Andy Warhol’s predictions about the future can almost be taken for granted today thanks to the development of the World Wide Web. From its very conception the internet has proven a very attractive medium to contemporary artists from around the world, initially as a underground tool for those working under strict political regimes, but more recently for the potential it offers to reach a global audience almost instantaneously. Artists engaged with portraiture are amongst those who have embraced the internet’s universal reach.

In March last year, the biggest portraiture project in the world was staged in conjunction with the Adelaide Festival. The project entitled The Peoples’ Portrait by the American media artist Zhang Ga was a development of his original work created in 2004 during Singapore’s seni Art and Contemporary Festival.

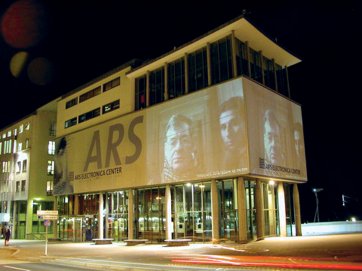

The Peoples’ Portrait utilised the internet to create a worldwide portrait of ordinary people rendered in real time and displayed instantly and simultaneously in the cities of New York, London, Beijing, Linz, Seoul and Adelaide. The subjects of this massive portraiture project were members of the general public who engaged with the art work by taking their own self portrait in digital photographic booths at each venue. These self portraits were then transmitted via the internet to an image database on a central server. They emerged again from this server as individual parts of a flurry of faces from around the world; a truly global portrait. Each face was rotationally displayed every few seconds as large scale projections on buildings in each of the participating cities as well as appearing on various participating websites for the term of the exhibition.

In 2001 the internet artists Eva and Franco Mattes, who go by the name 0100101110101101.org, produced an internet portrait called Life Sharing. The project turned 0100101110101101.org’s shared computers into an open server, a computer accessible across the internet with no passwords or verifications needed. The artists involved with 0100101110101101.org posited that their computers’ contents reflect human psyches, experiences and bodies in the form of aggregations of data. They argue that ‘a computer, with the passing of time, ends up looking like its owner’s brain.’

By sharing the inner mechanisms of their computers with the world, 0100101110101101.org artists are presenting us with an intimate self portrait which the viewer can enter into, engage and interact with, utilise or simply observe. No longer is the realm of portraiture only present in the space between the viewer and the observed; this digital artwork presents us with a kind of interactive living portrait, never static and always evolving.

Another of 0100101110101101.org’s projects, created in 2006, which plays with the conventional notions of portraiture is a series of portraits, not of real people, but of their avatars. The word ‘avatar’ came into use in the eighties and nineties to indicate the symbolic projection of a videogame player in the game setting.

The Portraits series was first exhibited in a virtual gallery called Ars Virtua within the internet world Second Life. Ars Virtua was a computer generated replica of the physical space at the Italian Academy at Columbia University in New York. In a twist on the idiom ‘art imitating life’, the show opened in the virtual space fifteen days prior to the show entering the real world in physical form; meaning that the real-world show was a reproduction of the virtual one.

Despite the challenge the brave new world of digital art appears to present to the traditional notions of portraiture, these artworks are not as radical as they might first appear. Of the Portraits series, 0100101110101101.org observed; “We see avatars as ‘self-portraits’. Unlike most portraits, though, they are not based on the way you ‘are’, but rather on the way you ‘want to be’”. This statement could easily be applied to many more ‘conventional’ forms of portraiture. We have only to look at the oil portrait of Captain James Cook by John Webber in the National Portrait Gallery collection to remind ourselves that portraits are always constructs of the subjects, whatever medium they are created in.

In this brave new world, it is worth bearing in mind that it may not be your physical form that achieves your fifteen minutes of fame; it will most likely be a digital one.