The true motivations behind the British decision to start a colony in New South Wales have long been the subject of debate. Imperialism, strategy, the snaring of natural resources and the practical matter of relieving prisons swollen to bursting point were all reasons referred to in the instructions drafted for Arthur Phillip, the naval officer appointed the new colony’s first governor in 1786.

These instructions laid down what laws would apply to land, trade, exploration and convict management in the settlement that Phillip, with eleven ships and roughly one thousand people, established at Sydney Cove in January 1788. But residing amidst the pompous language and specific directions on matters as varied as livestock, women and wine are hints to some of the other motivations underlining this experiment. In the instruction that Phillip was ‘to endeavour by every possible means to open an Intercourse with the Natives and to conciliate their affections’, and the further stipulation that all of the intruders be ‘enjoined to live in amity and kindness with them’ resides evidence of a more substantial vision. An answer to crowded gaols and the suspect imperial intentions of other nations, the settlement at Sydney was also planned as an outpost of a ‘superior’ society, albeit one that countenanced the dispossession of Indigenous people at the same time as it courted their affections.

The complexities of these transactions are stored in portraits. Just as maps, journals, and other accounts of the colonial enterprise disclose the settlers’ attempts to make sense of their new world, it is possible to trace in portraits the templates for knowing and ‘civilising’ applied by the British to peoples and dominions, here and elsewhere. Their images of Indigenous people in particular document the curiosity characterising these encounters and, in the case of early Australian portraits, articulate just as powerfully the impact inevitably wrought on Aboriginal society as the British presence here hardened and expanded.

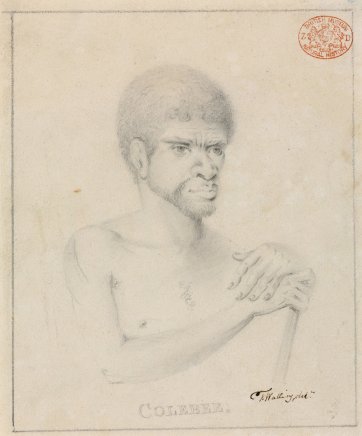

A diligent and honest officer, Arthur Phillip (1738–1814) has been noted for his efforts in fashioning friendships with the Aboriginal people, efforts which are cited as indicative of his obedience to orders as well as his tolerance and sensitivity. So observant was Phillip of the instruction to establish amicable relationships with Aboriginal people that, when the usual gifts and other peaceful attempts at fostering interaction failed, he resorted to kidnapping locals. The intention of this strategy was that, through gentle treatment and instruction in English, the captives would come to understand – and relate to their communities – the benefits of contact with the strangers. The plan was put into effect in December 1788 when a man named Arabanoo was lured into a boat at Manly Cove and removed to the British encampment, remaining there for five months until succumbing to smallpox in the outbreak of 1789. In November of that year – the settlement hungry, desperate and seemingly left for dead – the governor again ordered the abduction of Aboriginal men ‘for the purpose of knowing’, as marines officer Watkin Tench phrased it, ‘whether or not the country possessed any resources by which life might be prolonged’. Lieutenant William Bradley, one of the men involved in accomplishing this plan, described as ‘by far the most unpleasant service I ever was order'd to Execute’ his part in the capture of Colebee and Bennelong. Like Arabanoo, these men were baited with gifts of fish before being ‘seiz’d’ and taken to the governor’s house to be shaved, bathed, clothed and shackled.

