Eight years ago, the writers Dorothy Porter and Andrea Goldsmith were two of those shortlisted for the Miles Franklin Award. Goldsmith’s book, The Prosperous Thief, was dedicated to Porter. Porter’s book, Wild Surmise, was dedicated to Goldsmith.

It is often pointed out that in the history of the award, it was, and is, the only instance of such a coincidence. It wasn’t, however, much of a coincidence. The two women had been together for more than a decade; and through that time Dorothy Porter had poured her passionate love for Andrea Goldsmith into poems.

Porter, born in 1954, grew up in Sydney, spending a lot of time in the Blue Mountains. In the year she turned twenty-one her first book of poetry was published: Little Hoodlum (1975), its cover featuring an uncompromising photograph of the author in mannish jeans and beanie. Having graduated from the University of Sydney and qualified in education, she taught creative writing while writing Bison (1979), The Night Parrot (1984) and Driving too Fast (1989). In the early 1990s she wrote two novels for young adults. Akhenaten, the first of the novels in poetry for which she was to become renowned, was published in 1992. The book remained a favourite; the iconoclastic pharaoh Akhenaten, husband of Nefertiti, was, she said, closer to her than any of her other characters.

It was in 1992 that Dorothy Porter met Andrea Goldsmith. Four years older than Porter, with astounding blue eyes, Goldsmith had trained as a speech pathologist and was a pioneer in the development of communication aids for people unable to speak. Her first novel, Gracious Living, was published in 1989 and she had followed it up with Modern Interiors. On the first day of a week-long trip on the Victorian Women’s Writers’Train in autumn 1992, Goldsmith was affronted by Porter, whom she found noisy and intrusive. That night, however, when Porter read from Akhenaten, Goldsmith was transfixed by a performance the like of which she had never seen. Before an audience the woman was ‘utterly seductive’; she was ‘literally breathtaking’. Later, Porter was to inscribe one of Goldsmith’s copies of Akhenaten ‘the book that made you look at me twice’. In 1993, Porter moved to Melbourne to live with Goldsmith, who was her partner for the rest of her life.

Goldsmith is an essayist and reviewer as well as a writer of fiction; she is passionate about music and food. Early in their relationship, she was taken aback to see Porter ‘shovelling’ in meals that she had planned and finessed. Porter was oblivious of decor, too. Words were their common ground. In a memoir of their life together, which progresses like a musical piece through three distinctively beautiful movements, Goldsmith recalls that the literary lovers often gossiped to each other, and laughed when they imagined how shocked people would be by the banality of their talk at home, where they were Dot and Andy to each other.

Over the years in which their lives entwined, Porter wrote of Goldsmith from many perspectives. In ‘Kaua’i’, a poem ‘for Andy’, she recalls drinking tropical cocktails as the rain fell heavily around their shelter: ‘Like a tent of humid hair’: this is paradise. / slightly pissed. / watching the sea and the mountain / moving in and / out / through the mist / like our own strange souls.’ In ‘Why I Love your Body’, Porter is characteristically direct about one of the great consolations of life partnership – to be granted an exemption from having only one’s own body, ageing, remembering, dwindling, forgetting, to think about: ‘I put your body / between me / and the history of horrors / I put your body / between me / and the terrifying future / of my body.’ There is also sex, spent from which: ‘My mind goes almost quiet / faintly squeaking to itself / like a fruit bat dozing / upside down.’ And the joy of routine, as Andy, the earlier riser, comes to greet Dot and their cat on the bed: ‘how lucky I am / to hear you, darling, / coming up the stairs / to smell the coffee / floating ahead of you / like my favourite incense.’

In her preface to a posthumous volume of Porter’s love poems, Goldsmith wrote that from the first, and in all the forms of writing in which she was to engage, it was love that was Dorothy’s irresistible topic. ‘It was love’s dark and tricky aspects that most attracted her as a writer... She had a particular fascination for the unpredictable dangers that threaten when one gives into an all-consuming passion', she writes.

