The name of Florence Broadhurst, one of Australia’s most significant wallpaper and textile designers, is now firmly cemented in the canon of Australian art and design thanks to a recent posthumous revival of her designs, two books and a film about her life and mysterious death. This close attention, in turn, has reignited public interest in her fascinating life story.

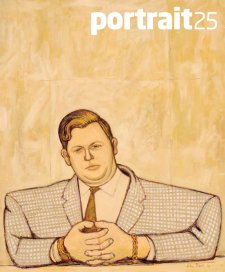

The National Portrait Gallery has recently acquired a 1968 portrait of Broadhurst by her mentor and painting teacher Joshua Smith – the first of his works to enter the collection. Undeservedly Smith is most often remembered as the subject for the 1943 Archibald Prize-winning work by William Dobell that was denounced as caricature, sparking Australia’s first large-scale art scandal, ensuing court case and public debate about objective versus subjective portraiture. Despite this uncalled-for notoriety Smith remains a significant figure in the history of Australian traditionalist portraiture.

Born in 1899 to a modest, yet later landowning family in rural Mount Perry, Queensland, Florence Broadhurst was always determined to make something of her life and knew that to do so she had to leave home and family behind – preferably as quickly as possible. At a very young age Florence and her sisters were offered piano lessons and it became clear that Florence had talent, good keyboard skills and a clear contralto voice. Soon she was travelling by train to Bundaberg, sixty-six miles away, for personal singing lessons. Performing for family and friends clearly did not satisfy her for long and her first public performance was at the Grand Patriotic Concert in Bundaberg in August 1918 – yet a solo singing career never eventuated. Plan B was swiftly enacted when Florence joined the musical comedy sextet, the ‘Globe Trotters’ and began her travels through South East Asia and China under the stage name of ‘Miss Bobby Broadhurst’. Membership of other musical theatre troupes followed along with favourable reviews of her singing and Charleston dancing abilities. These experiences led to the establishment of the Broadhurst Academy in Shanghai, a business offering the booming expatriate population tuition in various arts ‘all the rage back home’ including violin, modern ballroom dancing, banjolele playing and journalism.

During a brief sojourn back in Queensland in 1927, Florence was involved in a car accident – the resultant head injuries putting paid to her singing career. Undaunted, she travelled to England in October of the same year. In 1929 she married Percy Kahn, a stockbroker, with whom she directed Pellier Ltd, Robes and Modes, a high-end boutique in New Bond Street, London, under the assumed name of Madame Pellier. The marriage to Kahn seems to have broken down sometime in the mid-1930s and while working and designing at Pellier, Florence met Leonard Lewis a handsome diesel engineer, and by 1939 they were living in rural Surrey.

In World War II Florence contributed to the war effort by offering hospitality to Australian soldiers abroad through volunteer organisations. Returning to Australia in 1949 with Lewis and their son Robert, a relocation possibly prompted by an infidelity on Lewis’ part, Florence launched into her third career, that of landscape painter and society hostess. Travelling through central Australia, Queensland and New South Wales, she was a highly prolific painter, but perhaps a better self-promoter, with a reviewer commenting on her solo exhibition in 1954 at David Jones Gallery; ‘She does not understand the true character of the landscape she paints, that her eye, indeed, only devours surface beauties, skin deep at best’. Despite establishing Australian (Hand Printed) Wallpapers Pty Ltd in small premises behind Lewis’ motor business in St Leonards, Broadhurst continued to pursue her fine art career. She participated in group exhibitions, entered the Sulman Prize in 1956, the Archibald in 1962 and 1966 and the Wynne in 1964. It is likely that during this time, either through mutual acquaintances or through her socialite activities, that Florence met Joshua Smith, who first painted her portrait for the Archibald Prize in 1962 and this portrait in 1968.

The 1968 portrait depicts Florence with her characteristic auburn bouffant wearing a plain orange knit top – a stark contrast with photographs taken at the time which repeatedly show Florence with bigger hair, a great deal more make-up, wearing brighter, bolder patterns and hands festooned with antique jewellery. The message this image sends out is of quite a different order. The real reasons behind this rather Spartan presentation, like so many other things about Florence Broadhurst, will remain a mystery. The focal point of the portrait is the gold wedding band on her left hand held aloft – an interesting focus when her erstwhile husband Lewis had been living in Queensland since 1964.

The nexus between artist and subject might go some way towards explaining the gulf between the ebullient public persona of Florence Broadhurst and the modest woman depicted here. Yve Close, a painter who had a close twenty-year association with Joshua Smith has said that for Smith the aim of all his portraits was ‘the importance of a viewer sensing the intrinsic personality housed within the outer façade’. Dame Mary Gilmore, a friend, champion and portrait subject of Smith’s wrote; ‘Mr Joshua Smith does bring out the inner dynamics in portraits. For you remember the personality of the sitter, more than just the face. And it is the personality that is the subject, if a painter can paint a portrait as it should be painted’.

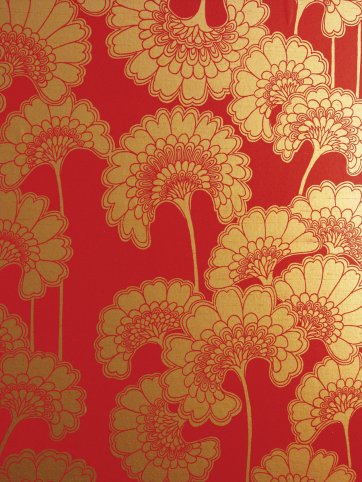

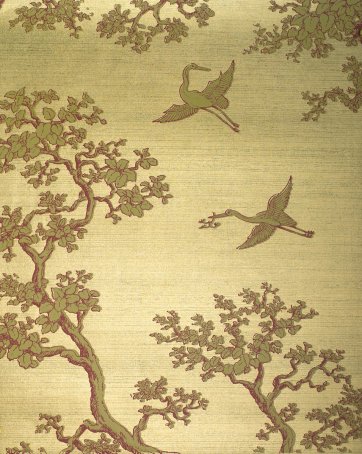

Between 1959 and October 1977 Broadhurst Designs produced a phenomenal 530 hand-drawn patterns for silk-screened wallpapers of great diversity and complexity. Her company was known for its innovation and ability to adapt distinctive wallpaper designs from the latest trends coming out of Europe and the United States and blending them in sometimes startling ways with traditional motifs. Yet was Broadhurst herself the originator of this vast array of designs? The answer is yes and no – although it is her name that adorns all the fabrics and papers that came out of the business, Broadhurst’s team of young, often previously inexperienced artists were most likely the ones that executed the final designs from her original concept. Business was booming and certainly no one denies she had a great eye for design, with Florence calling her revolutionary handprinted creations ‘vigorous designs for modern living’. All this came to an abrupt end when, on 16 October 1977, when Broadhurst was murdered in her Paddington wallpaper showroom. Helen O’Neill’s book, Florence Broadhurst: Her Secret and Extraordinary Lives and Gillian Armstong’s docu-drama, Unfolding Florence (both 2006), posit two different possible scenarios for Broadhurst’s murder – both equally compelling – yet the case remains unsolved.

In this portrait, in artist and subject, we see the convergence of two lives marred by controversy: Joshua Smith’s reluctant involvement in the ‘Dobell Case’ would have long-lasting effects on his confidence and precipitate his self-imposed withdrawal to the fringes of Australian art, despite numerous commissions following his own Archibald win in 1944. The multiple mysteries surrounding Florence still linger to this day, one of which is the true authorship of her prolific design output; another the tragic and brutal nature of her unsolved murder.