Joseph Banks was 25 when he sailed with James Cook on the Endeavour. At 35 he became President of the Royal Society. He was 36 when his support for the idea of Botany Bay as a site for a new English penal settlement made that settlement eventuate

Joseph Banks was born to Lincolnshire landowners in 1743 and grew up on his father’s estate, Revesby. At Eton, he became interested in botany, but at Oxford, he found that there was no one who could lecture him in the subject – so he paid for a lecturer to come from Cambridge. By 1764, at nineteen, Banks had come into his inheritance, and set up his bachelor lodgings in New Burlington Street. Two years later, he made the first of his dedicated botanizing excursions, to Newfoundland and Labrador, where James Cook had been serving in the Navy. Banks left Oxford without having gained his degree, but he was elected to the Royal Society nonetheless, in 1766.

At the age of twenty-five, he let the council of the Royal Society know that he wished to join the voyage of the Endeavour. Along with a substantial cash contribution to the costs of the voyage, the mere request was enough to gain him a berth on what was truly, for those who survived it, the ‘cruise of a lifetime’. Between August 1768 and July 1771, Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander collected hundreds of specimens of plants and animals of the South Seas, and Banks, at least, left much of his own seed abroad. Like Cook, he and Solander both became ill in Batavia; Banks, though terribly low himself, sat up all night with the critically ill Solander, and brought him through.

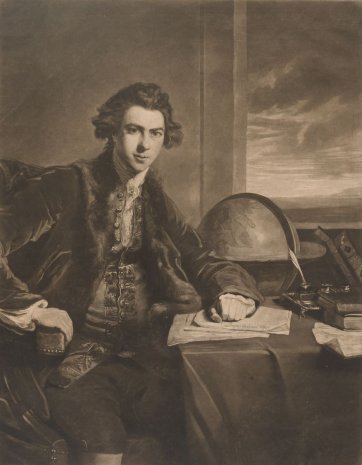

Banks’s status as one of the great stars of eighteenth century London scarcely fluctuated from the moment he came back to England in the summer of 1771 until his death in 1820. Soon after he returned, Benjamin West painted him attired in and surrounded by an assortment of splendid souvenirs from his Pacific voyage. Banks sat to Joshua Reynolds in the early months of 1772, as he was preparing to go on Cook’s next great expedition, on the Resolution, which was to be renovated to accommodate Banks’s extensive retinue and equipment. When Banks’s modifications, having rendered the ship unseaworthy, were dismantled, ‘Mr Banks declared his resolution not to go the Voyage, aledging that the Sloop was neither roomy nor convenient enough for his purpose,’ as Cook put it. Not long after the Resolution got under way, Cook wrote to Banks expressing his regret at the fiasco. Banks set off with Daniel Solander and a French chef to the Isle of Wight, Scotland and Iceland, retaining a lifelong interest in the latter.

At the time of the Resolution’s departure in June 1772, Banks had sulkily predicted ‘distress and disappointment’ as the chief outcomes of the expedition. While certainly distressing at times, not least for the sensitive and volatile German botanist, Johann Forster, the voyage was far from disappointing. Amongst other triumphs, Cook lost only one man out of 118 on an exceptionally arduous three-year journey, much of it in icy southern waters. Having acted like a goose at the outset of the voyage, Banks must have had mixed feelings about its success, and in particular about re-encountering Cook, covered in glory, in London. His dear Solander, however, was an effective intermediary. On 1 August 1775 he told Banks that Cook had just returned; ‘he said nothing could have added to the satisfaction he has had in making this tour but having had your company.’ Banks and Cook dined together at the Philosophers’ Club several times in 1776; around that time, Banks commissioned the well-known portrait of Cook by Nathaniel Dance, to hang in his Soho Square library.

Though he had had a better time than most abroad, and Reynolds’s 1772 portrait is inscribed cras ingens iterabimus aequor (‘tomorrow we’ll sail the vasty deep again’), by and large, after his short excursions with Solander, Banks stayed at home in London and Lincolnshire. In his biography of Banks, novelist Patrick O’Brian evokes the turning point:

There are many types of marine creatures, including the barnacle and the oyster, the very types of sedentary unstirring life, that have an active free-swimming youth; they when they are still quite young something comes over them – they find a convenient place, settle there, change shape, and never move again.

