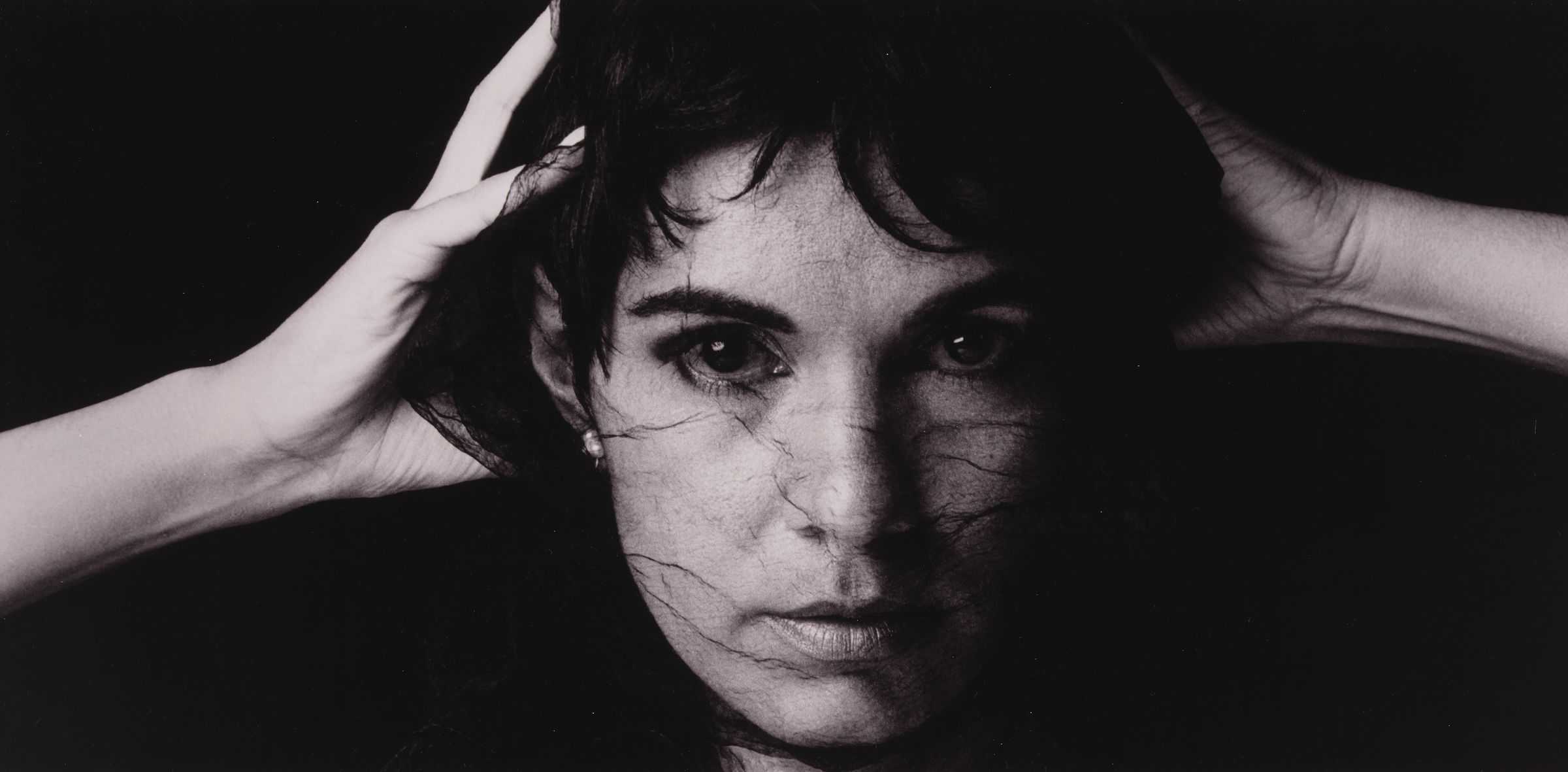

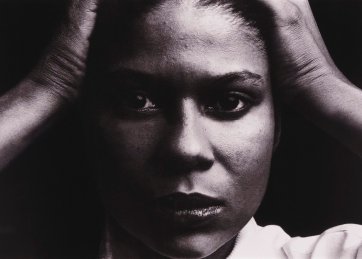

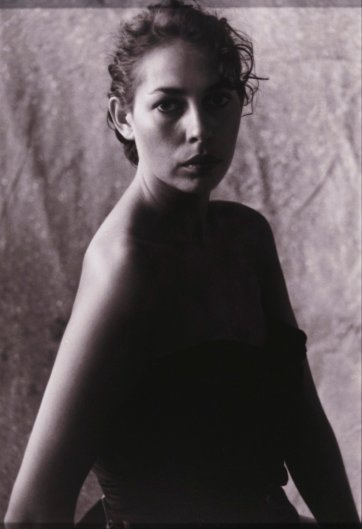

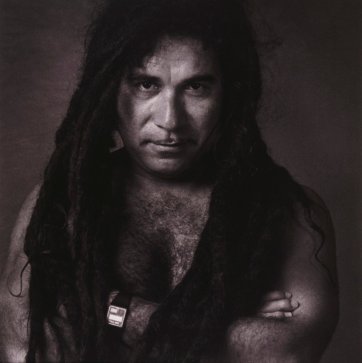

Michael Riley’s fifteen black and white photographic portraits recently acquired by the National Portrait Gallery and displayed in the exhibition Beauty and Strength: Portraits by Michael Riley (22 March – 17 August 2014) were taken by the Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi artist between 1984 and 1990. They are some of his earliest works, representing a pantheon of Aboriginal Australia who forged historical and cultural change and continue to contribute to our culture and politics. These portraits are some of the earliest sympathetic photographic images of Aboriginal people taken by a contemporary Aboriginal artist. For Michael, whose life bridged rural reserves and a cosmopolitan city, they came from a conscious desire to present positive images of a talented activist urban community. In an interview in 1989 he said: ‘I want to get away from the ethnographic image of Aboriginal people in magazines. A lot of images you see of Aboriginal people are like Aboriginal people living in humpies, or drunk on the street or, Aboriginal people marching in protests … I just want to show young Aboriginal people in the cities today; a lot of them are very sophisticated and lot of them very glamorous. A lot of them have been around the world and have an air of sophistication which you don’t see coming across in newspapers and programs. I’m just talking about positive things really, positive images of Aboriginal people.’

