Inner Worlds: Portraits & Psychology which opens 6 May 2011 at the National Portrait Gallery explores key moments of intense connection between psychology and portraiture in Australian art and social history.

The exhibition includes portraits of leading figures associated with psychological research and psychoanalysis in Australia from World War I to the 1950s, as well as psychological aspects of portraiture explored by Albert Tucker, Sidney Nolan and Joy Hester in the 1940s and, from the 1980s onwards by Anne Ferran, Dale Frank, and Mike Parr.

During the development of Inner Worlds unexpected connections emerged between Andor Meszaros a Hungarian architect, sculptor and medallion-maker and the anthropologist and psychoanalyst Geza Roheim and his colleague, Clara Lazar Geroe, both of whom were protégées of one of Sigmund Freud’s closest associates, the founder of the Budapest School of Psychoanalysis, Sandor Ferenczi. Theirs is a familiar theme of a shared fate; of political turmoil following the collapse of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire at the end of the World War I and eventual escape from virulent anti-Semitism as émigrés to the new worlds of Australia and America at the outbreak of World War II. Andor Meszaros and Clara Lazar Geroe arrived in Melbourne within a year of each other in 1939 and 1940 respectively. Geza Roheim would leave Hungary for the United States in 1938. Prior to their forced emigration, all were based in Budapest.

Following the political disruption in Hungary at the end of the World War I, Andor Meszaros trained as an architectural engineer in Vienna and then studied sculpture at the Academie Julien in Paris. Meszaros learned to carve under the guidance of émigré Hungarian sculptor Josef Csaky, one of the original Cubist sculptors, who lived next to Meszaros’s studio. Through Csaky he was introduced to Picasso.

In 1924, Meszaros returned to Vienna in order to complete his architectural studies. Having secured his diploma, he then moved home to Budapest. There from 1928 until his departure in 1939, he worked as an independent architect and architectural engineer and apprenticed himself to master sculptor Ede (Eduard) Telcs, who trained him in the European tradition of medallion making. Meszaros was also a keen competitive fencer; a sport that Hungarian nationals excelled in and, by a twist of fate, fencing would lead him and his family to Australia.

Geza Roheim was born into a wealthy Budapest merchant family in 1891. Through the influence of his grandfather he developed an interest in folklore and when he was at high school his father opened an account for him at one of Budapest’s oldest bookshops, giving him access to works on mythology and ethnography. By 1910, Roheim was a regular patron at Café Bristol, a gathering place for various Hungarian progressive groups and radical intellectuals including many young men who would make their mark on the twentieth century in philosophy, the arts, and the natural and social sciences.

Roheim was introduced to psychoanalytic theories through Freud’s treatises The Interpretation of Dreams and Totem and Taboo while at the universities of Leipzig and Berlin. He completed his PhD in geography at the University of Budapest, as there was no anthropology department at that time in a Hungarian university. By 1914 he was employed in the Ethnological Department at the Hungarian National Museum and worked there until his appointment in 1919 to the first chair of anthropology at the University of Budapest, a position he held until his emigration from Hungary to the United States in 1938. In 1915 he commenced his training as an analyst under the direction of Sandor Ferenzci and Vilma Kovacs at the Budapest School of Psychoanalysis and began to develop the discipline of psychoanalytic anthropology.

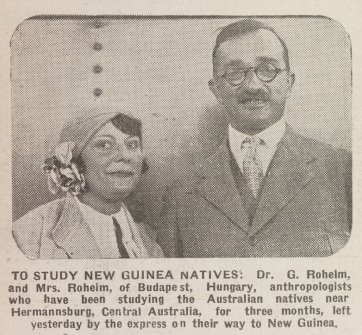

Drawing on the fieldwork of Australian anthropologists and ethnographers as well as Freud’s theoretical works, Roheim produced an academic paper entitled ‘Australian Totemism’, which was awarded the Freud Prize in 1921 for applied psychoanalysis. Recognising the need for empirical fieldwork, in the preface to his book of the same title he stated that ‘working in Budapest after the Great War upon a book dealing with Australian Ethnology is no easy matter’. Freud, Ferenczi and Kovacs approached one of Freud’s patients and benefactors, Marie Bonaparte, Princess of Greece, to fund Roheim’s proposed fieldtrip to Somaliland, Australia and the United States. Between 1929 and 1930, Roheim with his wife, Ilonka, as his assistant travelled to Hermannsburg Mission and Tempe Downs Station to interview members of the Arrernte, Pintubi and Pitjantjara tribes and to Normanby Island off the tip of New Guinea.

