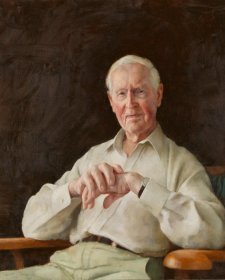

In September 1937 Maurice Lambert wrote a very direct letter to the publisher Sydney Ure Smith regarding Amy Lambert’s memoir Thirty Years of an Artist’s Life, then in preparation: In no circumstances whatever will my mother countenance the use of the self portrait with dressing gown as a frontispiece. A more insane idea than that I never heard. This book is about a man, do you understand? The brilliant piece of technique with which he disguised from the mediocre but revealed to the sensitive just what a few years in Australia had done to him is not what this book is about.

In Maurice’s remonstrance there are echoes of the line that infuses his mother’s book – that Australia not only broke up a family but killed the artist. But there is a sense, too, in his words that Australia unmanned the artist – that it brought out an effete quality, warmed the idea that he was a hot-house rarity – or as he put it himself, ‘a Chippendale chair in a country where timber is cheap’. Maurice’s reading – and it was doubtless Amy’s reading of the painting, too draws our attention to the self portrait’s ambiguity, its strangeness and its inherent sense of strain. In general, critics’ response to Lambert in the 1920s mixed deprecation of his mannerisms equally with appreciation of his dexterity.

The stagy portrait is the very embodiment of the idea floated by a journalist in 1922 that Lambert ‘dearly loves a pose’. The pose’s lack of logic was picked up by perceptive commentators – including Hans Heysen – who didn’t think the parts of the portrait fitted together. In general, commentary on the portrait implies that Lambert’s gesture served purposely to demonstrate the artist’s technical and analytical skill. Julian Ashton summed up the widespread feeling in 1924 when he wrote that he would not quarrel with Lambert’s affectations ‘as long as they are painted as well as that’.

The first striking aspect of Self portrait with gladioli is a certain peculiarity about the composition. The space in the painting is seemingly very shallow and the blooms are crowded into the foreground corner, seeming to fall against the front of the dressing-gown. Perhaps they were an afterthought. Had they not been included, the lower half of the composition would fall away for there is certainly no curvaceous stomach to fill out that part of the picture. Lambert’s determination to avoid what he considered a basic compositional fault – to have a diagonal running out of the corner of a painting – accounts for the broken angle of the stems and their rather throw-away disposition in the crystal vase.

The hands in the Self portrait with gladioli are very conspicuous. Hands were the focus of Lambert’s most famous exercise in virtuosity – the drawing Left and Right of 1925, which includes another self portrait. It is no accident that this self portrait shares a sheet with the bravura exercise of drawing hands. Lambert is telling us that the hand is the artist – and the artist is clearly pleased with his cleverness.

The third notable element in Self portrait with gladioli is the dressing gown. Is Lambert showing himself almost dressed for dinner – about to go out, in French cuffs and cufflinks – or has he come in from another of the dinners that he regularly complained about as a distraction from work? How are we to explain what looks like a second robe, in Thea Proctor’s favoured scheme of violet and white stripes, under the velvet gown?

The 1923 reviewer in the Australasian described Lambert’s getup as a ‘rest robe’ made of ‘greenery-yellow’ chiffon velvet. His readers would have recognised that as an allusion to the effete aesthete of Gilbert and Sullivan’s Patience – the ‘greenery-yallery, Grosvenor Gallery/Foot in the grave young man’. Perhaps that had something to do with the artist’s wife and son insisting that you couldn’t use this picture – which they described as ‘the self portrait with dressing gown’ – to stand at the front of a book ‘about a man’.

In the 18th century, in particular, there is a range of portraits of male sitters in elegant loungewear from which Lambert may have taken inspiration. Whatever else we might see in Lambert’s dressing gown, however, there is nothing about it that connotes the artist’s life as a worker. This is interesting because in January 1922 he often railed in his letters to Amy against interruptions to his work – ‘If only I could be an artist, reckless and irresponsible. The sort of creature that everyone, when he meets me, thinks I am!’ At the same time he was telling the world to forget the notion of artistic genius and concentrate instead on treating artists as tradesmen. This foppish robe is not work-a-day, nor are these hands, like collapsing fans, the tools of an honest labourer.

I believe Lambert had already essayed the artist-as-worker self portrait before he undertook the Self portrait with gladioli. In September 1921 Lambert wrote to Amy that, in addition to a ‘wild dashing portrait’ that became known as The White Glove, he had on the slips ‘a self portrait for Sydney’s new Uffizi Gallery of Australian artists’ portraits’. In 1921 the trustees of the Art Gallery of New South Wales had begun requesting prominent Australian artists to paint self portraits with a view to creating a self portrait gallery on the Uffizi model. Lambert was among the first to be asked and he agreed. But he never delivered. Six years later, when he was besieged with commissions, requests from dealers and reminders of work outstanding, the Gallery, too, wrote desiring to know ‘whether they will have the pleasure of receiving the portrait at an early date’.

I think it is very likely that the self portrait destined for the Art Gallery of New South Wales that he had ‘on the slips’ in 1921 is the unfinished self portrait that was in Lambert’s studio at the time of his death, which was bought by the Gallery in 1930. Traditionally, this has been dated c.1930. However, the features are much closer to those we see in Self portrait with gladioli than in later self portraits such as the 1927 drawing.

