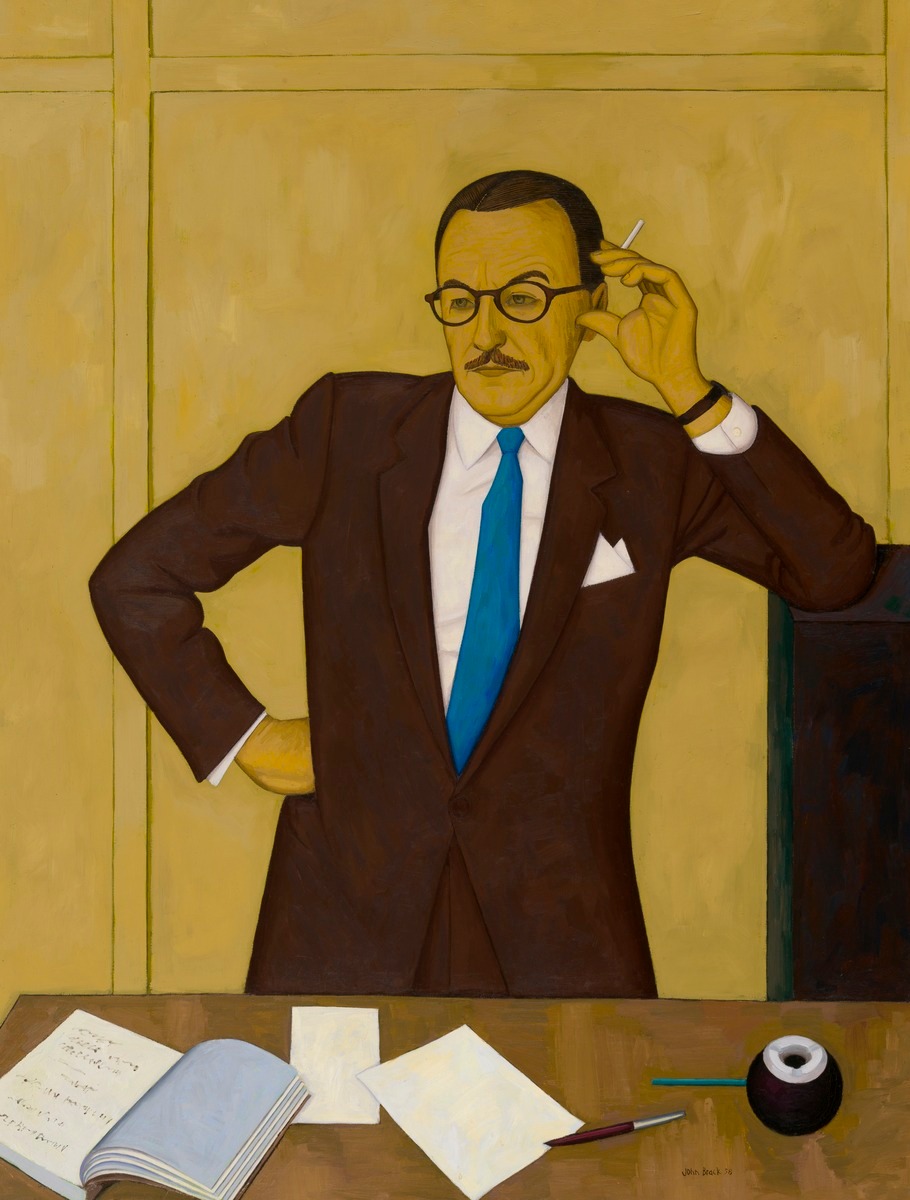

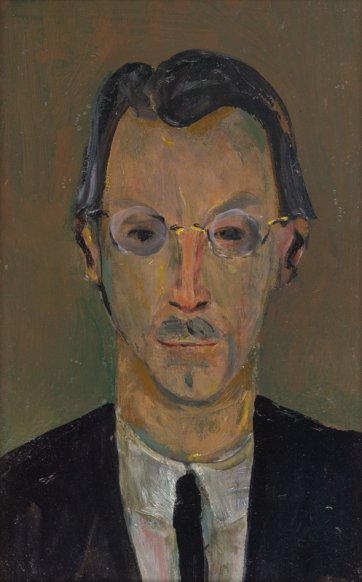

My recollections are – and they are only from memories of conversations as I was a young boy at the time – the portrait of my father was painted as a result of an agreement between him and John Brack. It was to demonstrate what may be expected from a commissioned Brack portrait.

