Goldfields towns, by certain accounts, were no places for wallflowers. Rough-shod, boorish and beset as much by discontent as by fortune, they have been described as places avoided by all but the most intrepid of women.

Those women that did brave the goldfields, though, saw opportunities for themselves there, whether in the expected roles of helpmeet and housekeeper or in more independent and lucrative categories. They went for the better wages paid for domestic work, to open businesses as shopkeepers or dressmakers, or in the hope of scoring a newly wealthy man to marry. Some made money with pubs, sly grog and other enterprises typically patronised in towns peopled mainly by men. And then there were entrepreneurial women like Lola Montez, who came to Australia to seize her own particular share of its fresh, goldgenerated wealth.

It is difficult to discern fact from the numerous fictions that cling to Lola Montez, the Irish-born dancer of faux Spanish heritage who packed an exceptional inventory of experiences into the four decades preceding her death in New York in 1861. Her life up until the time she arrived in Australia in 1855 had seen three marriages, two divorces, a charge of bigamy, the death of one lover in a duel and the demise of others in equally dodgy circumstances. Known for an ‘unwomanly’ degree of short-temperedness – a mean hand with a horsewhip who allegedly packed a dagger in her petticoats – she was equally renowned for a distinct want of propriety in her personal life that had raised obvious questions about her sources of income. In addition, Lola had danced in theatres on two continents and along the way become famous for the loveliness of her looks and the lewdness of her performances. As one witness put it: ‘Her beauty, of rare, voluptuous fullness, is beyond any criticism. Her dancing, however, was no dancing at all but a physical invitation.’ Local memory has likewise been inclined to see her mainly as a saucy sideshow: a famous performer who alternately seduced and scandalised audiences during her year-long Australian tour.

Born Maria Dolores Eliza Rosanna Gilbert in 1818 (although accounts of her year of birth differ), Lola Montez spent her early years in British military outposts in India and her later childhood in England. When, in 1837, her mother attempted to marry her off to ‘a rich and gouty old rascal’, Lola eloped with a soldier named Thomas James. The marriage, as Lola termed it, was one ‘almost sure to end in a smash-up’, and her happiness with the unfaithful James was short-lived. Soon after leaving him, Lola engaged in a shamelessly unconcealed affair for which transgression James later successfully sued for a judicial separation. Outed as an adulteress, Lola went Spain where, having decided to earn her living on the stage, she received some form of tuition in dance, picked up a passable command of Spanish and fashioned for herself a new, untarnished identity. She returned to London with a racier name and, largely through the deployment of wiles, succeeded in securing her debut at Her Majesty’s Theatre in June 1843. Her stage appearances created a sensation but it didn’t take long for London to cotton on to her fake Spanish credentials. She fled again and over the next several months performed in cities including Berlin, Warsaw and Paris. Lola’s looks and stage presence, however, were little compensation for insubstantial talent, and her performances were mocked by critics. ‘We could say that Mlle. Lola has a small foot and pretty legs’, wrote one Parisian observer in 1844, but ‘as for the way she uses them, that’s another matter.’ By 1845, Lola was in Munich. Here, King Ludwig I of Bavaria – three decades Lola’s senior and a known philanderer despite his thirty-six year marriage – saw her dance and fell for her.

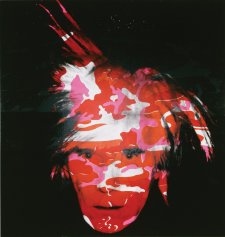

Ludwig soon afterwards commissioned court painter Joseph Karl Stieler (1781-1858) to paint Lola’s portrait – the first of a number of portraits of her made to the king’s orders. Stieler’s second attempt at Lola’s likeness, painted for Ludwig’s ‘Gallery of Beauties’ at Nymphenburg Palace in Munich, has become the most famous of the numerous images made and circulated of her throughout the 1840s. Some representations of Montez satirised her want of talent and some were openly vulgar and pornographic. Others were intended simply as souvenirs of her beauty and status as an object of desire: the portraits which document the lovely eyes and ‘raven hair’ routinely noted by contemporary commentators; and those which, despite her deep and well-documented ability to be coarse and vituperative, depict her as demure and graceful in her trademark mantilla and curls. Stieler’s surviving portrait of Lola, and that supposedly painted by Friedrich Dürck (1809- 1884) around 1845 – acquired in 2010 by the National Portrait Gallery – occupy this latter category and were among the lavish honours Ludwig settled on his lover, despite her being largely loathed and mistrusted by his government, court and people. Ludwig’s sadly slavish attachment to Lola continued amidst unrest at her political influence. In 1848, Ludwig yielded to demands for Lola’s banishment and then abdicated. Lola was forced to flee again. She went back to performing for a time before leaving for the Californian goldfields in 1850. When, after five years, America lost its profit-making lustre, her attentions turned to Australia.