All-consuming passion saturates The Monkey's Mask (1994), which won the Age Book of the Year for Poetry, the National Book Council Award for Poetry and the Braille Book of the Year. The Monkey’s Mask staked out the demotic verse novel as a territory all Porter’s own (in a strong review in 1997, the Independent warned readers that they would have to restrain themselves from reading it at a sitting). Widely translated and published overseas, it was adapted for stage and radio and made into a film starring Kelly McGillis and Susie Porter. Her subsequent work in the same genre, What a Piece of Work (1999) was shortlisted for the Miles Franklin and its successor, Wild Surmise (2002) snatched up South Australian Premier’s awards for Literature and for Poetry in a single swoop.

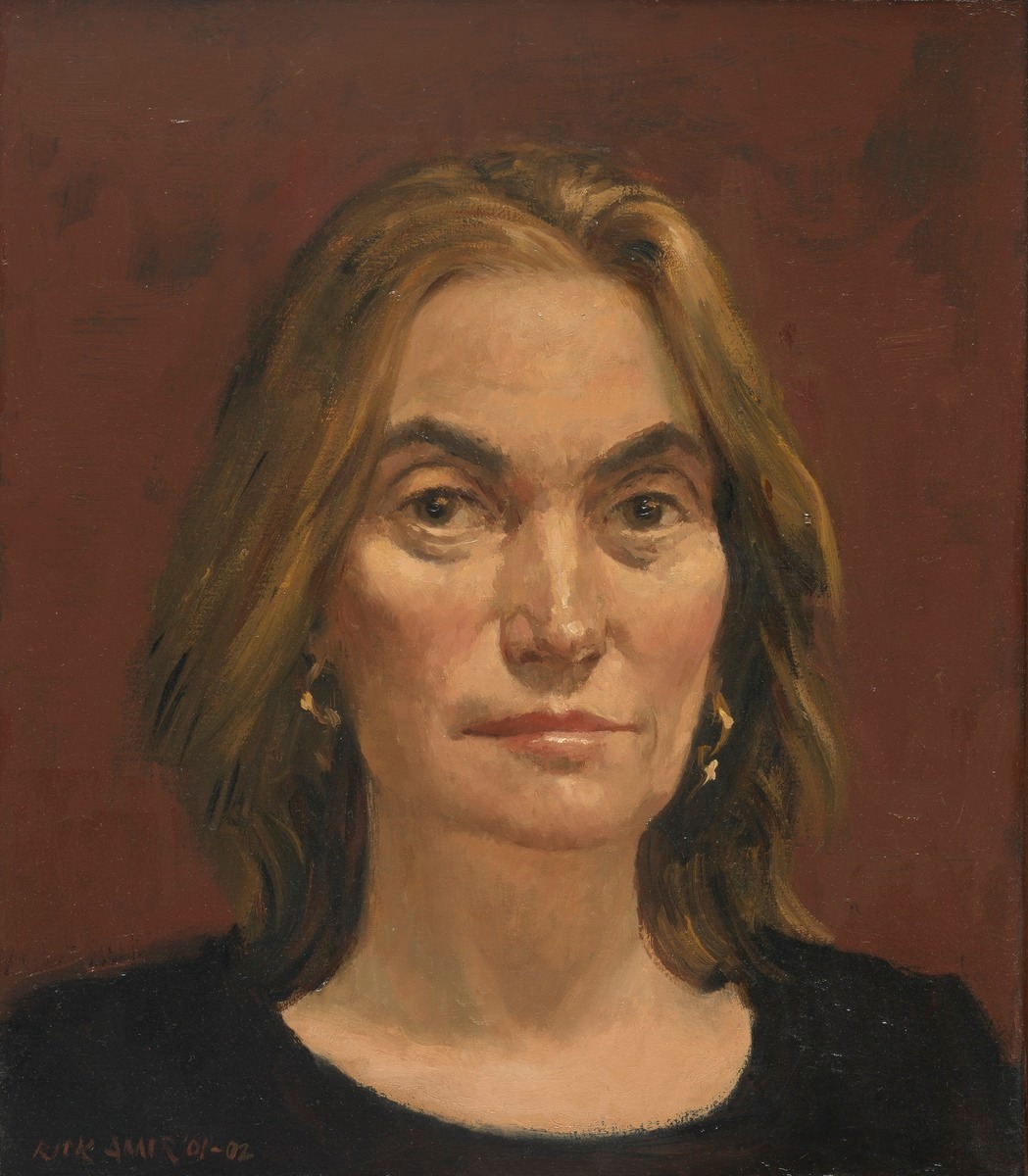

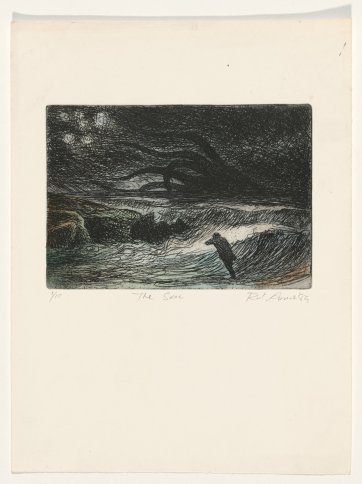

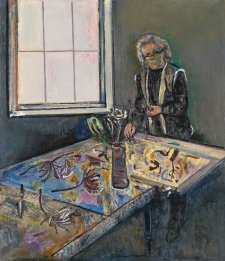

Goldsmith and Porter lived amongst art, and the work of Rick Amor was not unfamiliar to Andrea, at least, for her mother had the artist’s woodcut of Manning Clark. Amor, unacquainted with Porter, first saw her on television. Intrigued that she didn’t smile, he made a drawing of her as he sat and watched her talk; his interest in her increased when he read The Monkey’s Mask. Soon after, she was signing books at Readings, the pair was introduced and he asked if she would like to sit for him. As Goldsmith puts it, ‘he got hold of her work and then he got hold of her face’. Henceforth she and Porter lived in consciousness of, and amongst, Rick’s work. He gave Dorothy his print,The sea, in tribute to ‘Giant Squid’ in which the poet evokes a dream of a tranquil entanglement at the bottom of a soft black sea: ‘our strange / mutually enraptured / breathing / in perfect unison / as we nibbled on / each other’s preciously / alien faces.’

