It seems to have become axiomatic to understand that the progress of modern art in Australia owes a lot to certain women. The names are familiar to us: Margaret Preston, Thea Proctor, Grace Cossington Smith, Grace Crowley et al. Women born in the decades around the turn of the century and educated by forward-thinking teachers at art schools in London and Paris. Those who, irrespective of the expectation that nice, respectable girls should abandon ideas of any profession – let alone one as potentially compromising as art – determined on careers and independence, either eschewing marriage and motherhood or opting for partners who were accepting of less conventional arrangements. Artists that hung on in quiet dedication to their trade in spite of the dismissal of their output as ‘feminine’ or ‘decorative’, and in defiance of art-world indifference to and occasional vitriol against their work in a climate when the most conservative of their critics famously used words like ‘degenerate’ and ‘addled’ to describe modern art. The women artists now highly esteemed within Australian art history, but who were octogenarians before it occurred to public galleries to mount retrospectives of their work.

In good company

by Joanna Gilmour, 30 March 2015

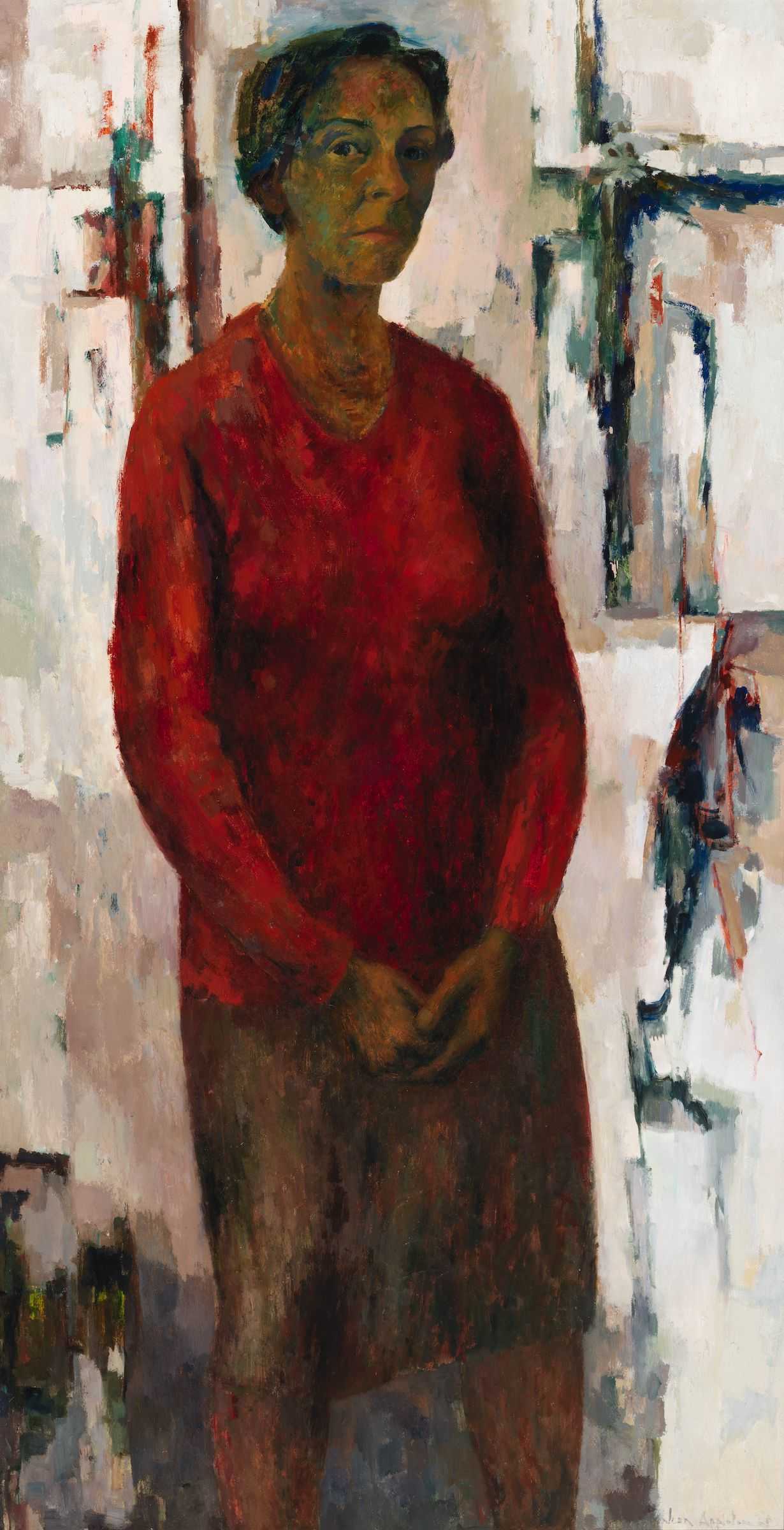

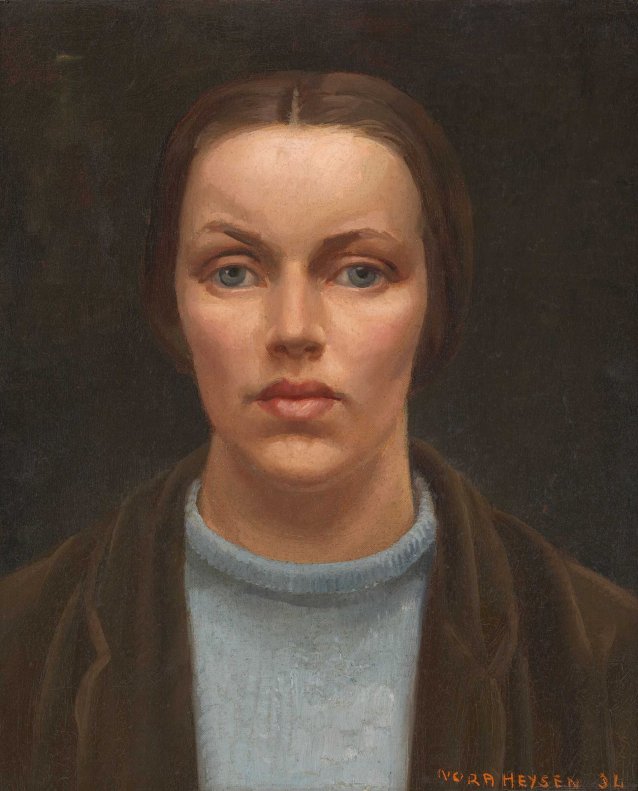

As art historian Jane Hylton explained in her 2000 exhibition catalogue Modern Australian Women: ‘Working in major population centres in Australia or communicating from Europe to friends and relatives at home, these women made a contribution which resulted in [the interwar decades] becoming crucial to the history of Australian art.’ Fittingly, the National Portrait Gallery’s collection includes self portraits by a number of the big guns of the group, executed in the styles by which their subjects claimed a distinct and visible place for themselves in the Australian art canon. Take Cossington Smith’s shimmering 1948 portrait of herself at her easel. One of modernism’s foremost local exponents and credited with the first post-impressionist picture exhibited in Australia (The sock knitter, painted in 1915), Cossington Smith’s self portrait is ‘painted in squares’ – her method, as she once explained, of putting ‘light into colour’: ‘Just to put colour onto the surface in a flat way, I feel, it gives it a dead look’. Given her situation at the forefront of drawing and printmaking, and her role in elevating the status of both, there’s little wonder that Thea Proctor executed her only known self portrait in lithograph form, an image which also suggests the stylishness for which she was well known. And in Nora Heysen’s self portrait, painted during her student days in London, we see the artist perfecting her immense skill as a portraitist, a skill developed so as to distinguish her work from that of her revered, landscape painter father. As Heysen recalled in 1994, ‘I wanted at that time to get away from my father’s subject matter, so I turned to painting faces and painting myself … to get right away.’ Added to Gallery’s collection in 2012 and 2013 are two self portraits – one a study for the other – by Heysen’s friend and exact contemporary, Jean Appleton (1911–2003).