In his remaining years of bachelorhood, Banks lived with Solander; together, they picked over their huge store of specimens and curiosities, went on fishing trips with friends and ‘ladies of pleasure’, and entertained in the home of Banks’s mistress, Mrs Walls. Banks was cut to the heart when his learned and noble friend died in 1782. After marrying in 1779, he lived with his wife Dorothea Hugessen and his sister, Sarah Sophia. They were all to change shape together, in fact, expanding harmoniously over the years (this we know, as Banks kept a set of scales, enjoying recording the weights of his friends and family). O’Brian writes that the marriage ‘seems to have been thoroughly suitable and, unencumbered by children, thoroughly happy’.

Having served from 1773 as a ‘kind of superintendent’ of the Kew Gardens, in the serious development of which, in fact, he played a crucial role, Joseph Banks became President of the Royal Society in 1778. The same year came the first blockbuster temporary exhibition of the British Museum, of which Banks was a Trustee, and Solander Keeper of the Natural History Collections. It was a display of South Seas material brought back from Cook’s voyages. Having been established in 1753, the Museum only hit its stride with Banks as an advocate; henceforth, it developed alongside the Royal Society and reflected its areas of enquiry.

In April 1779, just a few weeks after Banks married, he gave evidence before a House of Commons committee on transportation, strongly recommending Botany Bay as a suitable place for a new penal settlement – much needed, with America in revolt. The historian John Gascoigne explains that the period between the end of the American war of independence in 1783 to the instalment of Henry Bathurst as secretary of state for the colonies in 1812 was one in which colonial issues were haphazardly directed. It was for this reason that Banks, being both President of the Royal Society and one of the few Europeans who had actually seen the east coast of Australia, became the government’s chief adviser on New South Wales. Incredibly, there was no department, agency or even person formally responsible for coordinating anything like a ‘strategic plan’ for the new colony. For its first two decades, from 1788 to about 1810, Banks held no official post but his role as effective head of Australian affairs was widely acknowledged. He was a patron of William Bligh, Matthew Flinders and others; and his tremendous interest in Australian natural history was sustained through correspondence and traffic in specimens with successive early governors of New South Wales. Hunter, in particular, shared his interest in natural history and exploration.

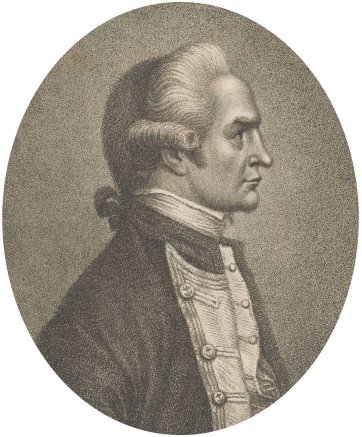

One of Banks’s first great causes, as President of the Royal Society, was the appropriate commemoration of Cook, news of whose death reached London in January 1780. After four years’ delay, Cook was commemorated in a medal, issued in gold, silver and bronze, bearing the inscription Iac Cook oceani investigator acerrrimus (‘James Cook, most intrepid investigator of the seas’). Never before had, and never since has, the Royal Society marked the death of one of its members in this way. The medal’s profile portrait of Cook was soon replicated in a print by Thomas Cook, surrounded by an engraved border of flaring coarse hair reminiscent of Hawaiian dog-tail fur.

Banks was convinced New South Wales, put on the world map by Cook, had the potential to be much more than a human dump and a drain on the Empire. ‘It is impossible to conceive that such a body of land, as large as all Europe ... situated in a most fruitful climate, should not produce some native raw material of importance to a manufacturing country as England is’, he wrote. He had sent a number of plants out to New South Wales with the First Fleet. He tried to send more in 1789 on the Guardian, which he’d had fitted out with a special ‘plant cabbin’; it was wrecked, but he succeeded with the similarly equipped Gorgon in 1791. That year, he was able to display some ‘very good ears of corn’ grown in New South Wales, and he soon sent more plants out, speculating that ‘in a climate similar to that of the South of France which Botany Bay probably is’ the vegetables he’d selected would be ‘highly useful’.