There are several reasons why Lambert might have abandoned the ‘Uffizi’ self portrait, which he was expected to donate to the Gallery. He agreed to paint it in July 1921, and had made a start by September. In October, he received a letter from the Gallery in which they set out a preferred uniform size for the self portrait – 20 x 24 inches – which was the size of the one Tom Roberts had already delivered. That is somewhat smaller than the size of this work – 38 x 26 inches, and the disparity may well have been enough to cause Lambert to stop work. Secondly, in late 1921 he was overtaken by paying commissions and so probably lost interest in a painting that was only for the sake of kudos.

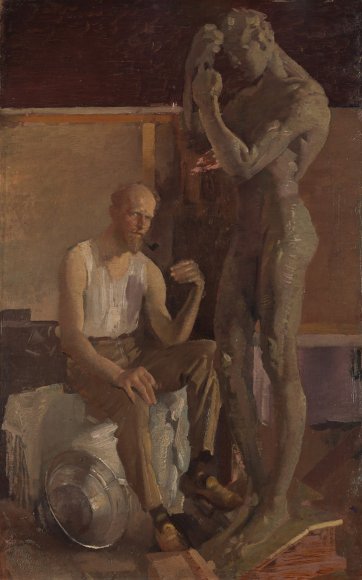

If the date of 1921 is correct – and it is supported by the evidence of the canvas, which is from the same Melbourne supplier as the Self portrait with gladioli – the self portrait makes a very telling contrast with the National Portrait Gallery’s 1922 portrait, which would have been its immediate successor. In the earlier painting, the artist really is a worker. He has the tools of his trade in his hands: brushes, palette and maulstick. Here painting is a shirt-sleeves business – no mystery, no theatricality, just hard effort. Yet the work itself is pedestrian, incorporating neither the intriguing irony of Lambert’s 1920 self portrait The Official Artist, nor the verve and challenge of his 1922 Self portrait with gladioli.

The story of Lambert’s life in the 1920s is one of work, work, work. His letters of the 1920s complain of his relentlessness of effort, and his frustration at distractions. Some of the physical exhaustion resulting from his efforts at commissioned public sculpture, along with other demanding projects, is evident in a small self portrait sketch, again discovered in his studio at the time of his death and probably dating from 1924. Here the thin, singleted artist is seated, dwarfed by the virile upright figure of the sculpted nude and the reversed monumental canvas in the background.

A later self portrait drawing, The Broken Hand, shows Lambert in the sculptor’s studio, surrounded by his assistants, crowded around a fragment of sculpture. The artist is the only one seated, his shoulders hunched over the shattered hand. This drawing, I think, can be read as a metaphor of breakdown.

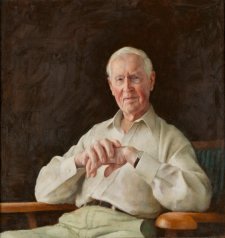

Maurice Lambert’s analysis of Self portrait with gladioli proposes a double meaning to the portrait – one for easy consumption, the other more complex and revealing of whatever it was that Australia ‘did to’ the artist. Certainly, if we compare the portrait with the well-known self portrait of 1909 we can see that Lambert has worn away in the thirteen intervening years. The silky hair has been replaced with a prominent and balding dome. Yet Lambert seems to have enjoyed the possibilities of his skull. He exaggerated its interesting outline even more dramatically in his self portrait drawing of 1927 – a real portrait of middle age in which he peers over the top of his glasses, questioning, wry and sceptical. Apart from the general ‘paring away to the essentials’ of the head, Self portrait with gladioli betrays a striking leanness of body. Although this was the result of Lambert’s malaria, he nonetheless regarded it with some pride. He described the result of one of his periodic ‘overhauls’ in hospital in late 1922 as ‘most awfully fine muscular and brainy condition with figure so graceful that even the Sydney belles are jealous of my proportions’. Four months later he commented ‘I am as thin as a sapling and hard as nails.’ This time, however, he further admitted to being ‘a bit of a ghost, restless and very short tempered’.

The Self portrait with gladioli encapsulates the ambivalence about his return to Australia that had surfaced in the latter part of 1921 and is a constant theme in Lambert’s letters the following year. He expressed it forcefully in a poem he addressed to his wife’s sister in 1922:

‘But you may write a letter to my wife

And tell her all the news you learn of me,

My butterfly existence in this town

Which now unrolls the carpet red

And gives a tribute grudgingly to me

Who after all these years of exile comes,

Like dog to vomit, and mark you, alone,

To his own town, to smell the smells of youth,

To sit and snarl a challenge to the pack,

Or, wagging, grin a welcome to the few,

To those who like yourself, appreciate’.

Self portrait with gladioli is the ultimate ‘snarl and challenge to the pack’ – an expression of attitude that became especially meaningful after Lambert’s election as an Associate of the Royal Academy in November 1922. He succeeded in sending the work to London in 1924 for display there, writing ‘Australia will of course expect great things and excitement when my self portrait is exhibited in the RA but I am too old a campaigner to expect either excitement or even a just appreciation. I just say it was my big effort and it cost me dearly in money and swat.’

It is not surprising that after his death the family associated the Self portrait with gladioli with Lambert’s demise. It was clear that what Lambert had intended as an ‘Australian visit’ in 1921 had become a permanent return. Australia had him and would keep him – alternately fêting him and working him, inflating and knocking him down, until he died.

As much as he loved to attitudinise, even he succumbed to the truth that every artist and sitter knows: one can’t keep up a pose for ever.