In 2005 the Chinese conceptual artist Song Dong persuaded his mother, Zhao Xiangyuan, to partner with him and create the monumental work Waste Not. Consisting of 10,000 domestic objects collected by the artist’s mother over five decades, Waste Not reflects Zhao Xiangyuan’s experiences as a daughter, wife, mother and grandmother during a turbulent period of Chinese history. Married for over four decades, Zhao Xiangyuan and her husband, Song Shiping, survived a life of poverty and hardship by adhering to the mantra wu jin qu long – literally translated as waste not. This meant that everything which could be used, would be used, for as long as possible.

Following Song Shiping’s unexpected death in 2002, Zhao Xiangyuan became withdrawn and isolated, collecting objects that were no longer needed and refusing to throw anything away. In an attempt to free her from this obsession yet preserve his parent’s dignity, Song Dong suggested he and Zhao Xiangyuan work together to turn these objects into an artwork, creating a space for Zhao Xiangyuan to reconnect with the world and ‘put her memories and history in order’.

The objects included in Waste Not embody Zhao Xiangyuan’s long-held anxieties for being able to provide for her family. Her preparedness for ‘making do’ on governmentissued supplies of fabric, food and toiletries developed when she was a young woman. In 1953 Zhao Xiangyuan’s father was declared a spy and imprisoned for seven years. By bartering their clothes and jewellery for grain and undertaking basic tailoring work, Zhao Xiangyuan and her mother managed to survive without his income. However, these years of hardship instilled in Zhao Xiangyuan a dogmatic approach to saving pieces of soap, scraps of cloth and pairs of shoes in anticipation that one day they might be useful for her own children and grandchildren. As circumstances changed and the living conditions of the family improved it became clear to Song Dong that Zhao Xiangyuan’s focus remained on the uncertainty of the future. Unable to convince her to part with these objects they came to represent a vast generation gap between mother and son.

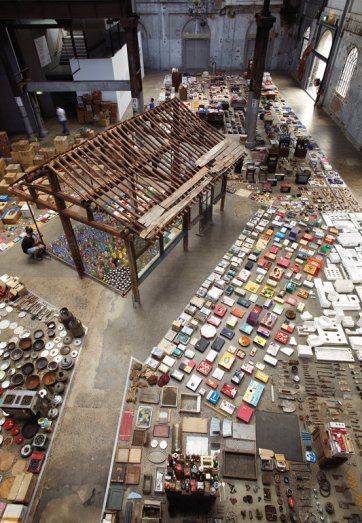

Although you never see an image of the family, each object in Waste Not provides us with a clue to building a portrait of Zhao Xiangyuan and her world. We imagine her day to day life and activities through the neatly arranged items of crockery and cutlery, plastic bags carefully folded into triangles, bundles of twine, stacks of birdcages, boxes of medicines, empty tubes of toothpaste, piles of books, and folded items of clothing that fill over 1,000 square metres of floor-space. When viewed from above the installation resembles a vast urban sprawl that has been categorised into thematic districts of eat, wear, live and use. Accompanied by Zhao Xiangyuan’s memoirs and Song Dong’s commentary these humble items are personified. Social histories and family stories are interwoven to represent tales of loss and love, hardship and resilience.

The conceptual heart of the work is a wooden structure that was once part of the family home in suburban Beijing. Supported by scaffold and held together by the original pegs and pins used to build the house over a century ago, Zhao Xiangyuan insisted the structure be saved when the family renovated the site in the 1990s. Each time Waste Not is exhibited this house is the first thing to be positioned and installed. Over a number of days it is painstakingly unpacked, laid out and reassembled. Transformed by its context into an art object, this structure reminds us of the labour and care involved in maintaining a family home.

Other objects bear scars, like the kitchen utensils. Broken and repaired, they are lovingly bound together with wire, tape and ribbon. A proud row of seventeen shabby chairs salvaged by Song Shiping and Zhao Xiangyuan greets the visitor on entry. Over the years these chairs were used as a bed-base for guests and a makeshift table for the washing machine. Birdcages made by Song Shiping’s father are stacked atop each other, a memory of little birds kept in the courtyard as family pets. Neatly arranged fast-food containers used to feed the twenty-two neighbourhood stray cats sit alongside bundles of fabric which were saved for making clothes, and the empty toothpaste tubes whose lids became perfect buttons for children’s shirts. Song Dong recalls Zhao Xiangyuan’s joy in seeing these materials finally achieve their purpose as she said to him, ‘You see that keeping them was still useful!’

Arranged in a neat square are 256 pairs of shoes. For Zhao Xiangyuan, shoes symbolised risk, the oppression of the Red Guard, and the sacrifice made by her mother to provide for her. Included are hand-sewn cotton-soled shoes made by Zhao Xiangyuan, reinforced with cardboard and bamboo when they were worn through, small black shoes which had belonged to Zhao Xiangyuan’s mother (whose feet were bound to keep them small and dainty), and baby booties worn by Song Hui and Song Dong. Missing from the group is a pair of wedge sandals which ‘fell victim to the Cultural Revolution’. Worried they were too Western in style, Song Shiping tied a rock to them and threw them in the river. He had witnessed first-hand the unprovoked beatings on civilians whose clothes were interpreted as being counter-revolutionary.

Following his mother’s death in 2008, Song Dong has continued to install Waste Not around the world with his sister Song Hui, his wife Yin Xiuzhen and their daughter Song Errui. For Song Dong the act of making this work is integral to its meaning. Working with a team of local artists and installers they reconfigure the installation and share stories that cross cultures and generations, touching upon the immensurable bond between parents and children. They rebuild this monument to Zhao Xiangyuan and her life, a multifaceted portrait where she is both visible and invisible, yet always present. On the exterior of the building is a neon message from Song Dong to his parents that says, ‘Dad And Mum, Don’t Worry About Us, We Are All Well’. It is important for this message to face the sky, so his parents can read it from heaven. The optimism in this note suggests that as much as it is about grief and memory, Waste Not is also about the continuum of life.