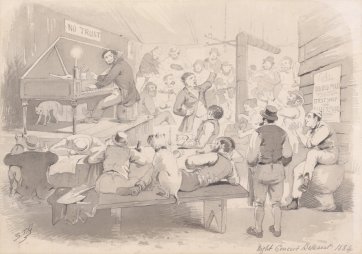

Lola’s experiences during her time here present a mirror to the contradictory ways in which the Australian colonies responded to gold-rush upheaval. On the one hand welcomed for its extraordinary economic blessings and marvelled at for the rate at which towns and industries developed in its wake, the discovery of gold was also greeted as a monster of a moral curse. Violence, booze, prostitution, men deserting wives and families for the diggings: all were among the feared and proven effects on respectable society of a population engaged in the obsessive pursuit of mammon. ‘Alas! for poor human nature’, witnessed English author Elizabeth Ramsay-Laye of 1850s goldfields life, ‘most of the wives in the camp exhibit on their faces the brutal marks of their husbands fists! Many of the diggers have reduced themselves to mere savages from the effects of drink … Hence drunkenness and all its concomitant evils are terribly prevalent at the diggings, and gin-palaces are there the most profitable of all speculations.’ This mixed character of gold rush existence is often confirmed in the work of artists such as ST Gill (1808-1880), who left Adelaide for Victoria in 1852. Finding more inspiration in his surroundings than in prospecting, Gill took to recording every aspect of goldfields life – industrious diggers as well as the despondent and dissipated ones – in drawings often noted for their wryness and wit. Gill was one of a number of artists who capitalised on the prosperity and social complexity generated by the discovery of gold. Opportunities for performing artists expanded also and Lola Montez, a prime exponent of an art form that thrived on reinvention, made perfect material for booming theatres and music halls. At the same time, she embodied official anxieties about immorality: anxieties underlined in the ardent or puritan ways in which people responded to her.

She made her Australian debut at Sydney’s Royal Victoria Theatre in August 1855, appearing in ‘Lola Montez in Bavaria’, a burlesque recalling her time in Munich. The Sydney Morning Herald reported that she was received ‘with an enthusiasm never equalled’ in that theatre, but the season regardless returned to her established pattern of sensation quickly superseded by scandal. Faced with a warrant for unpaid debts, Lola and her manager-lover decamped to Melbourne. A week after her first appearance at Bourke Street’s Theatre Royal, her ‘Spider Dance’ began to generate calls for her arrest. ‘We feel called upon to denounce, in terms of unmeasured approbation, the performances in which that lady last evening figured’, preached the Argus of 20th September 1855, ‘and if scenes of the kind are ever to be repeated, we consider that the interference of the authorities is imperatively called for to put them down as a nuisance, and as utterly subversive of all ideas of public morality.’ With prudish Melbourne no longer welcoming she went to Adelaide and performed to full houses. By February 1856 she was on the goldfields: first Ballarat, then Bendigo, Castlemaine and other towns where her shows were a popular and ribald release from diggings life.

First hand accounts of her Australian appearances, however, are inconclusive on the true degree of their indelicacy. According to Celeste de Chabrillan (1824-1909) – wife of the French consul-general, an acquaintance of Lola’s Paris days, and shunned herself by Melbourne society for her demi-monde past as a courtesan and danseuse – the Spider Dance consisted of Montez ‘moving about a lot while frantically shaking the folds of an extremely short gauze skirt’ in which a spider had supposedly concealed itself, the routine’s climax being the beast’s discovery and immediate death from a flamenco-like stomp of Lola’s pretty foot. De Chabrillan, with insouciance, declared it harmless: ‘I don’t know why, but all the women walked out before the end of the ballet, although there is nothing improper in it.’ Elizabeth Ramsay-Laye tells us that Lola attracted attention for her ‘startling’ beauty – ‘her eyes especially, were so remarkable that one forgot almost to notice the other features of the handsome face’ – but that no ‘ladies’ risked the taint of seeing it on stage. In Adelaide, solicitor and artist John Michael Skipper (1815-1883) saw Lola perform. His tiny, sketched record of the encounter shows the Spider Dance as hardly saucy, although his drawing of Lola ‘In the green room’ documents an unladylike, come-hither posture and her established disregard for convention on the issue of women and smoking. In Munich, for example, she was known for her smoking and beer-drinking parties and in America she’d had herself captured, cigarette in hand, in a daguerreotype by the Boston photographers Southworth & Hawes – said by one of her biographers to be the earliest photographic representation of a woman smoking. It followed, then, that savvy impresarios were happy to exploit her reputation and Lola herself was an able manipulator of it, knowingly creating publicity for herself and material for her detractors: taking to the editor of the Ballarat Times with a whip, for example, when he published a slanderous review; fighting the wife of a theatre manager; and abusing hecklers.

In July 1856, perhaps tired of Australian provincialism, Lola returned to America. When her stage career stalled the following year she toured America and Britain delivering a series of lectures on beauty and morality. Whether a genuine renouncement of her wicked ways or a means of twisting them to new advantage, the lectures, published along with her ghostwritten autobiography in 1858, offered a vigorous defence of her life and a rebuke to her libellers. ‘Such is the social and moral fabric of the world’, she explained, ‘that a woman must be content with an exceedingly narrow sphere of action, or she must take the worst consequences of daring to be an innovator and a heretic.’ The lectures echoed Lola’s earlier assertion that her choices had been dictated by conditions which forced women ‘to achieve our goals by whatever is available to us, even when we recognise that we are thus put in an unflattering light.’ The personal consequences for Montez, most particularly her death from syphilis at forty-two, were indeed sobering, while the consequence for history has been a record focussed almost exclusively on her notoriety. Consequently, Lola Montez’s presence on the Australian scene has been much remarked upon, but often by those too steamed up by her beauty and brazenness to assign her much more than a flimsy significance. The acquisition of her portrait for the National Portrait Gallery, however, accords her an alternative category for consideration: not merely the foxy, feisty strumpet of popular memory, but a figure exemplifying specific moods and shades in Australian experience during a defining decade.