The history of French fascination with Australia and the Pacific is populated by remarkable individuals and incidents. Consider these examples: The navigator Yves-Joseph de Kerguelen de Trémarec, sent by Louis XV in 1771 on a secret mission to locate the great south land but later imprisoned for pretending he had found it.

Jeanne Baret who, disguised as a man, accompanied her lover, the naturalist Philibert Commerçon, on Louis-Antoine de Bougainville’s 1766–69 circumnavigation of the globe. Jean-Francois de Galaup, the Comte de La Perouse, whose expedition sailed, disconcertingly, into Botany Bay in January 1788, a mere four days after the arrival of the fleet sent to bag the east coast of Australia for Britain. Or Louis-Claude de Saulces de Freycinet, the explorer who embarked on his second southern voyage in 1817 with his pretty wife, Rose, stashed in his cabin.

Yet these and numerous other vignettes, some vivid, some sordid, often remain obscured. So versed in the recitation of names like Cook, Banks, Bass and Flinders, Australian memory seems to stumble somewhat at the recollection of a Marion Dufresne, Saint Aloüarn, d’Entrecasteaux, or Baudin, remaining unaware of the equivalence of French contributions to the knowing and seeing of Australia’s shape, nature and people. Britain’s territorial ownership of the continent is common knowledge. But France’s intellectual and imaginative possession of it is less known, despite a century’s worth of French antipodean discovery that started with Bougainville in 1766 and concluded in 1840 with Jules Sébastien César Dumont d’Urville claiming a slice of Antarctica for his homeland. Financed by the state, these expeditions were coloured by politics and imperialism. The voyage of Bougainville, for example, was undertaken in an atmosphere of national pride deflated by French territorial losses in America incurred in the Seven Years War. That of Kerguelen was conducted partly in riposte to the British - an attempt to disprove the conclusion reached by the feted Captain Cook that an inhabitable continent was not to be found in the southernmost latitudes of the Pacific. Kerguelen failed, mistaking Île Kerguelen in the Southern Ocean for the mythical land while his deputy, Louis François de Saint Aloüarn, took possession of the western half of Australia for France. But French exploration was equally defined by the noble and supposedly neutral objectives of science. Men like La Perouse, Freycinet and Nicolas Baudin had their eyes on prizes beyond the déclassé acquisition of territory, their voyages instead motivated by a desire to capture – through cartography, botany, zoology and portraiture – the marvellous natural and ethnographic riches of terres australes.

It was Cook’s achievements in the Pacific that inspired King Louis XVI to sponsor the first of these expeditions displaying Enlightenment France’s commitment to knowledge and discovery. Jean-Francois de Galaup, Comte de La Perouse was appointed to its command. La Perouse left France in August 1785, his complement of 225 containing men that British officer David Collins later termed ‘people of the first talents for navigation, astronomy, natural history and every other science.’ La Perouse’s ships, L’Astrolabe and La Boussole, were correspondingly equipped for the study of climates, peoples, plants and animals to be encountered in the course of surveying the north and south Pacific oceans. While in Kamchatka in September 1787, La Perouse received word that the English were on their way to the east coast of Australia and, under instruction to observe the activities of other European powers in the region, he decided to investigate. The presence of La Perouse’s two ships off the Sydney coast, not surprisingly, was among the first events noted in the measured accounts penned by the chaps who had arrived with the First Fleet only days earlier. Phillip Gidley King wrote of January 24th 1788 that ‘in the morning two strange ships were discovered to the southward of Cape Solander & we soon discovered that they were French … from which we conclude them to be La Boussole & L’Astrolabe under the orders of Monsieur de La Perouse on discoveries.’ The journal kept by surgeon George Worgan hints at some initial unease, the French officers, he noted, being ‘rather reserved in making us acquainted with the route they had taken, and the discoveries they had made since they arrived in these seas.’ The relationship then became less guarded, both sides recording friendly visits during the six weeks of La Perouse’s stay, their ‘civilities’ discomfited only by the matter of some convicts who nicked off to Botany Bay and ‘applied earnestly to be taken on board’ the French ships. These exchanges with the British were the expedition’s last contact with Europeans: La Perouse sailed from Botany Bay in March 1788 and disappeared.