Sophisticated and glamorous

by Amanda Rowell, 30 March 2015

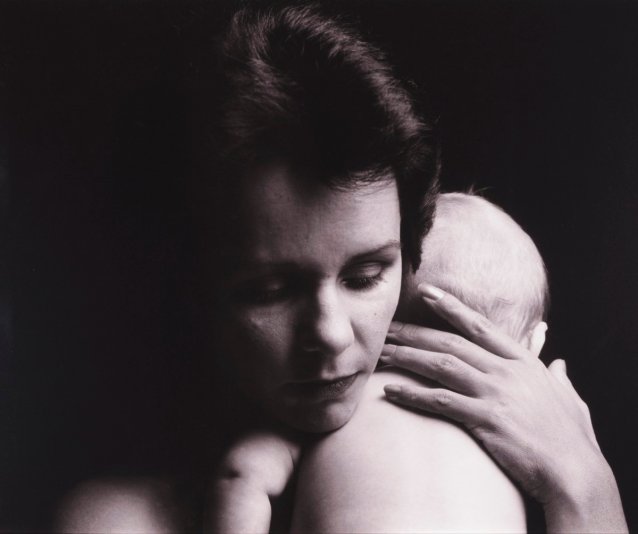

All but one of the portraits are from three exhibitions in Sydney: Koori Art ’84, a groundbreaking exhibition of urban Aboriginal art held at Artspace in 1984; NADOC ’86: Aboriginal and Islander Photographers, the first exhibition by Indigenous photographers at the Aboriginal Artists Gallery in 1986; and Portraits by a Window, Riley’s first solo exhibition, held at Hogarth Galleries in 1990. The portrait of Linda Burney with baby Binni had not previously been exhibited.

The fifteen portraits are a selection from a larger body of work edited for the first exhibition of Michael’s work at The Commercial Gallery in Redfern, Sydney in June 2013. The overriding consideration was to create an exhibition that emphasised the power of the portraits as an historical group. The choice of images was decided between the Anthony ‘Ace’ Bourke, the Hon. Linda Burney and Hetti Perkins (Trustees of the Michael Riley Foundation), Jonathan Jones (who worked closely with Michael, assisting him with the production of his work and continues to have a close association with the Michael Riley Foundation) and me. With the invaluable technical assistance of Richard Crampton who printed most of Michael’s work when he was alive, we arrived at the final group.

