Throughout the winter of 1881, Sydney newspapers reported on an outbreak of smallpox that supposedly started with the infection of an infant whose father was a successful George Street merchant. That this child’s father was also Chinese was enough for some to label smallpox a ‘Chinese disease’ and by implication cast Sydney’s Chinese population as the cause of a whole package of problems.

Gambling, opium addiction, corruption and immorality. As the scapegoats for such evils, Chinese people were subjected to persecution – from unofficial and official sources. In 1881, the New South Wales government declared that all Chinese ports were ‘infected’ and enacted legislation restricting the immigration of Chinese people to the colony. In the midst of this though, one Chinese-born man experienced a very different variety of reception in Sydney. In September 1881, Quong Tart – well-off, well-connected, thirty-one years old – had just returned from a visit to China. A month later, the same papers that had peddled paranoia about ‘Chinese disease’ were advertising ‘Quong Tart & Co: Tea, Silk and General Merchants’, the first in a chain of enterprises that by the turn of the century had made their proprietor the bestknown and most prosperous of Sydney’s many Chinese businessmen.

Mei Quong Tart (1850–1903) was an archetypical self-made man. Born in Guangdong, he came to New South Wales with his uncle at age nine, possibly as a scribe to a group of Chinese miners on their way to the Braidwood goldfields. Here, he joined the family of a stock and station agent, Robert Percy Simpson and his wife, Alice, who is believed to have converted him to Christianity. He then worked as an interpreter and, with Simpson’s encouragement, acquired shares in mining ventures. By his late teens he had prospered. In Braidwood, Quong Tart availed himself of distinctly European interests, among them a taste for Scottish songs and poetry (some later nicknamed him ‘Quong MacTartan’) and gentleman’s sports: cricket, cycling, football and horseracing. Aged twenty-one, he was naturalised. It was during his Braidwood years also that Quong Tart began to develop his philanthropic side, contributing funds towards the building of a church and a school, for example, and involving himself in community associations. When he returned to China in April 1881 it was with testimonials signed by ‘members of Parliament and other leading residents’ and was thereby more than a family visit. Quong Tart, according to one report, spent some of his time in China ‘addressing gatherings of his countrymen on the subject of Australia’, presenting himself as ‘proof of the fact that any individual in this free country may gain the respect of the public, provided his behaviour merits it, no matter to what race he belongs.’

In Sydney from 1881 onwards, Quong Tart became famous both for his businesses and his involvement in charities and civic causes. His first venture introduced to Sydney tea-drinkers the concept of try-beforeyou- buy and was so popular that a series of fashionable tearooms followed. By the time his flagship ‘Elite Dining Saloon’ opened in the Queen Victoria Markets in 1899, Quong Tart had operated tearooms in the Sydney and Royal Arcades, in Haymarket and King Street, and in the zoological gardens at Moore Park. His tearooms were pitch perfect places for ‘ladies’ who eschewed taking refreshment in pubs or cafes, as well as being a ‘popular resort among businessmen’ and other city types. Although his social standing precluded Quong Tart’s being regarded by many Chinese people as a representative, he seems to have seen himself in this role. In numerous instances – whether mediating in disputes between Chinese and non-Chinese, or fostering mercantile opportunities between home and homeland – Quong Tart was an advocate for the interests of Chinese people, perhaps most notably in his efforts to put an end to the opium problem. His views – such as those stated in his 1887 Plea for the Abolition of the Importation of Opium – sometimes echoed the tone of anti-Chinese cant, yet his campaign was conducted with the dignity and reputation of his compatriots in mind: an effort to prevent all being caught within stereotypes about Chinese predilection for vice. The government too consulted him on a number of issues pertaining to Chinese people, appointing him to the inspection of Chinese settlements in the Riverina in 1883 and to the 1891 Royal Commission into ‘Alleged Chinese Gambling and Immorality’; and later proposing him for the position of Chinese Consul General.

