Disseminated through the centrifugal force of Parisian society, it stamped modernity’s imprimatur and was to remain an enduring influence on western society’s cultural landscape and imagination.

Central to this output was the energy and excitement generated through immersion and engagement with society at street level. The sphere of private salons, in which tight and privileged networks of aristocrats, academics, artists and intellectuals mingled throughout the 1800s, became more liberal as the century wore on, and lost pre-eminence in the Belle Époque.

While the private salon was never completely abandoned, the cultural elite moved into the public and highly political realm of the opera, theatres, cabarets, restaurants and cafés, where they mingled with individuals from other levels of society who had sought these venues for the expressive freedom they afforded. As critic Roger Shattuck declared in his illuminating book, The Banquet Years, ‘the organised yet authentic Bohemia of the Chat Noir was a salon stood on its head’.

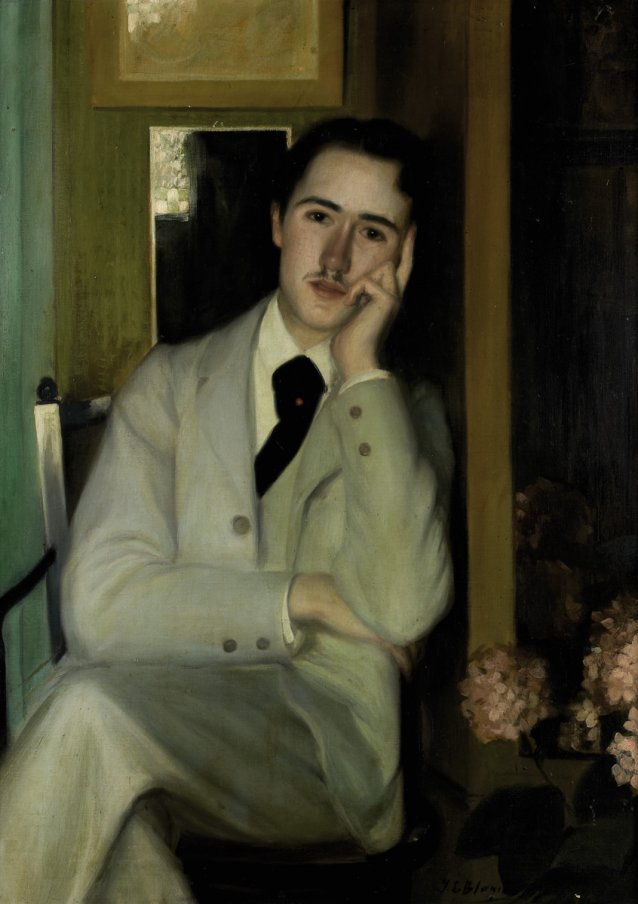

Influencing this move were the newly completed Haussmann boulevards, which had transformed Paris ‘from a village to a stage’. Shattuck credits the boulevards for creating a theatrical aspect to daily life. Evident across all social and cultural strata, this dramatic flair was epitomised by the term boulevardier, invented to describe ‘men whose principal accomplishment was arriving at the proper moment at the proper café’.

The ‘light-opera atmosphere’ of the Parisian Belle Époque was played out in a setting labelled the demimonde, meaning ‘not quite society’ or ‘half world’. Originally coined by playwright Alexandre Dumas (the younger) in 1855, the demimonde was a disparagement for a realm with personages who flouted traditional mores and refined bourgeois values in favour of conspicuously hedonistic lifestyles; this included excessive drinking, flagrant drug use, gambling, profligate spending and sexual escapades. The shadowy demimonde came to public prominence in the carnivalesque luminescence of the Belle Époque’s street-front cabarets and cafés, revealing the goings-on between diverse players: statesmen, intellectuals, actors, artists, writers, musicians, dandies and decadents from the aristocratic classes down.

Holding a pivotal place in Dumas’ demimonde was the demimondaine, the uppermost strata in a tier of women who relied on their looks and sexual services to survive. By the time of the Belle Époque, le demimonde was densely populated with bohemians and the avant-garde, and les demimondaines were a fixture in society.

Known also as mademoiselles les cocottes (hens), or les grandes horizontales, demimondaines were beautiful and cultured kept women; they were courtesans to emperors, princes, statesmen and cultural icons. Many shared the same humble beginnings as women in tiers below – for whom there existed an extensive vocabulary characterising the nature of their venality: lorettes (low-ranking kept women) and grisettes (working women for whom sex occasionally supplemented income) – down to a host of prostitutes accorded derogatory and euphemistic names.

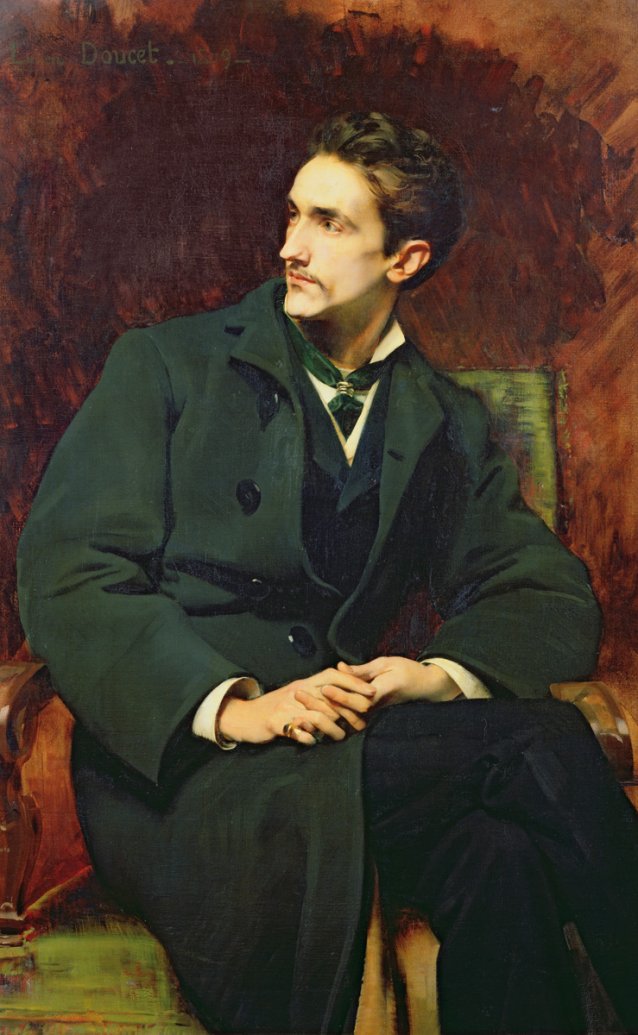

The ranks of the demimondaines were replete with actresses and dancers, the most famous of which was Sara Bernhardt, whose extraordinary talent earned her the status of monstre sacré (sacred monster), a figure elevated beyond public attack despite repeated controversies. Bernhardt lived ‘at the centre of scandal and publicity’, during which time she kept a variety of men infatuated, enthralled and in company. Her likeness – in portraits and in dramatic character – was captured by innumerable artists. Chief among them was her longtime friend, the Orientalist Georges Clairin (1843–1934). His 1876 portrait brilliantly captures her aura: a powerful and alluring presence amidst shimmering satin luxe.

Predominantly, however, these personages were lesser talents, such as Marthe de Florian (born Mathilde Héloïse Beaugiron, 1864–1939), a little-known embroiderer turned actress whose elevated status was only recently discovered. Among the many men reputed to have been de Florian’s lovers were four subsequent prime ministers of France, and a banker from whom she took her adopted name.