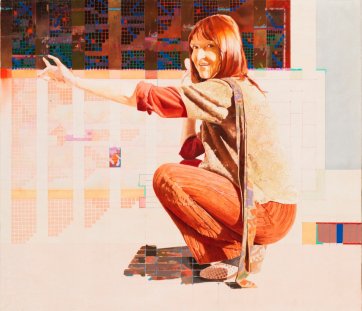

When Fay Bottrell was painted by David Campbell, she was fifty-four and he was twenty-nine. Hers was the third, and last, portrait he ever painted. Now, she’s eighty-five, and it’s nearly thirty years since he died.

David Campbell, born in 1952, was a student at Erina High school when he set his gentle heart on becoming an artist. Moving from the New South Wales central coast to Sydney, he studied from 1973 to 1977 at the Alexander Mackie College of Advanced Education. Painting and playing his flute were all he wanted to do, although he worked as a cleaner, a tennis coach, an assistant in an aged care facility and a waiter at Tattersalls. In the late 1970s and early 1980s he lived and worked in the loft of a building on the corner of Pitt and Park streets (above the current McDonalds franchise). Once known as Poverty Point, according to Sydney historian Shirley Fitzgerald the intersection had long been a gathering place for ‘clowns, contortionists, jugglers and boxers’ as well as poets, musicians and thespians resting between jobs.

Given this milieu, it is fitting that Campbell’s first portrait subject was the poet, performer and promoter Adrian Rawlins; yet it’s salutary that no one knows how they met. When a person dies young, having made only a start on carving out an autonomous personality, those bereaved are often left wondering forever what their loved one was like; how they appeared, and to whom, as an independent adult. Much of what we know of another person comes from stories that they tell after events, as older people eager to rehearse and rehash what have come to seem like the defining moments of their lives. The historical record on Campbell comes down to a folder of press clippings, photos and academic transcripts preserved by his sister, Elizabeth. Probably, nothing more will ever be known of him.

About Adrian Rawlins, there’s a superabundance of information. Born in 1939, he grew up in a Jewish household in Caulfield and St Kilda. He was taught for a while by the artist Danila Vassilieff, and studied theatre with Frank Thring. In the 1950s he began to write about music and promoted the band the Red Onions, who evolved into the Loved Ones. From 1960 to 1961 he presented a weekly poetry and jazz session on radio. Living in the back of a derelict house on St Kilda road, in 1965 and 1966 he ran the Fat Black Pussycat as a contemporary and experimental jazz venue. During this period, he appeared in the pop culture documentary Approximately Panther, and attached himself to Bob Dylan on his 1966 Australian tour; in 1994, his collection of essays Bob Dylan through the looking glass was published.

In the late 1960s Rawlins moved to Sydney, where he fell under the spell of the mystic poet and musician Nevil Drury and became a pioneering hippy, follower of the Vedantic/Sufi/ Zoroastrian/Christian holy man and international celebrity, Meher Baba. In 1968 he is said to have been involved in some way with one of the country’s first counter-cultural zines, Chaos, typed and printed on a kind of butcher’s paper, featuring undulating hand-drawn advertisements for shops such as The Fatal Glass of Beer with its ‘Posters, Incense, Buttons, Beads and Jewellery’ and The Pot Hole in Barcom Avenue, Paddington, offering not only buttons and beads but ‘Way-Out Summer Gear, and Psychedelic Things’. They were the kinds of places where the twenty-year old artist/writer who sought through the classifieds a ‘GIRL, gently swinging but sensitive’ might have found her. The first issue of Chaos featured a condensed interview with Timothy Leary, an article advocating the legalisation of marijuana (on the reasonable basis that tokers only went on to use heroin because the same dealers offered both) and a stilluseful explanation of psychedelia: ‘Total involvement is psychedelic in the sense that an environment that is uniformly aimed at all the senses will produce definite changes in consciousness rather than the diffuse mental processed arising from different or partial stimulations of each sense.’ By 1968-69 Rawlins was mentoring the New Zealand band The La De Das, encouraging them to record an ambitious concept album built around the Oscar Wilde story The Happy Prince, himself providing the fruity and fluting recitative that linked the songs.

