Real life doesn’t offer a person the opportunity to sell her soul and wade into debauchery, remaining lovely as ever while the face in her portrait sinks and erodes. Outside fables, a portrait stays the same, consoling, taunting or astonishing its ever-degrading sitter with a vision of what she was or seemed, to someone, to be. It was the fate of the Sydney artist Thea Proctor to share sixty-three years of her life with a ravishing picture of herself. Hanging in her flat, it never changed; but her own life might have taken a different course had it never been made, had she never accepted it, or had she never hung it. At most, she should have kept it with her feather fans, tasselled dance cards and amber beads at the bottom of an awkward drawer. Perhaps she would have done better to throw it away.

Thea Proctor, born in Armidale in 1879, learned as much as she felt she could about art in Sydney before leaving for London in 1903. She was to stay there, excepting an interval in 1912–14, until after World War i. When she returned to Sydney forever in 1921, her art and ideas sprang to the front line of contemporary art and design in Australia. Her proclamations on decoration, colour, interior design, flower arrangement, ballet and fashion were published in new journals such as The Home (for which she designed many covers) and Art in Australia, and she had a room to herself in the watershed Burdekin House modern-living expo in 1929. She remained a commanding figure in the Sydney art world almost until her death in 1966. Although she enjoyed a large circle of friends (and adversaries), into her stately old age she lived very frugally in rooms in a 1920s-era building in Darling Point Road, making a slender living from drawing classes, periodic exhibitions at the Macquarie Galleries and commissioned drawings of Eastern Suburbs children. Described by a friend as a ‘breath-taking beauty’, from about 1902 until she died, she was single.

At sixteen, in the mid-1890s, Thea began her art studies at Julian Ashton’s school in King Street, Sydney. Ashton remembered her as a charmer, who readily fell in with the rabble of students. Then there was George Lambert: of all the art schools in all the towns on the eastern seaboard of Australia, he turned up in hers. Lambert had come to Australia from England at thirteen, and had worked as a station hand and jackeroo, shearing, mustering and breaking horses while developing his extraordinary gift for drawing. In Sydney, he was working as a grocer’s clerk while studying at the Ashton school whenever he could. Manly in stature, with steady eyes – characterised as a ‘job-lot Apollo’ by his friend the writer William Beattie – he seems to have been almost literally lustrous. Julian Ashton encouraged his students to take on commercial art, and in 1899, Lambert, Proctor, Sydney Long and Christopher Brennan, amongst others, began contributing to the short-lived Australian Magazine. Many of its stories were illustrated by Lambert, and for some he used Proctor as a model. Lambert shared a studio with Sydney Long in the Ashton school building. In the late 1890s, at about the same time as Long painted his sinuous and fantastical Spirit of the Plains, he managed, somehow – for he lacked polish, and was ‘almost elfish’ – to secure a promise of marriage from the statuesque Thea Proctor. No doubt the reproduction of Spirit of the Plains in the elegant English art journal The Studio encouraged her to believe they could make a go of it.

In the spring of 1900, Lambert married Amy Absell, a photographic retoucher at Falk Studios, and a writer. They shipped out two days later, to subsist on the New South Wales Society of Artists’ Travelling Scholarship in London and Paris. The liaison between Long and Proctor dragged on. Long was surely on the ropes from the start of the round, but the final blow was probably the cruellest: years later, Proctor told a friend that it would have been impossible for her to marry ‘such a bad artist’ as he was. In 1902 she curtailed their understanding; in the autumn of 1903 she left Sydney for a long time, and Sydney Long for good.

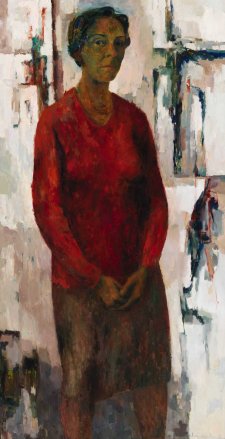

Soon after her arrival in London Thea began art classes in St John’s Wood, but her preparations for the Royal Academy examinations were dashed as she had to take time off on account of eye strain. She never did get to the RA school. Lambert, living with Amy in Shepherds Bush, wasted no time before engaging Thea as a model: a painting of her in a lavishly-smocked blouse, Miss Thea Proctor 1903, became the first of Lambert’s pictures to be accepted by the Royal Academy. In the years to come she would appear quite often in Lambert’s paintings, with and without Amy Lambert and her sons.

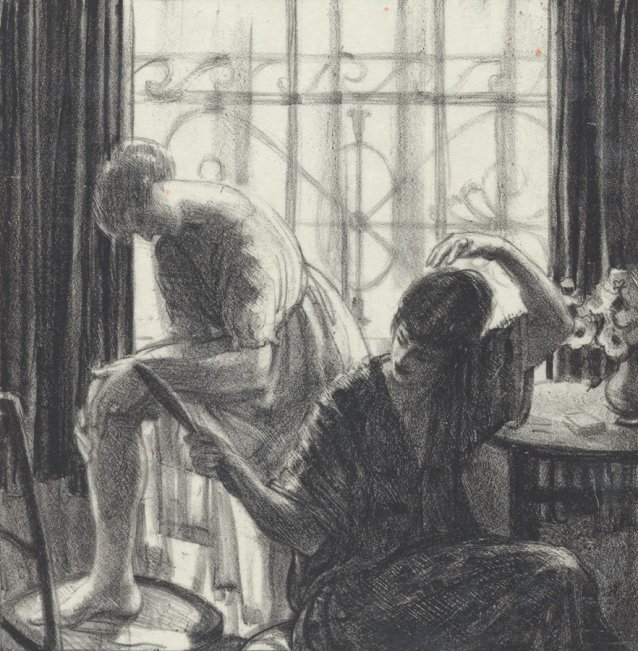

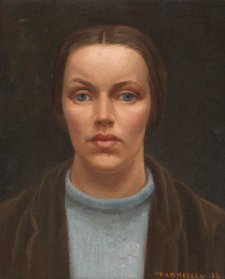

In 1905, George Lambert drew a portrait of Thea Proctor that’s still shocking in its sensuality. It’s clear from the hooded, gentle eyes, the angle of the divinely dimpled chin (the pad of flesh rubbed to light, amongst dark strokes of charcoal) that the artist appraises the sitter from below. The plump flesh of the face invites the viewer’s grasping touch – thumbs on the high cheekbones, fingers laced through the heavy swathes of dark hair caught loosely at the nape. The lit section of neck between high collar and ear lies open to the tongue like a swipe of creamed honey. The cushiony lips, corners benignly upturned, breed imaginings of the sweetest, dirtiest kind. Lambert was a painter of great skill and panache, but his human figures are generally remote, wry actors in the drama of his pictures. To anyone who knows Lambert’s body of work, what’s really remarkable about the charcoal drawing of Thea is the melting warmth it gives off.