Lincolnshire, Banks’s ancestral seat, had been wool country since the fourteenth century, although the wool-based fortunes of Lincoln and Boston had waxed and waned. In the late eighteenth century there were renewed efforts to drain the fens of the area through a system of canals. As the sopping land dried off, pasture emerged. Banks was urged to become a member of the Lincolnshire Wool Committee in 1782, and from that point on, became keenly interested in sheep, particularly merinos (the volume The sheep and wool correspondence of Joseph Banks runs to nearly 700 pages). Through Banks’s negotiations with a French friend, the first batch of sheep scuttled from Provence to the coast and arrived at Dover on 3 January 1788. These beasts comprised the first lineup of His Majesty’s Spanish Flock, in which Banks was to become passionately involved. (In return, Banks sent his agent a kangaroo, France’s first, which arrived a couple of weeks before the fall of the Bastille in July 1789.) Some of the king’s beasts were obtained through negotiation with Spain, Portugal and France. A good proportion, however, were smuggled to England, including ‘Don’, the most-publicised individual ram of the Spanish flock, who was spirited ashore from the Betsy in 1790.

It is largely down to Banks’s personal enthusiasm for merinos that specimens of the breed were established in Australia within a couple of decades of English settlement. The first of their kind came to Australia from Cape Town in 1797; John Macarthur bought a few, and put them amongst his existing stock. On 9 July 1801 came a moment that decided the course of Australian history. Along with the returning governor, John Hunter, a box of fleeces from John Macarthur’s farm in New South Wales had come to London on the Buffalo. Banks examined them with his fellow expert, Henry Lacocke, and the pair found them promising. John Macarthur made personal representations to Banks in London in 1803, at which he emphasised that colonial flocks would free English woollen manufacturers from their risky dependence on Spanish fibre. Banks did not take to Macarthur personally; amongst other things, Macarthur had recently shot one of Banks’s friends in a duel. However, Macarthur was able to purchase seven rams and three ewes at the first public auction of merinos, supervised by Banks, near the Pagoda at Kew Gardens on 15 August 1804. Six of the animals survived to land at Sydney on 7 July 1805.

For a long and dispiriting time, it seemed that there would be no opportunity for the National Portrait Gallery to acquire a painted portrait of Banks, although many fine prints representing him in various phases of his life have been purchased and donated. For the inaugural hang of the Gallery in 2008, the National Portrait Gallery, London, lent Reynolds’s priceless painting from 1772. Thomas Phillips’s 1808 portrait of Banks as President of the Royal Society, which has been on loan to the Gallery from the Mitchell Library, Sydney, was originally commissioned by the Spanish astronomer and Fellow of the Royal Society, Jose Mendoza y Rios, a fellow of the Royal Society (who translated for Spanish shepherds Banks brought to England). He gave it to Banks, who liked it, and commissioned several copies, one of which still hangs in the Royal Society. The National Portrait Gallery, London, and the Linnaean Society both have versions of a portrait Thomas Phillips painted in 1810, with Banks seated, leaning slightly forward, his gaze direct and his right hand on his walking stick. The work acquired by the National Portrait Gallery is a copy of Thomas Phillips’s 1814 portrait, commissioned by the Corporation of Boston and now in the Boston Guildhall Museum in Lincolnshire. With a fen drainage plan in his left hand and papers at his elbow, Banks wears the uniform of the Lincolnshire Supplemental Militia, in which he had briefly been Lieutenant-Colonel, set off with the insignia of the Red Ribbon of the Order of the Bath, awarded to him by the King in 1795. Phillips became a fellow of the Royal Society himself in 1819, a year before Banks’s death and the end of his record reign as President. He painted his last, posthumous portrait of Banks in 1820, for the Royal Horticultural Society. That work, naturally, gestured at Banks’s botanical passions.

The list of events that transpired in Joseph Banks’s lifetime is scarcely credible. The time and place in which he lived gave him, like Cook, unrivalled opportunity to exercise his talents. Amidst the stellar figures propelling the Western world into modernity – and he knew a few of them – Banks was a steady, shining light. Despite his eminence, he retained an attractive quality of diffidence, consistent with his ‘very great capacity for friendship’ and his indifference to the age or social class of his friends. At the last, sure in the knowledge that he would die in his much-loved England, the man asked only to be buried, with no monument, ‘in the Church or Church yard of the Parish in which I shall happen to die.’ It happened to be in Heston, where his grave is unmarked, but a tablet, officiously installed in the mid-nineteenth century, records his illustrious presence in the nearby ground