Hal and Kate Hattam’s association with the modern art scene was a distinctly Melbourne experience. Yet they championed many artists, several of whom have made a significant contribution to the broader history of Australian art. It is fitting then they are represented in the National Portrait Gallery by two such artists – Kate, painted by Clifton Pugh in 1956 and a 1960 portrait of Hal by Fred Williams. The portrait of Kate is characteristically Pugh. Elongated fingers, drooped shoulders in his favoured ‘egg’ form and angular facial features are a starkly colourful interpretation of likeness and character. The work was painted pre-Archibald Prize success and before Pugh had established himself as a leading portraitist. It demonstrates all the ambition and confidence of an artist breaking away from the tonal training he received under Sir William Dargie, instead formulating his own distinctive style of portraiture.

The abstract background of the painting of Kate is similarly employed in Pugh’s 1957 portrait of ceramicist Tom Sanders. Pugh reflected on the Sanders painting, ‘in those days I was under the influence of Kandinksy’ and he also wanted to ‘paint the chaos around him’. Both of these portraits are reproduced in Involvement a publication that depicts a subject as interpreted through the paintings of Pugh and the photographs of Mark Strizic. Intriguingly, Strizic included both Sanders and Kate surrounded by their children, Pugh did not. Kate, a mother of four children is not depicted in the painting in her maternal role, but instead appears as a shrewd business woman. Her piercing blue eyes, styled hair and medallion jewellery suggest a determined and fashionable woman. Pugh generally found women between twenty-five and forty-five ‘so aware of the image that they are producing that they are difficult to get inside. This is a rare one done in that period, but then of course, I knew Kate so well. It was a picture I wanted to do’.

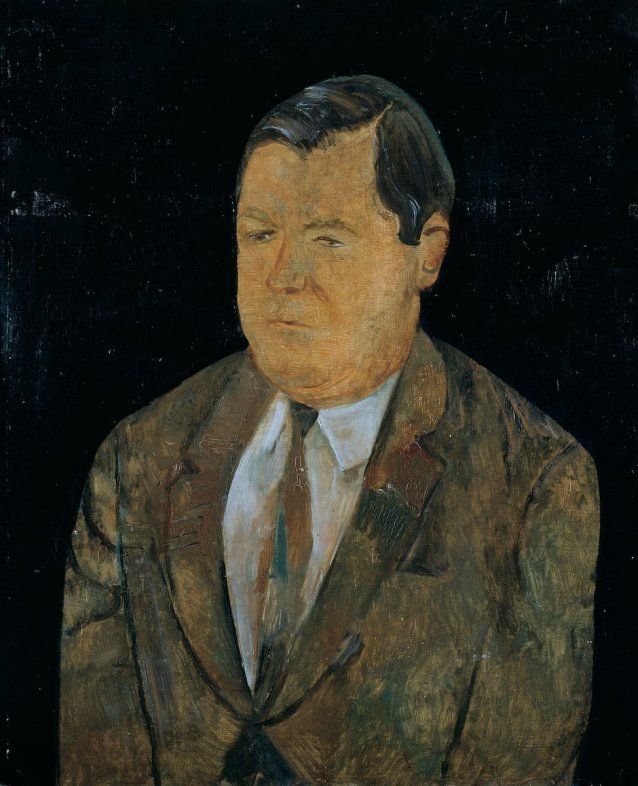

Kate and Hal regularly saw the Pughs at the beach at Shoreham, where each family had a house. The coastal location featured in Hal’s later beachscape paintings. Despite the personalised and intimate experience of a shared holiday location, Pugh has ensured Kate appears as a businesswoman and arts patron. Fred Williams has also depicted Hal in his profession as a medical practitioner and arts patron, not the artist he desired to be. The drab mottled suit and tie, crisp white shirt, emotionless facial expression and neat comb-over hairstyle are formal and impersonal. Williams has employed his usual painting approach of flattening the form against the picture plane, itself an uninspiring black background. Williams painted Hal on more than one occasion, a gesture indicative of a close relationship between artist and patron, painter and painter. Yet, the portrait gives no indication of Hal’s own longing as an artist, rather a blunt separation of professional and personal life.

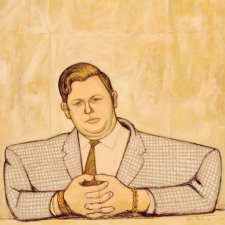

It is this quality that is captured in a 1965 portrait by another artist friend, John Brack. Hal is a solid, suited and stern figure in utter contrast to the boldly coloured wooden floor and richly textured rug. His face and upper body are masked by a dark shadow. As art historian Sasha Grishin has observed this veil ‘serves both to make a broader comment on the depression and anxiety faced by Dr Hattam as well as to make a broader comment on the universal state of anxiety, a feature of the human condition’.

The relationship between Brack and Hattam was also a perceptive and informing two way interaction of shared ideas and experiences. Hal remembers the occasion he was driving Brack to the pub for a drink when the artist ‘pressed the button for the glove box accidentally and out spilled a whole lot of scissors, surgical instruments onto his lap and that started him painting surgical instruments and looking into windows for orthopaedic devices’. Both Williams and Brack offer convincing portraits of Hal that seem to reinforce the notion of art patron and medical practitioner drifting between a current career and a potential future as an artist. Poet and critic Chris Wallace-Crabbe’s interpretation of Hattam’s beachscapes suggests they ‘bespeak the struggle to escape from a medical life, striving towards Bachelard’s world of reveries; gradually making himself an inhabitant of that margin, the sea’s fringe’.

In 1966 the Hattam family moved to 38 Cromwell Road, South Yarra, a relocation that coincided with Hal’s sell-out solo show at the Joseph Brown Gallery. As Patrick McCaughey revealed in his aptly titled essay ‘Hal Hattam and the landscape of longing’, in the new home ‘as the walls filled with paintings, so the rooms filled with artists and writers, critics and curators, fellow collectors and polo players’. It generated an atmosphere where ‘people flitted in and out, unannounced and self-invited.

Red wine was generously dispensed and arguments about painters and paintings, the foibles and foolishness of the art world, were ceaseless’.

The portrait Kate Hattam by Clifton Pugh and Hal Hattam by Fred Williams are recent acquisitions to the National Portrait Gallery and a wonderful summation of a couple of characters who excelled in their profession of medicine and advertising, but also played an important role as patrons of modern art in Australia.