Though she is less likely to come to mind when listing the occupants of the Australian modernist pantheon, Jean Appleton’s history reads much like that of the women artists most immediately identified with it. The comfortable urban upbringing; the periods of study and travel abroad; and the settling back in Australia to pursue distinguished careers characterised by resolve, inventiveness, curiosity, longevity and (for many years) relative obscurity. Born in Sydney in 1911, Appleton stated in an oral history recorded in 1962 that she couldn’t remember a time when she didn’t draw and that as a child she was constantly in strife for the drawings she had a habit of adding to the back pages of her arithmetic books. Having gained some rudimentary instruction in art at school, she convinced her parents – who thought that art was all very well as a hobby, but nothing else – to allow her to enrol at East Sydney Technical College. Appleton later said that she found her initial years as a student something of a disappointment, the teaching unstimulating and overly academic, just as Heysen had found her training at the School of Fine Arts in Adelaide in the 1920s. Things changed for Appleton, however, with the arrival of teachers such as the Slade School-trained Frederick Britton; and Douglas Dundas, the recipient of a Society of Artists scholarship who took up a position at East Sydney Technical College on his return from Europe in 1931. Both ‘brought new life into the school’, encouraging Appleton to continue on until the completion of a diploma in drawing and illustration in 1932. ‘Being uncertain what to do next and feeling that it was necessary to earn some money’, Appleton and her friend and East Sydney colleague, Dorothy Thornhill, proceeded to set themselves up in a studio near Circular Quay, right in the thick of what was then Sydney’s creative precinct. As Appleton recalled of Circular Quay at this time: ‘You could go out of your studio at lunchtime to buy a threepenny pie from Miss Bishop’s and meet half of Sydney’s art world, either buying pies or heading for Fiaschi’s wine bar or Mockbell’s coffee shop’. In her Dalley Street studio, Appleton produced fabric designs and ran a weekly sketch club, continuing her tuition in drawing and painting with occasional classes at Grace Crowley and Rah Fizelle’s atelier, and exhibiting works in the Society of Artists’ exhibitions from 1932.

During this time, especially after seeing the ‘splendid facsimiles’ of works by Cezanne and others displayed at Anthony Hordern’s emporium in early 1934, the idea of travel to Europe and the prospect of seeing post-impressionist paintings in the flesh took hold. Her father’s passing in 1935 meant that she didn’t have to contend further with traditional, paternal disapproval of her desire to live and study overseas and, helped by the good word of a great-aunt with feminist leanings, Appleton was finally able to embark for London. She left Australia in 1936. Having found herself suitable digs, she enrolled at the Westminster School – ‘quite the most alive and exciting school at that time’ – where she studied under teachers including Mark Gertler, Bernard Meninsky and George Elmslie Owen, completing during her student years what are considered some of Australia’s first cubist paintings, such as Still Life and Painting IX (both 1937). In London, she fell in with a group of other Australian artists including Donald Friend, William Dobell, Eric Wilson (whom she married in 1943) and Arthur Murch, the latter enlisting her to the team that worked on a mural and exhibit for the Wool Secretariat pavilion at the British Empire Exhibition in Glasgow in 1938. In between study and work, when she had the money, she travelled, in particular to Paris . ‘I was able to see things that I could never have dreamed about before then’, Appleton later said – things such as Picasso’s Guernica when it was first shown at the Paris International Exposition in 1937; and the exhibition celebrating the 1939 centenary of Cezanne’s birth. With World War ii in the offing, Appleton returned to Sydney in May 1939, working briefly as an art teacher at the Church of England Girls’ Grammar School in Canberra and, during the war, with an occupational therapy centre in Sydney.

In the meantime, she had begun contributing again to the annual Society of Artists exhibitions – alongside Friend, Dobell, Cossington Smith, Roland Wakelin and other modernists – and to those staged by the Contemporary Group, which had been formed by Thea Proctor and George Lambert in the mid-1920s. Here, her story perhaps begins to vary with those of the women a generation ahead of her in that, rather than working against a critical grain which largely favoured tradition in painting, Appleton found a climate more conducive to modern and non-figurative styles. Whereas it has previously been typical to think of 1930s and 40s Australia as a cultural and artistic backwater, recent scholarship has pointed to the existence of a more sophisticated scene, shaped by the influence of those who, first hand or otherwise, had experienced the latest thinking in the galleries and art schools of Europe. Reviewing Appleton’s first solo exhibition in September 1940, the Sydney Morning Herald’s art critic reminded any sceptics that modern ways of seeing might in fact be a good thing. ‘During the past year or two’, the reviewer stated,

‘a number of Australian artists who have been studying or working in Europe have returned to their native land. Australian art is the gainer thereby. These painters, who come fresh from contact with the great contemporary movements, enliven the local scene with something new and vital’. In her 1998 essay on Appleton’s life, art historian Christine France has described this period as a ‘golden age’, when many Australian artists coming back from overseas ‘became involved in teaching, and broke through the rigid academic training which had long restricted the development of ideas in the visual arts.’