Before departing Sydney, La Perouse had entrusted to Governor Phillip documents outlining a proposed itinerary for the remainder of the voyage. These plans, taken to Europe in July 1788 along with Phillip’s first official dispatches home, gave a template to the expedition, led by Antoine Raymond Joseph Bruny d’Entrecasteaux, to find La Perouse two years after his anticipated date for return had elapsed. D’Entrecasteaux sailed from Brest in September 1791 with two ships, the Recherche (Search) and Espérance (Hope), his instructions being not only to find evidence of the vanished expedition, but also to make further examination of the west Australian and Tasmanian coasts, the Gulf of Carpentaria, and various other islands. Despite sailing close by to where La Perouse’s ships were eventually found to have been wrecked (near Vanikoro, north of Vanuatu), d’Entrecasteaux remained empty handed on the search and rescue score. But on that of expanding European acquaintanceship with Australia d’Entrecasteaux excelled. The shape of his voyage is traceable in the place names associated with it, such as Esperance in Western Australia; or Tasmania’s d’Entrecasteaux Channel, Bruny Island, Recherche Bay, and Huon River. Its intellectual spirit is preserved in the thousands of botanical and zoological specimens collected by the naturalist, Jacques Julien Houton de Labillardière. Labillardière’s collection survived being seized by the British when the expedition disbanded in 1793 in the wake of the French Revolution and was eventually, through the intervention of Joseph Banks, returned to France. Some of the specimens collected by Labillardière were later successfully cultivated at Malmaison, a chateau belonging to Napoleon Bonaparte’s lady, Josephine, who commissioned botanical artist Pierre Joseph Redouté to record them.

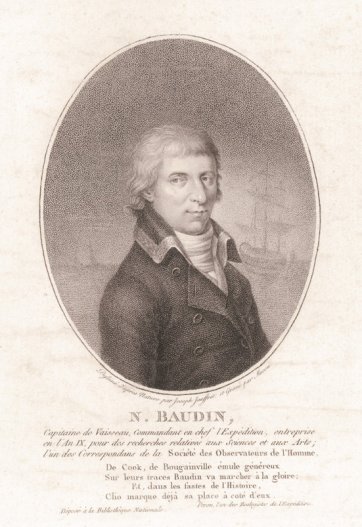

Josephine’s jardin botanique and menagerie at Malmaison shared also in the spoils of the voyage initiated, in the midst of war, by navigator Nicolas Baudin and aimed at the demonstration of French scientific and geographic prowess. Napoleon, an unsuccessful applicant for La Perouse’s expedition, endorsed the venture, consequently ensuring that Baudin’s vessels, Géographe and Naturaliste, were lavishly equipped and adapted to accommodate the complement of twenty-two savants and artists and the numerous specimens – animal and plant, live and otherwise – they would be capturing and collecting. Baudin departed France in October 1800, taking six months to get to Mauritius where shipboard conditions and personality clashes resulted in fifty men deserting the expedition. With none of the official artists left, Baudin assigned the task of creating the expedition’s visual record to two draughtsmen he had enlisted, in the guise of gunner’s mates, as illustrators for his personal logbook: Charles Alexandre Lesueur and Nicolas Martin Petit. In company with François Péron – the assistant zoologist who, on the deaths of his superiors, became Baudin’s primary naturalist – Lesueur collected countless specimens of land and marine life, many later documented by his meticulous drawings and watercolours. Their labours are notable as much for their success as for their scale: the many thousands of natural history specimens unloaded in France included seventy-two Australian animals and birds kept alive during the voyage, Baudin tells us, with a diet involving rice, wine and sugar.

Yet Baudin’s voyage is perhaps more notable for its transactions with people, particularly its chance meeting, in Encounter Bay, South Australia, in early April 1802, with the rival expedition led by Matthew Flinders. Flinders, like Baudin, was engaged in the closing of cartographic gaps, his famed circumnavigation of Australia in the Investigator prompted in part by British unease that Baudin’s stated ‘scientific’ motivations concealed duplicitous imperial designs on what the French called ‘Terre Napoleon’. Though of less dramatic impact, Baudin’s meetings with Indigenous people were of richer human magnitude and resulted in portraits considered among the most important created by European artists at the time of first contact.

