In due course, Harding developed the nerve to approach Bell about a portrait, and they discussed the idea over morning tea with Rex Irwin, a friend in common. One appointed day Harding took his drawing materials down to the Wharf Theatre, where Bell was rehearsing Strindberg’s Dance of Death. Having arrived early, the artist was sitting reading the paper in his car, when he spied a moustachioed Bell emerge from the building. Harding was arrested by the intensity of his expression – even though Bell was walking a dog. For the sitting they went to a dance rehearsal room, but the moment they entered that ‘nowhere’ space Bell seemed uncomfortable under scrutiny and the session didn’t come to much. Later, in Bell’s office in the Rocks, the artist drew him as he dictated a letter. The resulting Portrait of John Bell was a finalist in the Archibald Prize of 2000. Harding found, however, that the actor wasn’t out of his system; having always had his performance of Lear in mind, he felt equipped, now, to embark on a portrait expressing Bell’s passion for Shakespeare.

As the works in the 2000 Archibald toured Australia, Harding, flat broke and living on a stipend from the Irwin gallery, began work on another painting of Bell: this time as King Lear, wearing the red double-breasted greatcoat from the Kosky production. The Archibald had reached Melbourne when Harding took a call from an arts administrator, who asked him if he was sitting down. As the works were being unloaded from a hot truck, the corner of another painting had gouged Portrait of John Bell. The damage was irreparable. However, what must have seemed like the worst possible news to the person who had to relay it came with a substantial silver lining. The insurance money was enough for him to secure the huge amount of paint he needed to finish the second portrait of Bell, as Lear.

Harding hasn’t often experienced the thrill of feeling that he’s carried a portrait off, but he felt buoyant about John Bell as King Lear. It was chosen for the 2001 Archibald exhibition without Bell’s ever having seen it; and it won. John Bell conferred his Archibald favours very graciously, making himself available to pose with his likeness, as sitters traditionally do. When the announcement was made, and the artist found himself too nervous to respond, he called on the thespian to speak in his stead. Bell, in his turn, made up a charming fiction of glancing down from the stage, and, seeing the artist sketching in the audience, taking pains to present his best profile whenever he could. Harding managed to stammer in his delight that as pleased as he was with the portrait’s rendering of Bell’s energy and power, and of his eyes, Bell’s was certainly ‘the best nose I’ve ever done’.

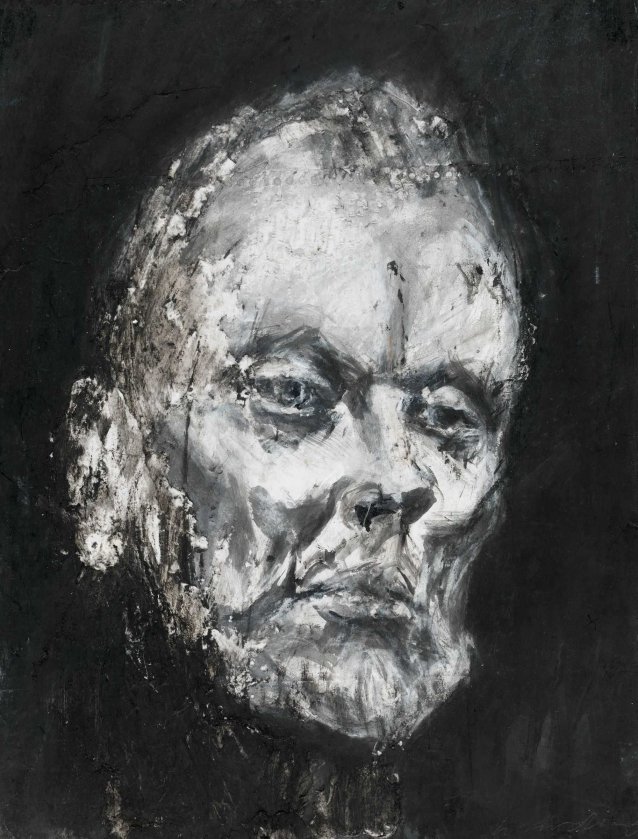

The ink, charcoal and conté portrait of Bell in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery appears to be a preparatory sketch for the finished painting; but in fact, the drawing formed alongside the portrait, rather than being created before it. It helped the artist find his way; but as indicated by the date of 1998-2001, it did so along the way.

John Bell as King Lear was tipped, by pundits, to win the Archibald from the outset. The only carping remark about Harding’s victory came from a critic who asked if the portrait breached the rules of the competition, as it ‘essentially’ portrayed a character, not a ‘“real” person’. Somehow, he had calculated that the portrait was 70% King Lear and 30% Bell – although he admitted that it was difficult to know where one left off, and the other began. Let’s call the National Portrait Gallery’s drawing, in which Bell is stripped of his regal trappings and his expression is a little softer, 70% John Bell and 30% Lear. Though Harding found Bell’s performance in the great play riveting, the intensity of the finished work originated in that unguarded moment outside the Wharf, when John Bell walked out to clear his head, but hadn’t yet disengaged from his art.