It is a curious fact that John Brack, once regarded as the archetypal Melbourne artist, has emerged in the last ten years as truly national figure. In part this recent celebrity is due to his prominent place in the market – a factor of his limited production and the record prices achieved since the auction of his iconic painting The Bar 1954 last year and again with the auction this May of The Old Time 1970 when the painting became the highest priced Australian work of art ever sold.

However Brack’s national stature has more to do with a belated appreciation of his evocation of a genuine Australian experience. Brack’s work is no longer seen as satirical and anecdotal (his protestations to the contrary at the time were to no avail) or even conventional observation. His unsentimental eye, sharp edged wit, penetrating and pointed descriptions are now appreciated as illustrating an authentic portrait of post-war Australia populated by real characters, unequivocally and honestly viewed.

An exhibition of John Brack’s portraits will be on display from 24 August to 18 November 2007 at the National Portrait Gallery. The exhibition will investigate the place of portraiture in Brack’s oeuvre and his approach to making portraits. Works in a variety of media will be included in the display to demonstrate the breadth of the artist’s practice and how he capitalized on the unique properties of each medium to create his portraits. The National Portrait Gallery is working closely with Helen Maudsley Brack, the artist’s widow, to research the background to each of Brack’s portraits and his relationships with the sitters. Helen Brack has agreed to contribute an essay to the catalogue of the exhibition, as has Dr Sasha Grishin, author of the definitive publication on Brack, The Art of John Brack.

Brack is often misunderstood as aloof, a sardonic hand guided exclusively by his head, taking a critical and acerbic view of the world around him. This is probably more a response to his hard-edged linear style than his subject matter, and as much to the fact that his work does not exhibit the sentimentality that is all too common in Australian art, where sentimentality is commonly equated with beauty. Brack’s painting of Collins Street 5 PM, his best known work, shows the daily parade of tired, alienated office workers returning home. His aim is not satire but to record the changing moods of humanity through the faces of individuals. Brack documented office workers, ballroom dancers, jockeys, brides, bars and drinkers, shopfronts and housing estates, nudes, and the many faces of Melbourne’s inhabitants in his commissioned portraits and his portraits of friends and family. That so many of the artist’s portraits depict friends, family and children will surely cast Brack in a new light.

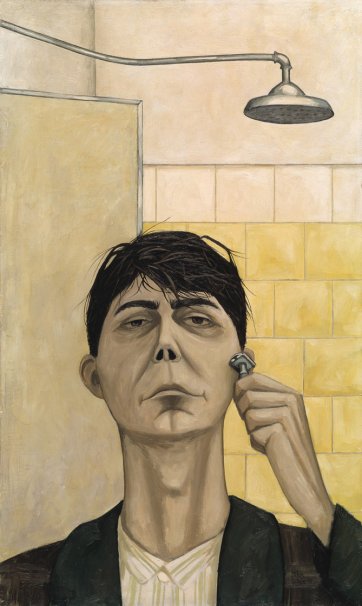

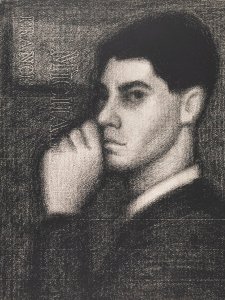

Amongst the earliest works in the exhibition is a self portrait from 1950. This conté drawing shows the typical image of a young artist, alert, curious and questioning of self while absorbing the lessons of a mentor, in this case French artist Georges Seurat, master of solid form and subtle tone. Brack’s later painting, Self portrait 1955 is, in contrast, the objective and unsentimental image of a mature artist, viewed in a domestic situation as he would inevitably see himself every morning in the bathroom mirror. With the exception of the early self-conscious portrait, Brack’s self portraits tend to be extremely self-effacing. Like film director Alfred Hitchcock, he makes cameo appearances in his works – as a shadowy customer in such well-known paintings as Menswear 1953 and The Bar 1954 but more directly in paintings like Still life with Self Portrait 1963. The presence of a self portrait is not immediate in this painting but ultimately the reflection of the artist in the shopwindow is discernable. In that sense the painting echoes the experience of window shopping and the discovery and shock of being observed by one’s own reflection. This is taken a step further with Inside and Outside 1972 where the artist’s presence takes the form of a ghostly image mirrored in the window pane which is repeated on the shiny sides of the goods in the display.