It was in the years following such transactions and what is called the ‘coming in’ of Aboriginal people to the settlement that the most significant early Australian portraits were made. As with the mapping and naming of land and water, portraiture was part of the classification process. The images created by the colony’s first artists make it possible to see this ordering at work and make tangible the trust and inquisitiveness that characterised first contact. The artist and convicted forger Thomas Watling (1762–1814) arrived in New South Wales in 1792. One of few skilled draughtsmen in the colony at that time, Watling created a number of portraits of the Aboriginal people associated with the Sydney settlement, including Colebee and his wife, Daringha; and Nanbarry, a boy orphaned by smallpox and placed in the care of Watling’s employer, John White, the First Fleet’s principal surgeon. Given White’s bent for botanising – a trait typical of the colony’s educated gentlemen – Watling was put to work creating landscapes and images of botanical, animal and ethnographic specimens. Some of these drawings now form part of a collection of 500 works residing in London’s Natural History Museum. Known as the Watling Collection, it also includes examples of the work of the unidentified artist known as the Port Jackson Painter, who created a series of portraits and scenes of Aboriginal life in the period between 1790 and 1797. Like Watling, the Port Jackson Painter had ready access to Aboriginal subjects, his striking though naively rendered portraits recorded the faces of Colebee and Daringha, and also Ballooderry who lived for a time at Government House and of whom it was said that ‘among his countrymen we have no where seen a finer young man’.

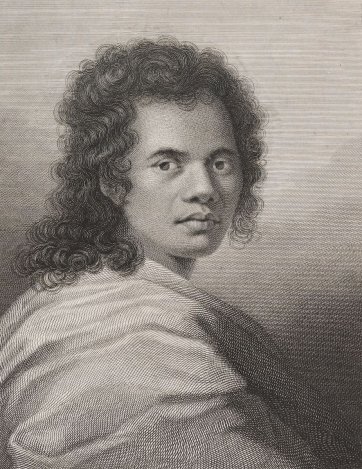

The Port Jackson Painter’s portrait of Bennelong (c.1764–1813) is a powerful and arresting likeness. It confirms Tench’s description of Bennelong as ‘of good stature, and stoutly made, with a bold intrepid countenance which bespoke defiance and revenge’, suggesting also the intelligence that enabled him to manipulate the governor’s favour to his own advantage. Unlike his fellow captive, who escaped soon after being taken, Bennelong remained with his gaolers for several months, exchanging names with Phillip to establish a form of kinship with him. Bennelong remained on good terms with the governor, even after the spearing of Phillip at Manly in September 1790 – an incident which some historians believe was a ritual punishment of Phillip for Bennelong’s imprisonment, along with other wrongs. Bennelong’s ‘powers of mind were certainly far above mediocrity’, Tench tells us. ‘He acquired knowledge, both of our manners and language, willingly communicated information; sang, danced, and capered; told us all the customs of his country, and all the details of his family economy.’ Bennelong adapted easily to British ways and became an astute intermediary between the two cultures despite their uneasy coexistence and his own fitful alliance with the intruders. Phillip, for his part, saw much value in the relationship and on his return to England in 1792 took Bennelong and his kinsman Yemmerrawanne with him in observance of the tradition of introducing Indigenous people into London society.

Images of Bennelong made in London present a contrast to examples of those of other Indigenous leaders accorded this curious distinction. Portraits of Mai (or Omai, c.1750–1778), a Tahitian man who travelled to England in 1774, evince London society’s fascination with him as warm, breathing evidence of the sensuous South Seas. In the course of his voyage on Tobias Furneaux’s Adventure (one of two ships engaged in James Cook’s second exploration of the Pacific), Mai was tutored in English language and manners and during his time in England was squired around town and to the court of George III by Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander – both depicted with Mai in William Parry’s triple portrait of 1775–76. Mai also sat for artists as distinguished as Sir Joshua Reynolds and Nathaniel Dance, whose splendid representations of his ‘tall and very well made’ white-robed frame were issued as engravings: evidence of his social success and of the appeal of the ‘noble savage’ to the worldly eighteenth-century imagination. That Mai went to England with an agenda that was perfectly clear to British reasoning – to secure allies and weapons with which to make war – might also explain the degree to which he was celebrated.