Roheim used psychoanalytic dream analysis to interpret Aboriginal myth, song cycles and ritual as well as children’s play. His initial report published in 1932 in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis was entitled ‘Psycho-analysis of Primitive Cultural Types’. This fieldwork continued to inform several major publications throughout the remainder of his career. He returned to Budapest in 1931 and continued to practice as a psychoanalyst with Ferenczi and his group and as an academic anthropologist at the university, until increasing hostility to Jewish professionals and the new ‘science’ of psychoanalysis, forced him emigrate.

By early 1938, American and British members of the International Psychoanalytic Association were increasingly anxious about the fate of their German and Eastern European colleagues. President of the association, Dr Ernest Jones, had already been contacted by Dr Paul Dane in Melbourne on behalf of a number of concerned fellow Australian professionals about the possibility of getting visas for European training analysts to come to Australia. The annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany in March 1938 increased the anxiety and pressure to find safe havens. By the time of the international psychoanalytic congress held in Paris in August 1938, Jones had successfully managed to convince Freud and his family to emigrate to England and was encouraging other members to consider New Zealand and Australia as suitable countries to emigrate to. However many of the Hungarian analysts present at the congress were still not fully aware of the imminent danger they were in. It would be the last time many of them would meet.

The names of six psychoanalysts were presented to the Australian government. In the end, two visas were offered and only one was accepted: Clara Lazar Geroe and her family. Geroe would become the first training analyst in Australia with the first psychoanalytic institute established in Melbourne.

Following the Anschluss and the Hungarian government’s increasing restrictions upon Jewish professionals’ ability to practice, Andor Meszaros sought advice from a friend at the of the University of Budapest who suggested he approach the British High Commission. The High Commission recommended Meszaros and his family emigrate to Australia. The enigma of Australia, and his decision to pursue the High Commission’s offer, was in part assuaged by a chance meeting in one of Budapest’s many competitive fencing clubs with Professor of Anthropology and psychoanalyst, Dr Geza Roheim, who lent him one of his books about Australian aboriginal myth and ritual and also spoke of his fieldwork experience in Central Australia nine years earlier. An interesting preparation for Meszaros’ migration! Roheim was a keen fencing champion and in competitions, was a regular partner of the Hungarian Olympic Fencing Team. It would appear that Meszaros’s milieu was the professional and academic elite of Budapest.

By April 1939, Andor Meszaros left for London and embarked by ship for Australia arriving in Melbourne in June. His wife Elizabeth and son Daniel would travel later once he was settled. Meszaros made the acquaintance of the brother of Melbourne tonal artist Max Meldrum, to whom he was then introduced. Meldrum sat for a medallion portrait and introduced Meszaros to one of his well-connected supporters, Elizabeth Agar, the wife of Wilfred Agar, Professor of Zoology at the University of Melbourne. Agar was also instrumental in providing introductions to Melbourne’s Anglican clergy, including Canon Farnham Maynard and Father James Cheong.

By 1941, Meszaros had cast sufficient medallions to mount an exhibition in Melbourne, which was opened by the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Melbourne. Although few sales resulted, following introductions from Professor Agar to academic colleagues in Sydney, Meszaros took this exhibition to Sydney in the hope of securing more work. It was a successful venture, resulting in several commissions for medallions, one being the foundation Professor of Sociology at the University of Sydney, Henry Tasman Lovell, one of the first academics in Australia to promote the study of psychology as a legitimate tertiary discipline.

Lovell had introduced Ernest Burgmann to psychology at university. Burgmann, later Bishop of Goulburn, regarded the study of psychology and psychoanalysis as valuable pastoral aids to healing troubled minds and a troubled society. Burgmann had also lobbied the Australian government to support Dr Paul Dane and the Refugee Council’s application to bring European training psychoanalysts to Australia which resulted in the emigration of Clara Lazar Geroe and her family.

Bishop Burgmann, Canon Maynard and Father Cheong were close associates. Bishop Burgmann would have been familiar with Meszaros’ huge bronze medallion of Father James Cheong cast in 1940 that hangs in St Peter’s Church, Eastern Hill Melbourne.