Perhaps most notably, Appleton returned in the late 1930s to a local art scene that had become considerably less hostile to modernism. Bodies like the Contemporary Group and Melbourne’s Contemporary Art Society, early members of which included Albert Tucker, Sidney Nolan and Arthur Boyd, vigorously encouraged and defended innovation, experimentation and the avant garde. Exhibitions such as the Herald Exhibition of French and British Contemporary Art, which was shown initially in Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney in late 1939 and later travelled to venues in Tasmania and Queensland, demonstrate also that there was broader interest rather than revulsion in the work of modern masters. As another nameless reviewer had observed in 1934: ‘Except among a few ultra-conservatives, unreasoning hostility to overseas work is a thing of the past. The time has arrived when this work can be studied calmly and quietly, and its essential values gradually absorbed.’ Greatly in Appleton’s favour also was her being picked up by the Macquarie Galleries in 1940. Established by John Young and Basil Burdett in 1925, by the 1940s the gallery was under the direction of two women, Treania Smith and Lucy Swanton, who helped consolidate its reputation as Sydney’s primary site for the exposure and advocacy of modern art. It was particularly known also for showing the work of women artists, the likes of Cossington Smith, Crowley, Proctor, Margaret Preston, Margaret Olley and Jean Bellette among those it represented.

In the 1940s, following her inaugural solo exhibition and having contended with the loss of one brother and her first husband, Appleton continued with teaching (at the Julian Ashton Art School and at East Sydney) and saw her works begin to be acquired for public collections, all the while developing a sustained practice and a deepening interest in colour, light and abstraction. With her second husband, the artist Tom Green (whom she married in 1952) and their daughter, Elisabeth, Appleton moved to the Southern Highlands town of Moss Vale in the early 1970s. Like Cossington Smith, whom she had often joined for painting outings in the bushland near their northern Sydney homes in the 50s and 60s, in the second half of her career Appleton became increasingly focussed on her own surroundings and ‘preoccupied with light, not a source of light but a light playing over the whole area’. This is a characteristic demonstrated by the luminous still lifes and interiors she painted from the 1970s onwards and also in her self portrait of 1965. The inaugural winner of the Portia Geach Memorial Award – established in honour of artist and feminist Geach’s long campaign for equal recognition for women in art prizes and exhibitions – Appleton’s self portrait is constructed in dabs and wide brushstrokes, the face delineated in contrasting tones, ‘the light invading the shadows rather than defining their edges’, and the figure backgrounded in a linear abstract design not unlike those found in Appleton’s interiors, still lifes and landscapes of the same period. Both the self portrait and the study for it have been held in private collections for some years. In 2012, Laurie Curley OAM and his wife Robyn, made a gift to the National Portrait Gallery of the study. A collector of Appleton’s work, Mr Curley had some years previously encouraged his friend, Nicolaas Van Der Waarden to purchase the finished work, which entered the Gallery’s collection in accordance with the late Mr Van Der Waarden’s wishes in 2013.

As was so for her friends Cossington Smith and Heysen, it wasn’t until Appleton was in her eighties that her sixty-year career was honoured with a survey exhibition at a public gallery (in 1996). The addition of Appleton’s self portrait to the National Portrait Gallery’s collection might go some way, at least, to reinforcing her place within that group of women who helped shape the direction of Australian painting in the twentieth century, and whose contributions are no less significant for being unassuming, or too long unsung.

Related people

Related information

Portrait 47, Spring/Summer 2014

Magazine

This issue features Michael Riley, TextaQueen, Thea Proctor, Jean Appleton, In the flesh, digital identity and more.

The Gallery

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!

Support your Portrait Gallery

We depend on your support to keep creating our programs, exhibitions, publications and building the amazing portrait collection!