The Mohawk chief Thayendanegea, or Joseph Brant (1742–1807) likewise intrigued the British with his diplomacy and because, as diarist James Boswell saw it, he afforded ‘a very convincing proof of the tameness which education can produce upon the wildest race’. Brant had fought with the British during the Seven Years War and the American Revolution, was fluent in English and a convert to Christianity. He travelled to Britain twice, in 1775–76 and again a decade later, seeking to strengthen his alliance with the British while also airing grievances about the loss of Iroquois lands. On both occasions, he impressed with his ease of mobility between cultures. It follows that the many portraits of him blend symbols of both worlds. The stately 1776 portrait by George Romney, for example, displays Brant with a feather headdress and tomahawk but otherwise dressed in European clothes and adorned with the silver gorget that was a personal gift from the king.

Bennelong and Yemmerawanne too, according to an 1805 account, were ‘treated with that distinction and favour which the fashionable world lavishes on every novelty’. But they had nothing like the impact of visitors such as Mai and Brant and were subject to much less scrutiny. Some have argued that this can be explained by changing attitudes towards New World ambassadors that began to prevail after several decades of visits from delegations of ‘savages’, the first taking place in 1710 when members of the Iroquoian Confederacy known as the Four Indian Kings were presented to Queen Anne. Others have proposed that Bennelong was less readily celebrated for being from a people who existed, as Cook had said, ‘in the pure state of Nature’ and who thereby presented challenges to classification and the newcomers’ conceptions of value. Brant and Mai, on the other hand, were from cultures whose rituals and social structures, although curious, made them fathomable; and whose arts, agriculture and adornments were more easily admired.

The less elevated status of the Sydney men is confirmed by the scant material evidence of their visit. The Four Indian Kings had been honoured with paintings by John Verelst (said to be the earliest oil paintings of North American Indigenous people); and Mai and Brant likewise with portraits in the grand manner. But without the praise of the monarch or the connections of figures like Banks, Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne’s stay in London was recorded only in the merest of likenesses: a silhouette of Yemmerrawanne (who died in London in 1794) and a tiny portrait of Bennelong, showing him in the cravat and spotted silk waistcoat procured for him from a fashionable tailor. This image of Bennelong, in disparity to that by the Port Jackson Painter, seems to suggest a shift in status from proud negotiator to exotic curio. It became the basis for engravings depicting Bennelong in European dress and framed by an arrangement of spears and other artefacts – images which perhaps indicate the discord of someone who had successfully adapted to ‘civilised’ ways, but who was scorned by some British commentators for having ‘resumed all his savage Habits’ after returning to Sydney in 1795.

This tension can be found in a number of portraits made of Indigenous people who continued to occupy both worlds as European settlement consolidated. While interactions between original and new inhabitants became established during the 1790s, the open spirit that Phillip and others had worked to infuse gradually soured. This mood was mirrored in portraiture as, for example, the noble and sensitive ethnographic studies of Sydney people made by French expedition artists Nicolas Martin Petit and Jacques Arago began to exist alongside pejorative images of those degraded by drunkenness and other side effects of contact. By the early decades of the nineteenth century, colonial aspirations were positioning Aboriginal people as obstructive to order and progress. These are values typically associated with Lachlan Macquarie (1761–1824), the man who became governor in 1810 and who is popularly thought of as the first administrator to approach his work in the colony with visions for its development and prosperity. The instructions issued to him underline the change in approach: from that of managing a useful convict settlement to one of shaping and expanding it with education, exploration and sobriety.

In 1815, two years after Bennelong’s death, Macquarie initiated in Australia the practice of issuing gorgets to Aboriginal people who had demonstrated ‘proofs of industry and an inclination to be civilised’. The custom of rewarding Indigenous leaders with these symbols of their worth and allegiance had begun in the eighteenth century, when the holds of explorers’ ships were stocked with medals, nails, beads and other trinkets as tokens, bribes or objects for trade. The practice of honouring Indigenous military allies with gorgets would have been familiar to Macquarie, and to a number of the First Fleet’s officers, from his service in Canada and America. Unlike North America though – where British gorgets and the peace medals issued by presidents often recognised those viewed as leaders by their own communities – the practice in Australia was applied partly as a means of creating a social order that made ‘progress’ more workable for those engaged in its implementation.