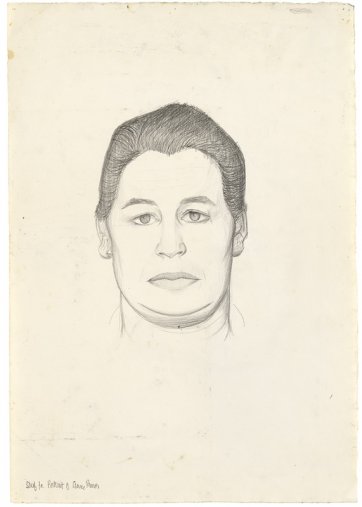

A subsequent commission was that of my mother, Anne. The portrait did not seem to be hung for very long in our home. I have a memory of the picture being of Anne seated on a floral covered sofa with her left arm outstretched along the back of the sofa and her head positioned in a slight profile, also looking left. Anne did not like the painting and she said her mother burst into tears when it was shown to her. On other occasions when it saw the light of day it did seem to cause a lot of family disturbance. It seemed my mother did not want the portrait to exist, nor for her to be remembered by this image from such a prominent artist as John Brack.

Her next action with the painting is one I have a very strong recollection of. It was a Saturday morning and the day was bathed in bright daylight. Our family gathered around the old 44 gallon burning barrel in the backyard. A fire was lit inside the drum and Anne placed the Brack portrait into the barrel and thus the portrait was burnt.

Very little seemed to happen for some time afterwards but as the decades passed and both the artist and sitter grew in prominence the action seemed to receive more attention. From time to time it does crop up in conversation within the art world, and its destruction was documented in Sasha Grishin’s catalogue raisonne of John Brack’s work.

Helen Brack and I have always had an amicable relationship, actually, better than that, and I am full of admiration for Helen’s integrity and the way in which she holds proper art on high, and discards without the slightest qualm the rest. In correspondence in September last year Helen reminded me why John’s portrait of Tam was in the their collection. Helen wrote, ‘Tam asked John to do the portrait and John assumed it to be a commission. I asked what the agreed priced was and John said that it would be the normal commission price. I insisted on an agreement with Tam about this but John said Tam understood the financial part of the deal and would I not interfere; so I let it be, and didn’t think about it any more. Tam was delighted with his portrait and formally commissioned the one of Anne. When the payment time came, John assumed there were two commissions, but Tam said that only Anne’s had been commissioned; his portrait, Tam had assumed that John understood, was a bonus for all the sales that had been made for John. John was outraged and said he did not owe Tam a bonus, and if Tam wouldn’t pay for his portrait he wouldn’t get it. Both stared down each other, and Tam paid for Anne’s portrait and got it, didn’t pay for his portrait, so didn’t get it. Really, just a misunderstanding on both sides. John should have done what I thought right, but in that case there would not have been a portrait of Tam.’

The 50th anniversary of Australian Galleries was celebrated in 2006. In preparation for the anniversary exhibition I rang Helen to see if she would kindly loan the portrait of my father to hang in the celebration exhibition. Helen graciously agreed to the loan the Tam Purves portrait. When I arrived to collect the portrait for the anniversary exhibition she invited me to come inside and just chat for a little while. We talked about all sorts of things and then I decided for the first time that I would raise the subject of Anne’s portrait. The outcome was that both John and Helen were forever surprised by Anne’s actions and they didn’t understand, as they thought it was a good painting. Helen also revealed that John was very upset when he discovered that the portrait had been burnt, so much so that when George Mora, John’s dealer, died John had said to Helen, ‘I would love to go to Stuart but I can’t go to a gallery that has burnt my painting’. Of course, I would have been honoured to have represented John’s work. He had held one very important exhibition at Australian Galleries, being his nudes in 1957, and how wonderful it would have been if his final exhibitions had been with us, but I understand his emotions relating to the decision not to hang his work on our walls.

John Brack died in 1999, the same year as Arthur Boyd and as it turns out my mother as well. I have often thought that this elderly group of most interesting people may have subconsciously chosen not to live into the next century. I went to John's funeral where Helen gave the most amazing eulogy, her clear intelligence shone out. Amongst her profound words she praised my parents’ involvement with John in the early years and how important it was for them all. I was very moved at her warm words for Anne, knowing what I knew. The astonishing thing is that when I went into John’s funeral my mother, although in hospital quite unwell, was alive. Immediately after Brack’s service I received a phone call informing me of my mother’s death. I thought how extraordinary this timing was and that my mother died almost certainly at the moment that she was being praised by Helen.

In 2002 my brother Toby, sister Caroline and I gave the other portraits of our parents to the National Gallery of Victoria. They were a series of four canvases of Anne by Arthur Boyd and Anne by Brian Dunlop. The drawings and studies of Tam by Brack for the portrait are now in the National Portrait Gallery Collection. At the same time Lyn Williams donated an oil painting of Tam by Fred Williams.

The entire Purves family, especially my sister Caroline and I, are thrilled and delighted that the portrait of our father, Tam Purves, painted by John Brack, has made its way to the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra. I am very much looking forward to viewing again the portrait of my father.