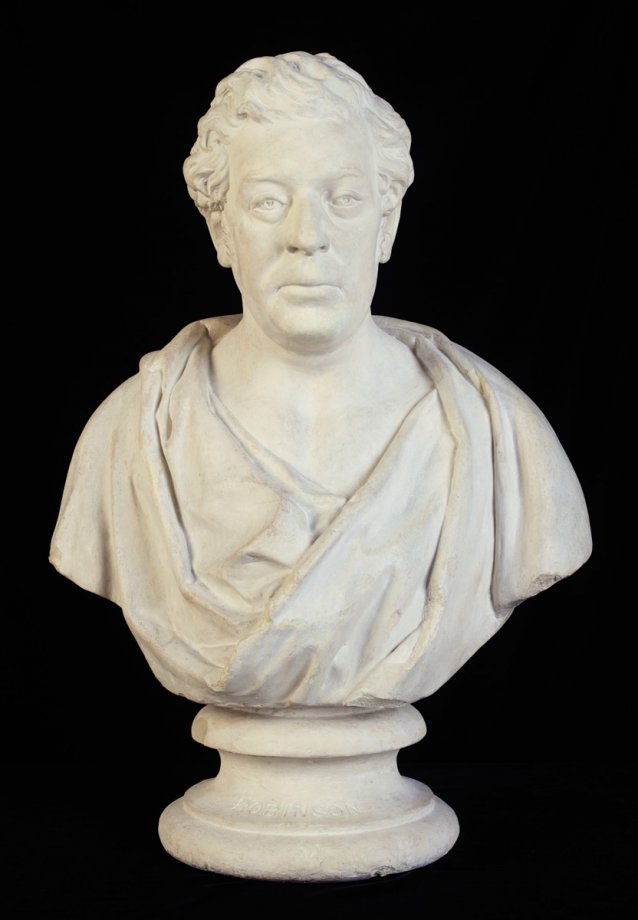

Benjamin Law’s busts of Woorrady, Robinson and Trukanini depict an opposing picture. Law’s tribute to the Friendly Mission presents them as serious figures who have achieved a momentous outcome. Read in order of production, we see both the development of Law’s artistic skill and an evolving narrative on the act of conciliation and the human consequences of the Black War.

Benjamin Law arrived in Hobart with his family on 15 February 1835. We know very little about him. He initially looked to farming to make a living, describing himself as an ‘agriculturalist’. He had come from a family of silversmiths, and, according to his wife’s letters, hoped to use his skill as a sculptor in the colony, only to be told that ‘the colony [was] too young for art’. In one of the few surviving letters written by Law, he said of the colony (to a potential patron living in Britain): ‘I have witnessed the success of others’ and ‘with a small capital we could soon realize a fortune’. We know that he made four busts (Woorrady, Native Chief; GA Robinson, The Pacificator; Trukanini, Wife of Woorrady; and Dr James Ross) and what was described by the Quaker reporter James Backhouse as ‘casts of the faces of the natives of Port Phillip; along with a person named [John] Fawkner, who brought them to Hobart and returned them to their own country again’. After producing these works, Law gave up the life of the artist and became a teacher and shopkeeper; he then ventured to Melbourne and went on to work in the railways, as a clerk, before his death in 1882. Law’s only other work was titled Nightingale, which received several amateur awards in Melbourne art circles. It is unclear from the descriptions if the work was a painting or sculpture.

Law’s busts were relatively cheap and effectively mass-produced. However, because he cast them in white plaster to look like marble (in the case of Robinson), and painted them as either stone, bronze, or black (for Trukanini and Woorrady), the busts maintained a veneer of classical dignity whilst also creating a racial distinction. The Aboriginal busts were a commercial venture based on filling a market niche for mementos of victory through conciliation, with the editor of the Hobart Town Courier calling the bust of Woorrady a ‘very valuable memento’. The busts were popular, but not as mementos; instead the artworks tapped into the emerging market for ethnographic curiosities.

Woorrady was Law’s most commercially successful work. The artist decided a likeness of Woorrady would be a good investment, at a time when he did not have a house or studio. (He moulded Woorrady in a stable). The bust was to provide Law with the capital he needed, with his wife describing the success of the sculpture:

‘[They] are called for not only in all Quarters of the Colony, but are being sent to India, to Sweden, to England, Scotland, and one went last week to Cambridge College, the Gift of the rural Dean of this land the Governor has purchased one and ordered a second he is sending one to the Home Secretary, the Attorney General etc, and indeed all or nearly all the great people, here, he sells these Casts at 4/4 each so that we begin now to be very comfortable indeed.’

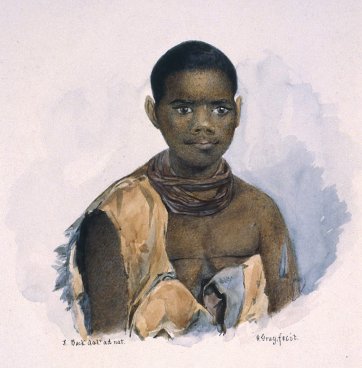

As art historian Mary Mackay has argued, ‘Law’s depiction of Woorrady retains a romantic notion of the “noble savage”’ and ‘the idea of dignified, uncorrupted man is projected in Woorrady’s frontal posture, penetrating eyes and kangaroo skin cloak’. Mackay concluded that at the time Woorrady sat for Law, his garment was the ‘blue serge shirt issued to all the male Aborigines on Flinders Island’. Law therefore presented Woorrady in a noble, primitive, Arcadian mode that was very different to his contemporary state. Nevertheless, Robinson noted that Woorrady ‘was highly pleased with the model’, and liked being portrayed in his traditional costume.

![Truggernana [Trukanini], a native of southern part of V.D. Land Truggernana [Trukanini], a native of southern part of V.D. Land](/files/1/8/5/e/i8535-th.jpg)

![Woureddy [Wurati], a wild native of Brune Island Woureddy [Wurati], a wild native of Brune Island](/files/8/9/0/b/i8536-th.jpg)

![Trucaninny [Trukanini], wife of Woureddy [Wurati] Trucaninny [Trukanini], wife of Woureddy [Wurati]](/files/c/b/d/0/i10110-th.jpg)

![Woureddy [Wurati], an Aboriginal Chief of Van Diemen's Land Woureddy [Wurati], an Aboriginal Chief of Van Diemen's Land](/files/1/8/b/4/i10111-th.jpg)