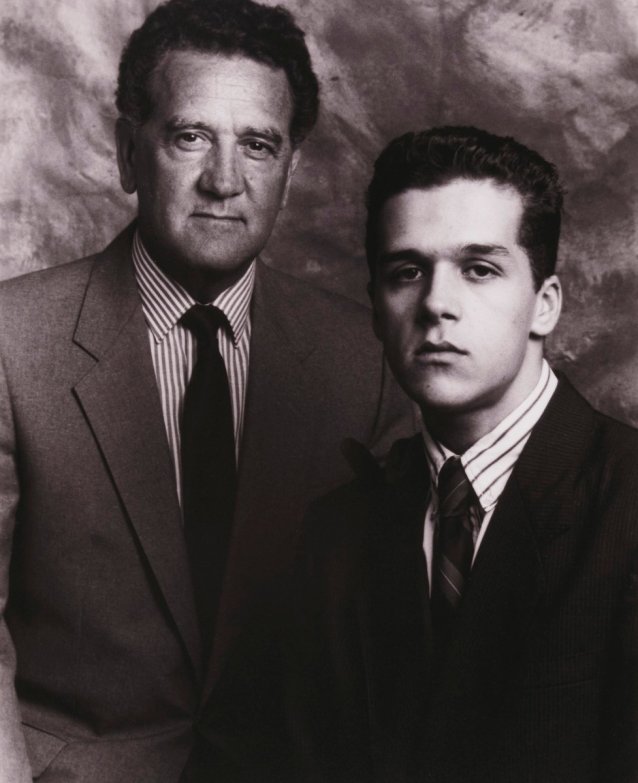

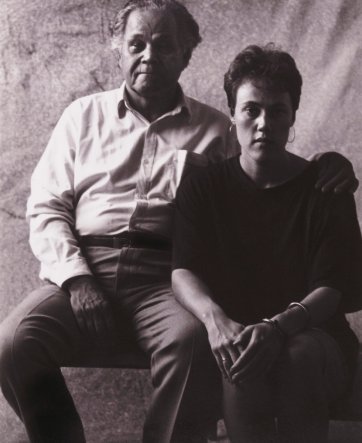

Three generations are represented: Aboriginal leaders, Charles Perkins and Joe Croft, two of the first Aboriginal people to complete a university education in Australia and combat prejudice through anti-racist activism; their children and their children’s peers who benefited from and carried on the legacy of activism of their parents’ generation, in their professions (art, literature, dance, acting, law, politics, cultural administration and academia); and a third generation, babes in the arms of their influential mothers at the time the portraits were taken.

The tender portrait of Linda Burney and baby Binni from 1984 is one of the earliest photographs in the group. Michael lived with Linda when Binni was young. Linda was one of the first Aboriginal women to graduate from a university in Australia and the first Aboriginal person to be admitted to New South Wales Parliament. She is Deputy Leader of the New South Wales Labor Party.

Michael was a brilliant light by any standard and, in an Aboriginal community that comprises such a small percentage of an already small Australian population, his death at the age of forty-four in 2004 was sorely felt. Preparing for the exhibition, I spoke with most of the subjects. Everyone was touched by Michael and was keen to tell stories. Many interesting interconnections between the portraits and Michael’s other works emerged.

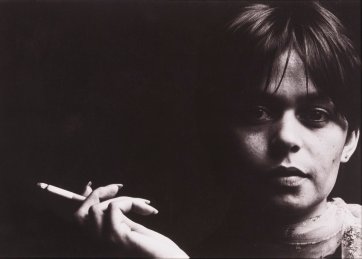

Some of the subjects are now major forces in their professions. Brenda Croft, Djon Mundine and Hetti Perkins are ground-breaking curators nationally and internationally. Croft and Perkins appear in the portraits alongside their influential fathers. Another happy coincidence that emerged from the exhibition is the three glamorous women who shared one wall, artist, curator, arts administrator Avril Quaill, internationally acclaimed artist Tracey Moffatt and two of the dancer and actor Kristina Nehm, had all shared a group house in Glebe around the time the photographs were taken.