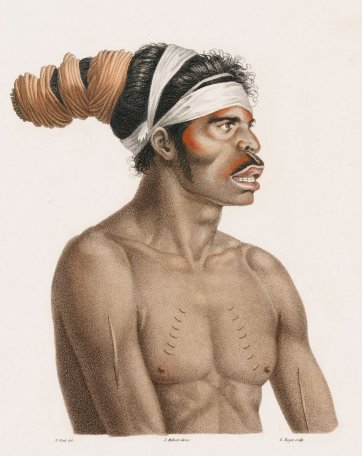

With Lesueur mainly focussed on the recording of landscape and species, the preservation of human encounters and curiosities fell to Petit, who made drawings of Indigenous people in Tasmania and New South Wales. His Tasmanian portraits are considered precious as depictions made before European settlement had decimated Indigenous ways of life, and are evidence of the expedition’s particular attention to the study of native peoples. Petit also made a series of portraits during a five-month period of refit and recuperation in Sydney in 1802. Such portraits as those of the Eora men Cou-rou-bari-gal and Y-erran-gou-la-ga, though documenting people who Baudin regarded as having ‘lost their primitive customs’, are just as plentiful in their detail of skin colour, cicatrices, body decoration and adornments, their noble, sculpted forms and contours betraying Petit’s training in the studio of Jacques-Louis David. Though incomplete at the time of his death, aged twenty-eight, in 1804, Petit’s record of the journey was drawn on to illustrate the official account of the Baudin expedition – co-authored by Freycinet and Peron following Baudin’s death from tuberculosis on the return voyage to France.

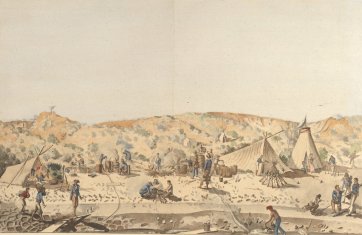

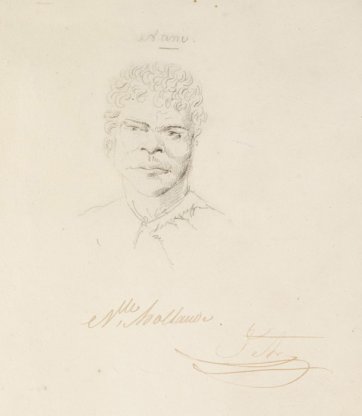

This tradition of accurate and sensitive, if romanticised, depictions of Indigenous people continued in the work of the artists assigned to the voyage conducted between 1817 and 1820 by Freycinet, Baudin’s cartographer and surveyor. Before foundering on the Falkland Islands in February 1820, Freycinet’s expedition – with which France sought to reassert itself as a leader in matters of discovery and science – accomplished almost three years of charting and observations, among which were those of the cultures and customs of Indigenous peoples in Australia and the Pacific and snared in written and visual accounts of Freycinet’s enterprise. Rose de Freycinet who – in brash contravention of a royal order forbidding women from French naval vessels – was smuggled aboard her husband’s ship L’Uranie before it embarked from Toulon, left a record of the expedition’s progress in a journal kept throughout the voyage and eventually published in the 1920s. The notes Rose made while at Shark Bay, Western Australia, in September 1818, for example, recorded the tension of the expedition’s meeting with ‘a band of natives, all naked, armed with assegais and spears’; and a subsequent incident wherein the Aboriginal people hesitatingly ‘exchanged their weapons for tin, glass necklaces and so on.’ Though erased from the official, published narrative of the expedition, Rose is present in the images created as a result of these encounters, such as the drawing by Alphonse Pellion of the French camp at ‘Baie des Chiens-marins’. Like Rose, expedition draughtsman Jacques Etienne Victoire Arago logged the Freycinet journey in letters, published in 1822 as a book titled Promenade Autour du Monde, as well as in a collection of drawings and portraits that illustrated this and Freycinet’s ten-volume history of the voyage. Among his better-known Australian images is Arago’s tableau of an officer gifting trinkets to the Aboriginal people at Shark Bay, in which Arago depicted himself playing castanets, presumably to ease the tension. In addition to the many images he made of Indigenous people in places such as Timor, Hawaii and Guam are pencil portraits of five Sydney men, drawn during a six-week stay there in late 1819. Arago’s written accounts of Eora people as ‘poor creatures’ with‘ feeble constitutions’ and habits he considered ‘barbarous’ and devoid of gallantry, are belied by his idealised, classical portraits of these sitters. Like Petit, Arago in his portraits of these Sydney people combined the purely observational and documentary with artistic convention and a complex awareness of the effects of European contact.

Although not always as readily recalled as those by their British counterparts, the additions made by French travellers and thinkers to knowledge of Australia and its people are just as abundant. They can be witnessed in the many names given by French explorers and mapmakers to land and water, but reside rather more expressively in the rich material evidence of France’s appetite for knowledge of the antipodes – the memoirs, specimens, maps, topographical views and botanical drawings held in museum collections here and overseas. They are evident also in the portraits of and by those intrinsic to their country’s contract to understand and visualise an unknown south land: those involved in creating the immense body of geographic, ethnographic and scientific knowledge of an Australia with French blood flowing in its veins.