Quong Tart’s outwardly ‘British’ style of life no doubt smoothed his way to acceptance during times so marked by anti-Chinese feeling. Yet he never obscured his Chinese heritage. Instead, he created for himself an adaptable identity, one that honoured Chinese culture and at the same time enabled him to flourish in local social and business conditions. His private life perhaps best demonstrated this adaptability. When he married in 1886, he ignored his mother’s selection of ‘several Chinese women of distinction who would willingly have accepted him’ and wed English-born Margaret Scarlett (1865-1916) instead. Quong Tart observed the Anglican religion but had each of his six children baptised under different denominations. His home life at Ashfield’s Gallop House, where the Tart family lived from 1890, demonstrated an easterninfluenced western gentility. Quong Tart saw himself as both a Chinese dignitary (he was made a Mandarin of the fifth rank in 1888 and elevated to the fourth rank in 1894) and a typical Australian ‘gentleman’. Margaret Tart’s biography of her husband – The life of Quong Tart, or, How a foreigner succeeded in a British community – describes him, for instance, as a ‘patron … of every manly sport’ and lists his membership of groups as diverse as horticultural societies, hospital funds, bowling clubs and the ‘League of Wheelmen’. It also notes Quong Tart’s expressed wish that his children would know that ‘although their father was a Chinese, he could creditably be compared with thousands of European fathers.’ On his death in July 1903 he was indeed remembered as ‘a good citizen’ and ‘a kind of connecting link’, respected by both the ‘Chinese citizens and the general community.’

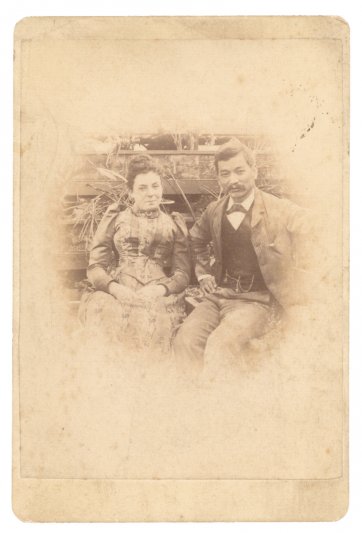

His consciousness of presentation and posterity is evident in the images of him and his family now residing in a selection of Sydney collections. One of the most intriguing of these portraits, presumed to date from the 1880s, is currently on loan to the National Portrait Gallery from Sydney’s Mitchell Library. The painting, like many photographs of Quong Tart, shows him as dapper and confident but is also a work which bears the somewhat unsettling quality of a portrait painted from a photograph. Photography, while the most popular and accessible format for portraiture in the late nineteenth century, was still viewed as painting’s poorer, tawdry relation. So studios adapted, offering patrons the option of tinted photographs and those which had been painted over. Other companies acted as agents for Asian studios specialising in copying and enlarging cartes de visite as paintings. This was a service offered by businesses such as Sue, Hing Long & Co, the Sydney agents for the Chinese and Oriental Photographic and Oil Portrait Company, located in Hong Kong. Through the 1880s, Sue, Hing Long operated from an address in The Rocks and from one close by to Quong Tart’s premises in the Sydney Arcade. Quong Tart himself dealt in these uncanny objects, advertising his company in October 1881 as an agent for ‘photographic paintings in oil, life size. Finest quality.’

Authorities on Quong Tart’s history have noted his use of portraiture and the success with which he employed photography to assert himself as gentleman and even a celebrity. Quong Tart has also been argued to have used photography as the means by which he distinguished himself from competitors in a consciously-created record of the ease with which he moved across cultural boundaries. Photographed with his cricket team or his well-dressed wife and family; portrayed with his racehorse; documented with associates and employees; and just as often depicted with the symbols of his Chinese status and origins. His successes were aided by this profile. But portraits of Quong Tart read not just as devices with which he built and maintained a sense of his importance and prosperity. When viewed from a century’s distance, they are strong ripostes to the derogatory images of Chinese people which were freely purveyed in his lifetime. They are potent images of a complex individual whose successes were all the more elegant for their emergence in a city and a time often laced with ugly sentiment.