As historian Jakelin Troy has explained, while gorgets (also called breastplates or king plates) were seen by some recipients as an honour, ‘an Aboriginal person wearing a gorget was, certainly from the colonists’ point of view, considered to be a leader within the Aboriginal community’. Macquarie’s first gift of one of these engraved, crescent-shaped panels of brass was made to Bungaree at the inaugural

feast and meeting with Aboriginal people that Macquarie proclaimed would be celebrated annually from 1815. Although these meetings were eventually abolished, the habit of creating so-called kings, queens and chiefs became so useful to pastoralists and white authorities that, by the 1830s, observers such as author Louisa Anne Meredith were reporting that ‘the gift of a brass medal, formerly a rare distinction, is now made so frequently that the honour of the badge is somewhat diminished’.

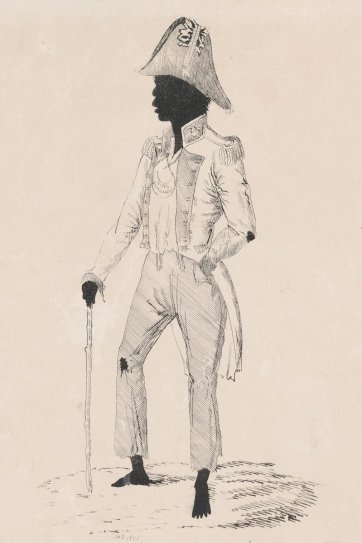

The custom, which continued throughout the nineteenth century and into the early years of the twentieth, was recorded in numerous portraits and photographs, often most powerfully so in the images of Bungaree, the best-known Sydney Indigenous identity of the Macquarie period. A man of Guringai descent, Bungaree (d. 1830), came to Sydney from Broken Bay in the 1790s and, like Bennelong and other Aboriginal men, used acquaintanceship with the British as an opportunity to explore new territory. In 1799, he travelled as far north as present-day Brisbane with Matthew Flinders and joined him again in 1802 as a member of the Investigator expedition, thereby becoming the first Aboriginal person to circumnavigate Australia. In 1817 Bungaree joined Phillip Parker King on his survey of the Australian coast and it was in part for such services as a sailor, go-between and guide that Bungaree was rewarded with the breastplate bearing the title Chief of the Broken Bay Tribe. Other accounts, such as that provided by the visiting Russian explorer Faddei Bellingshausen in 1820, illustrate that Macquarie also valued Bungaree for his skills as an intermediary and as an example by which others might be encouraged to adopt civilised ways. ‘Wishing to turn the natives of New Holland from their nomadic existence and to accustom them to a fixed abode’, Bellinsghausen explained, ‘Governor Macquarie had given Bungaree a specially built little house with a garden’, as well as a fishing boat, clothes, and farming equipment. Bellingshausen’s expedition artist Pavel Mikhailov, Phillip Parker King and silhouettist William Fernyhough are among several artists known to have created portraits of Bungaree – arguably the most-documented Aboriginal sitter of the time. The likeness painted around 1826 by Augustus Earle (1793–1838) is the best known of these representations. An adventurer as well as an artist, Earle’s output during almost three years in Australia encompassed scenes of settlement life, landscape and reportage as well as portraiture. He depicted Bungaree dressed in a second-hand military uniform, hat raised in welcome to visitors to ‘his’ country and with the headland that had been the site of the brick house built for Bennelong as his backdrop. Earle’s painting became the subject of the first lithograph produced in Australia – making Bungaree, in a way, the subject of an early Sydney Harbour souvenir.

Despite this, Earle’s portrayal did not attempt to mask the matter of Aboriginal lives and traditions being affected by European presence. In capturing Bungaree’s proud display of the gorget gifted to him by Macquarie, Earle and other artists created a visual record attesting to the complexity of relationships between settlers and Aboriginal people in the first few decades of European settlement. Images that absorbed the patterns of understanding and puzzlement, tolerance and tension; and that link early Australian portraits with those collected in and of places and people irretrievably changed by their encounters with eighteenth-century Britain.