At its first meeting on 4 March 1998, the Board of the National Portrait Gallery agreed to build a national portrait collection. At its second meeting three months later, the Board approved the very first purchase of a portrait for the collection: Jenny Sages’s Emily Kame Kngwarreye with Lily.

The purchase of the portrait of the great painter was a blunt declaration, at the outset, that the Gallery would not be stuffed with portraits of ‘dead white males’, company directors and prime ministers. The tiny, wizened woman faced the portraitist with no pretensions, and Sages portrayed her literally grounded, sitting cross-legged in the quintessential Australian landscape of her country. The oil portrait of Emily is one of four large portraits of women by Jenny Sages on display in the Marilyn Darling Gallery over spring and summer. The others, made in the challenging medium of encaustic and pigment, are three other sage, senior women: the author Helen Garner; the late prima ballerina Irina Baronova; and the artist herself.

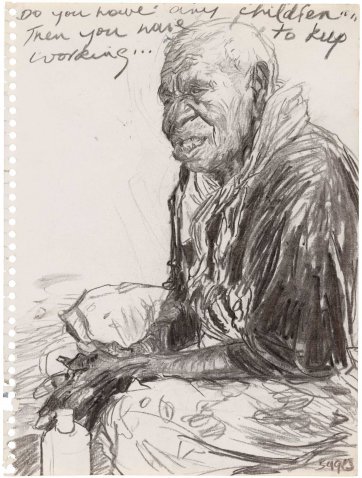

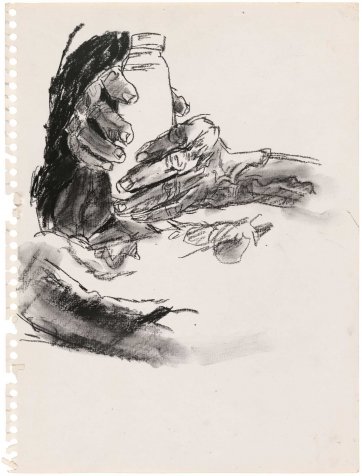

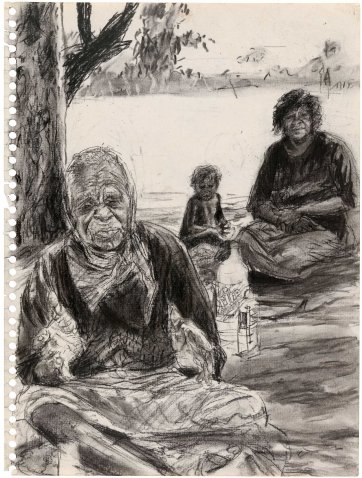

A delightful advantage to the Gallery in acquiring the portraits of Kngwarreye, Garner and Baronova is that alongside the finished works, Sages donated sketches she made as the portraits began to take shape in her imagination. Never before exhibited, these fine drawings are a highlight of the exhibition, offering an uncommon insight into the portrait process.

Drawing her ideas is as natural to Jenny Sages as speaking. Her inquisitive, intelligent and effusive personality is woven through her works, which have come about through her long accretion of experience. They reflect the time she has spent walking the country; her compulsive reading; her fateful meetings; and her exploration of her own Russian background. Sages was born in Shanghai to Russian Jewish parents. When she was fifteen, her family relocated to Australia. After a restless period at East Sydney Tech, she left for New York, where she went to art school, greedily inhaling the exhilarating atmosphere of the times. Three and a half years after having left Australia, she was on her way back when she met Jack Sages, the handsomest man she had ever seen. They spent five heady days and nights together before she came home to her parents. A year and a half later, she was to marry Jack; their daughter, Tanya, arrived in 1968. Meanwhile, beginning with a series of drawings for fashion retailer Mark Foys, she had established herself as a commercial artist, illustrating magazines and books. For three decades she drew fashion, travelled on assignment, and wrote about and drew the places she visited.

In 1983, at the age of fifty, Jenny Sages went to the Kimberley, and her old life simply fell away. Soon, she was to give up illustrating publications and become a full-time artist, concentrating on abstract and landscape works. For more than twenty years she went out annually to ‘walk the land’ with a core group of five regular companions, joined, sometimes, by other congenial women. As Sages describes it, they would ‘kind of glide’ through the desert, seeking out its secrets without braggadocio, posing no threat. On one of her early expeditions, she arranged to meet up with Emily Kngwarreye. Having charmed her way onto a plane with some German curators, she had to wait for four days for the older woman to turn up with her mob. Sitting with Kngwarreye, Sages poured her impressions onto paper, annotating drawing after drawing with her sitter’s observations and, eventually, protestations. Back in her Sydney studio, she developed the huge, spare painting that became a foundation work for the nascent Portrait Gallery. In 2001, Sages met Emily’s niece, painter Gloria Petyarre, who was living at Utopia by then. Having thought about it for some years, Sages painted a portrait of Petyarre in her much-loved country that became a finalist in the Archibald Prize of 2005. Exhibited concurrently, Sages’s painting depicting the way to Petyarre’s home, The Road to Utopia, won that year’s Wynne Prize for landscape.