In early 1970 Rawlins was the master of ceremonies at the pioneering ‘Pilgrimage For Pop’ at Ourimbah on the NSW central coast. In his surprisingly practical Festivals in Australia: An intimate history he recalled that Ourimbah remains ‘the most beautiful, the most ideal’ site for a festival ‘and the only one with a real abundance of lavatories’ (it had army-style latrines for 400). At Ourimbah an audience of 3000 ‘mainly hard-core psychedelics’ in oriental and middle eastern outfits were overseen by armed police with guns who ‘stood around eating ice-creams’. There were two arrests for drunkenness and one for indecent language; 114 unroadworthy vehicles were identified. The following summer Rawlins hosted the Wallacia and Myponga festivals, declaring at the latter ‘The age of historic high cultures is at an end. [It is] an age when rhythm brings a new and real spiritual uplift to the young. The kids are responding to vibrations within themselves, rather than to conventional standards imposed from without.’ The first genuinely profitable rock festival was the first Sunbury in 1972, at which he was co-compere.

In 1976 Rawlins turned up at the heaving Down To Earth Festival, convened by Jim Cairns and Junie Morosi at the Cotter Reserve in Canberra. As documented in photographs by Kapil Arn of the Dharma Press, most people there got naked at some stage. ‘Inchoate, ecstatic dancing was taking place … More and more people stripping off all vestiges of clothes and plunging in … Hundreds of people were standing in thigh-high water, swaying, humming OM … There were so many, at least a thousand, we had to form circles within circles. We had to show tangibly that we really all were one … And in a minute we were all threshing, splashing like children, laughing and crying. And when this celibate orgasm was over, many of us relinked our arms and began again singing “Give Peace a Chance”. We continued until sunset.’ In the sunset of his own life, the late 1980s and 1990s, Rawlins was involved with the Canberra-based publication Blast; during this period he read his poetry in the film John Olsen: journey through ‘you beaut’ country. In 1999 his These days, those days: A Saga of Today was issued in an edition of five copies, each signed by the author. Two years later, he died. A startling life-sized sculpture of him by Peter Corlett called The laughing poet sits atop a column in Brunswick Street, Fitzroy, where he used to sell audiotapes of himself reciting Shakespeare’s sonnets to passers-by.

The portrait of Rawlins was Campbell’s first Archibald entry, and with it he became the youngest artist ever to have work hung in the competition. Other Archibald portrait subjects that year included Jim Cairns and ABC newsreader James Dibble. Campbell’s next portrait subject was the ABC’s ‘it girl’, Caroline Jones AO (b. 1938).

The portrait of Jones, like that of Rawlins and the later portrait of Fay Bottrell, incorporates elements of Campbell’s customary practice in abstract watercolour works. He wrote that the creation of these works ‘is an attempt to share my emotional and intuitive awareness of the world I am experiencing. Controlling colour within a contrived format forces me into an exquisite seeing. I work with music and have a love of the sea. The colour synthesis in my work, I hope, embodies the spirit of both, portraying more than is held within the frame.’ In August 1979, in a daring mash-up of fashion and art for the people, 22 Myer windows fronting two Sydney streets were filled with mannequins posed amongst his watercolour paintings.

Even as he prepared works for the Myer frontage, the portrait of Jones was an immersive project for the young artist. He spent hours in the ABC studios during the taping of her programs, studying and sketching her expressions, personality and mannerisms. In his view, it didn’t suggest exhaustion; discussing the work with a Central Coast journalist, he preferred to describe Caroline Jones’s arresting expression as ‘tentative’. Its composition still startling, Campbell’s portrait shows Jones’s head much larger than life size, her famous eyes a soft dark blue, her hair rendered in shades of olive and teal, her lower body dissolving into abstract lines dribbled over darkness.