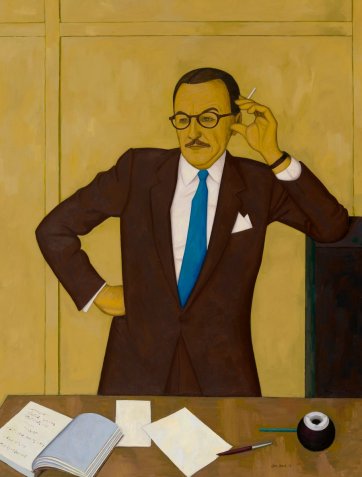

The earliest portraits in the exhibition, the 1950 self portrait drawing and the Portrait of John Stephens 1947, show Brack finding and developing a style. Brack’s mature portraits are quite different from the work of other artists – his powerful and graphic use of line to delineate features is unmistakable. His confident line is so assured that is almost as if it’s drawn by heart rather than from observation. His portrait of Adelaide art dealer and jazz enthusiast, Kym Bonython for example, is poster-like in its uninflected colours and direct, frontal composition. Brack paints portraits that are sparse and cool, honest but not necessarily flattering. He avoids warm tones, endearing smiles and status enhancing accessories. He favours a pictorial rigour and builds a solidity and strength into his compositions to promote the central importance of the sitter. His is an almost puritan aesthetic that would never allow ornate detail to detract from the impact of his chosen subject. Brack’s lines are firm to the point of impassive but he imbues his sitter with life in the twitches and nuances of pose. While the subject is central, the sitter is often situated just off centre and seemingly off balance. Brack discloses mood though pose and colour using composition as projection of personality and to create a psychological dimension in his portraits. This approach is exemplified in his portrait of Hal Hattam, one of the artist’s most significant portraits, in which the sitter is pushed to the shadows at the top of the canvas to create a disturbing and emotive mood.

The exhibition provides a showcase for the range of media used by Brack in his portrait making. There are major works using oil on canvas as well as works on paper including watercolours, pencil and conté drawings and etchings. Brack adopted a traditional, almost old-fashioned approach in crafting his paintings. He inevitably worked up the composition from detailed sketches to produce highly finished studies in order to test the composition. This approach risks spontaneity, but gives his work a weighty graphic power and polished finish. The National Portrait Gallery exhibition of Brack’s portraits will, in a number of cases, bring the painting and preparatory drawings together to illuminate Brack’s portrait-making process. The Portrait of Harold Hattam provides a particularly dramatic example of this process; the initial studies vary greatly from the final painting as Brack grappled to best portray Hattam’s complex character.

While on some occasions the preparatory and finished works vary during the working up process, most exhibit but small differences and instead show how the study allowed Brack to trial the final composition and palette on a reduced and economic scale in order to predict the success of the painting. The few compositional differences between the study and the finished paintings indicate that Brack made many explorative sketches first before he made the studies, and indeed this is the case. The Portrait of J R McLeod 1971 provides an illuminating case history in allowing the portrait process to be seen from the very start. A selection of five sketches, chosen from over twenty Brack made in working up the portrait, shows the artist getting a feel for his sitter and records the developing relationship between the two. A highly finished conté drawing followed, allowing the artist to work out the final details of composition and scale before he commenced the final painting of McLeod.

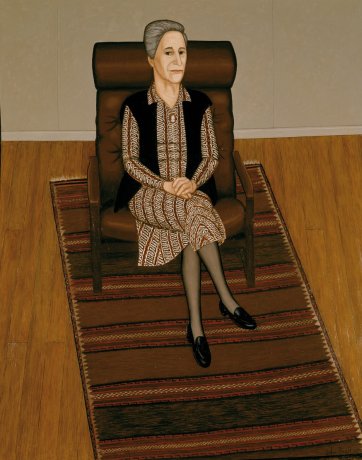

While Brack is invariably objective in all his portraits – he had a gift for noting habits and posture – there is a tangible sense of formality and distance in his commissioned portraits that is absent in the portraits of friends and family. This subtle difference is apparent when comparing the similar portraits - the commissioned Portrait of Joan Croll 1976 in the Gallery’s own collection and that of ngv curator and friend, Dr Ursula Hoff, done in 1985. Brack had first made a powerful and sympathetic drawing of Hoff’s face in 1954 almost 30 years before he painted the full-length seated portrait. The connection of friendship shows and the portrait of Hoff is softer, somehow more intimate and revealing.

Brack put great effort into his commissioned portraits but when he depicted friends and family, there is an ease that is quite discernable and an immediate and rewarding intimacy. Recognising the fierce independence of a tiny child in Brack’s etching Third Daughter, any parent’s heart must melt. There is real joy and pride in his many depictions of family: Brack shows his children as babies, as girls and as young women and his wife Helen as model, mother and muse. While ostensibly displaying his subject, all of Brack’s portraits inevitably expose the artist himself as a reserved and private man. The varied moods in his portraits chart his reactions to professional relationships in commissioned work and equally reveal the emotional responses to his familiars, sitters who were friends and family. His rigorous compositions are based on observation yet always look like they are drawn by heart.