Sages’s self portrait Each morning when I wake up I put on my mother’s face was made in 2000. This painting is unusual amongst the four in Paths to portraiture in that the artist made no preparatory drawings for the work. She made it directly, referring only to the mirror as she laid it down. She felt uncomfortable about representing herself, which explains why she is shown in a characteristic anxious pose, tightly gripping her own delicate frame; and why her figure is pushed to the extreme periphery of the composition. The resulting empty space is covered with words from the Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, which struck the artist as an apposite way in which to veil, and yet indicate, her own history. Sages scratched them over and over again into the surface, thinking, as she did so, of Russian intellectuals who committed works of literature to memory in a time when being caught with books could mean death. For the National Portrait Gallery exhibition, Jenny Sages has brought together materials that fed into, and resulted from, the self-analysis inherent in her portrait. It includes her volume of Akhmatova’s poems, fatly flagged.

By the time Sages made her first overture to Helen Garner, in the mid-1990s, she had resolved to paint only one portrait a year. Though her works were in demand, she had not adapted comfortably to the idea that she was in a position to pick and choose her sitters. Conscious of her boldness, she wrote to Garner, whose True Stories she had admired, and suggested a painting of the author with her sisters, who feature in that book. Garner quickly, and frankly, put paid to that idea, leaving the artist feeling rather sheepish about her own ‘delusions of grandeur’. Seven years later, in 2002, she approached Garner again; they met in Melbourne, many sketches were made in various mediums, and a strong portrait of the author evolved. A sketch in the exhibition shows that for a time, Sages considered inscribing the words ‘true stories’ on the portrait, but she decided against it, and incorporated them into its title instead.

Encaustic and pigment, which Sages uses brilliantly in her abstract work, is a treacherous medium that translates somewhat uneasily to portraiture – although many of the exquisitely detailed ‘Fayum mummy portraits’ of Egypt were made this way two thousand years ago. She describes how, for the portrait of Garner, she lightly laid down the fundamental elements in wax and red pigment. ‘Then, with my heart in my mouth,’ she writes, ‘I dipped my fingers into the wax medium and then into the pigment. Using my fingers as a brush, I just hoped for the best … It was either right or wrong, no fiddling around. Wrong meant scraping the whole thing off with a knife and starting again.’ It was right; and the Gallery acquired the work in late 2004.

Having seen a documentary by the filmmaker Catherine Hunter, Jenny Sages determined to meet Irina Baronova, one of the three ‘baby ballerinas’ of the Ballets Russes who had toured Australia in 1938-1939. In 2006, the artist travelled to northern New South Wales to visit her daughter, Tanya (the subject of Sages’s evocative series Red shoes from Vinnies, exhibited in the recent National Portrait Gallery exhibition Idle hours). By then, Baronova was living in Byron Bay, near her own second daughter, and the two mothers met there. Sages was enchanted by Baronova’s aristocratic deportment, even as she was reduced to helplessless laughing at her scurrilous Russian asides. Later that year, in Melbourne, Sages watched the still-beautiful Baronova coaching young ballerinas in roles that had been created for her by Fokine, and drew the rehearsing dancers as she looked on. As was the case with the portrait of Garner, a drawing she made translated faithfully into the finished work. Sages and Baronova remained friends until the ballerina died in 2008. The artist still misses the older woman’s telephone calls, when she would hear in her lilting ‘hello darling’ the echo of her own Russian mother’s voice.

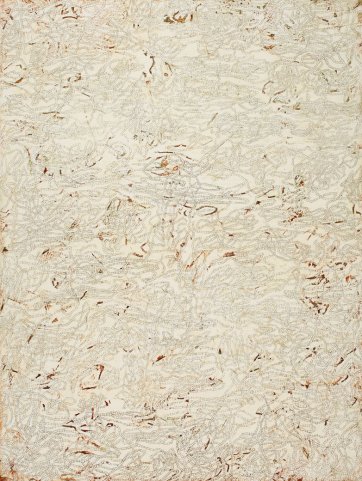

On one of Sages’s wonderful series of sketches of Emily Kngwarreye, she noted something the Anmatyere woman said to her: ‘Do you have any children? Then you have to keep working.’ Sages has kept working, and it is hard to think of a greater gift she could bestow on her daughter than the effulgent portrait of their respective husband and father, Jack, that she made earlier this year. Few people are in a position to possess a radiant representation of one parent made by the other when both were comparatively advanced in age. Currently preparing a suite of intriguingly textured and minutely detailed abstract works for commercial exhibition, the artist has generously lent one she made for this purpose for exhibition at the Gallery.

Curators and educators at the Gallery have long discussed the possibility of an exhibition examining the portrait process. This one – an irresistible choice given the artist’s unique seniority in the collection, and the strong body of drawings that she has donated – reminds us that in the collected work of many of our most interesting portrait artists, figurative works comprise but part of the picture. Nearly everything in Sages relates to the Gallery’s mandate; but the exhibition as a whole affords beguiling proof that the process of portraiture can be far more than a matter of adumbrating and reworking the sitter’s face.