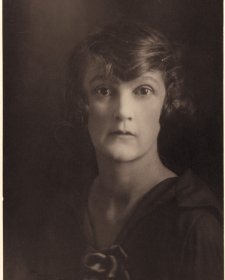

Campbell had known his last subject, textile artist Fay Bottrell, for some years before he painted her. Born in 1927, Bottrell came to Sydney from the Riverina as a sixteen-year old, and worked for a herbalist. After war service with the AAMWS she studied art and became a textile designer and colour controller in print and dye works. Living in a commune at Barrenjoey Lighthouse, she mixed with the Push and in due course went to India to study cottage industry. For a while she lived in North Queensland, where she and her husband, cartoonist John Endean, made their own bricks to build a studio. When Mary White set up her School of Art at New South Head Road, Edgecliff in 1961 Bottrell was one of the prominent artists and designers (including Brian Dunlop, Robert Klippel and John Olsen) whom she recruited as teachers, mentors and artists-inresidence.

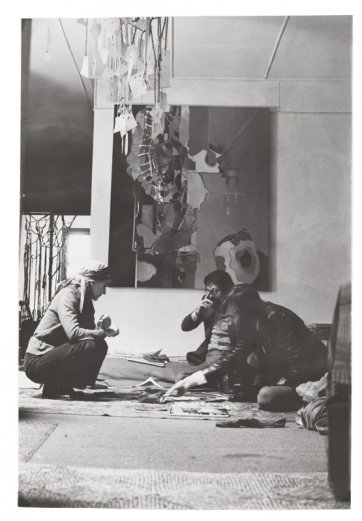

The 1970s saw a revival in the fibre arts with a new emphasis on off-loom, sculptural weaving (popularly exemplified by macramé). Bottrell’s work from this period is represented in the Craft Australia National Historic Collection. Having collaborated with Wesley Stacey on the book The Artist Craftsman in Australia: Aspects of Sensibility in 1972, she created the happening Fabrication for the opening of the Festival Theatre Gallery in Adelaide in 1973, returning seven years later to install a second happening, Glad to Be. She was the design consultant for the first Festival of Sydney, and taught at the Alexander Mackie College in the mid-1970s. Having made a mammoth work for the International Year of the Child for the Arts Council of New South Wales, in 1979-1980 she made two large woollen tapestries for the new State Parliament House, and was commissioned by Premier Neville Wran to make a patchwork of harbour flags.

As Christmas approached in 1979 the Women’s Weekly ran an article about Fay Bottrell’s home and studio in Matcham (where she still lives, surrounded by millionaires’ retreats). Titled ‘The House that Junk Built’, it was accompanied by pictures of Bottrell surrounded by a litter of fabric scraps and squares, hanks of yarn hanging around her like jungle lianas. ‘Throughout the house there’s a lot of evidence for Fay’s preference for recycling’, wrote a bemused Babette Hayes. ‘The floors, for instance, were originally covered with lino in a demanding pattern, so she changed it by simply turning it over ... The walls are brown, as are the ceilings, all the woodwork, and the non-matching pieces of furniture, because she managed to get brown paint cheaply at a disposal store sale … A rich mural is made of coloured paper strips, cut from old magazines in varying widths and lengths, and then stuck to the wall … In the bathroom, the walls are covered with foil paper … a vase holds artificial flowers made from recycled coloured pantyhose.’ While living in this sanctuary with Endean and their children, Bottrell was commissioned to work on a mural for Consolidated Press in the Sydney CBD. Campbell had made an impression on her as a student – she had recently recommended him for a residence at the Tasmanian School of Art – and his studio was very close to the Consolidated Press offices in Park Street, so she revived their acquaintance and arranged to stay there, returning home on weekends. Campbell capitalised on her proximity to paint her portrait. Now, she recalls feeling awkward crouching in the position he wanted; the dynamic effectiveness of the finished work notwithstanding, she says that she only ‘obliged to be gracious’. In exchange for her accommodation, she bought the only oil painting he had in his studio.

While living and painting in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales, David Campbell was killed as he rode his motorbike back to Sydney to work. At his funeral, a tapestry of flowers by Bottrell was spread over his grave.