Hardly anyone saw Porter in repose, even Goldsmith, who remembers that even when she was reading, her expression flickered. Michael Brennan wrote, after she died, about ‘how Dot was in the day-to-day’, in conversation, correspondence, and in friendship: ‘Shining. Loving. Illuminating. There was an urgency to Dot, a tireless energy and passion for life as much for language, a bright and rational light that opened up the mundane and half-said, an optimism and creativity that made anything seem possible. Poetry as a popular art form? Poetry as commercially viable? Poetry as a career? In Australia!? … Dot just went ahead and did it, tenacious, openhearted and straight-talking all the way.’ Fittingly, the last piece she completed before her death from complications of breast cancer was the rumination ‘On Passion’ (2009).

Amor’s austere and formal painting, showing Porter as hardly anyone ever saw her, is a very small one. She and Andrea were pleased by the way the tininess of the painting worked against the hardness of it; the fact that people had to come in close to the forbidding face. They talked about what they would do with it. Avid visitors to the National Portrait Gallery in London, they had been thrilled when the Portrait Gallery opened in Canberra, where Porter dared to hope that she might be represented one day. Two years after Dorothy’s death – a time when, she has written, she felt the world tugging at her to join in – Andrea felt that the time was right to let the portrait, too, take its place in the world outside their home.

Rick Amor once said ‘you don’t say to someone, “stay still a minute so I can see your soul”’. It was a typically commonsensical assertion from the painter, but he is nonetheless a man who has had occasion to contemplate his own mortality, and whose many sombre self portraits speak of unsparing self analysis. Porter, a spiritual person, romantic and pantheistically alive to otherworldliness in situations and things, did feel that Amor had rendered something more than her face in the portrait. Goldsmith resisted the work for a time, because it wasn’t the woman she knew; but Porter faced her own likeness with more objectivity as it hung in her study. The women agreed that the portraitist hadmade Dorothy look older than she was. It was some time before the painting came to seem, to Andrea Goldsmith, to show her true love as she might have looked, in the future that she lost.