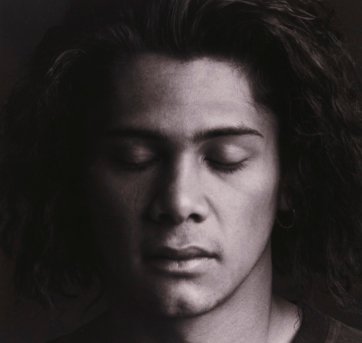

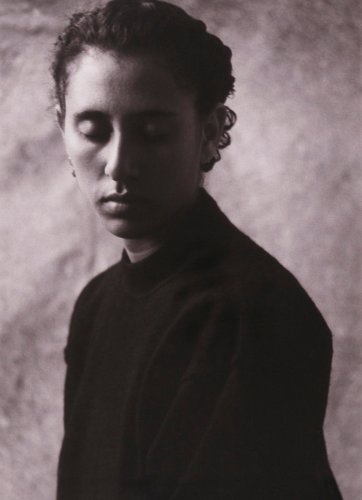

Dancers are a prominent and important element in the group. In 1976, the Aboriginal and Islander Dance Theatre (AIDT) was formed, the first time that Aboriginal people had claimed and controlled an art form on their own terms. A decade later, several of Michael’s subjects were part of the AIDT or the associated NAISDA dance college: Polly (Maria) Cutmore, Telphia Joseph, Kristina Nehm, Delores Scott and Darrell Sibosado. The portraits of the dancers are some of the most sensual of the group, beautiful individuals confident and relaxed before the camera. The wonderful portrait of Delores Scott, daughter of Dr Evelyn Scott, who served as Chairperson of the Aboriginal Council for Reconciliation, is a particularly strong image, universal and timeless.

One of the most fascinating portraits for me is the one of Dorothy (Tudley) Delaney. She is seemingly anachronistic in her dress, hat and crucifix hanging around her neck. At the time her portrait was taken, Dorothy was working at Boomali Aboriginal Artists Co-operative of which Michael was a founding member and remained committed to throughout his life. It was in the back room at Boomali in front of a drop sheet that the Portraits by a Window photographs were taken. Michael had asked Dorothy, who ‘normally wore leggings, runners and a t-shirt because I rode my racing bike to work’, to dress like someone from the 1920s for the photograph. Dorothy had for years been a youth worker at The Settlement, a neighbourhood centre run by the University of Sydney in Chippendale, in drug and alcohol outreach with Aboriginal teenagers on ‘The Block.’

Dorothy, like Michael, was raised as a Christian though Michael was more questioning of the Church and its relation to traditional Aboriginal spirituality. The portrait of Dorothy is, I think, the first time that the cross appears in Michael’s work, a symbol to which he maintained an ambivalent position and which became a recurrent motif in his later work. In 1992, two years after he took Dorothy’s portrait, Michael produced Sacrifice, his first series of conceptual photographs that put Christian imagery side-by-side with images of death and drug use in the context of traditional spirituality. Dorothy’s portrait now appears like an encapsulation of and pre-curser to the deeper themes of the later series.

The group of portraits is greater than the sum of its parts in its generational force and the combined legacy of these individuals. Michael went on to produce two more important portrait series.

In 1991, he photographed the community in Moree where he grew up, his mother’s people. These portraits, exhibited in London at the time, were the first to give Michael international recognition. Then, in 1998, he photographed the community from his father’s birthplace of Talbragar Reserve near Dubbo. These three groups of portraits are extraordinary documents of their time, bridging urban and rural Aboriginal communities, full of Michael’s watchfulness for beauty and intelligence and deeply political in their aspiration for his people.

Related people

Related information

Beauty and strength

Portraits by Michael Riley

Previous exhibition, 2014Influential Indigenous Australian artist Michael Riley (1960 - 2004) created these portrait photographs between 1984 and 1990 - they stand as an intricately connected group portrait of the vibrant urban-based Indigenous arts community in Sydney's inner-west at a formative moment.

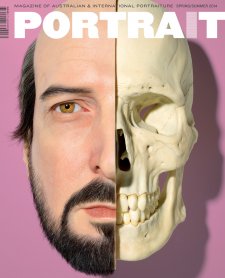

Portrait 47, Spring/Summer 2014

Magazine

This issue features Michael Riley, TextaQueen, Thea Proctor, Jean Appleton, In the flesh, digital identity and more.

Pen power

Magazine article by Jane Raffan

Politics and personae in the portraiture of TextaQueen by Jane Raffan.