It is a simple proposition that there is greater scope for a writer to describe the life of a painter, the act of painting, and the appearance and significance of paintings, than for a painter to represent the character of an author, the act of writing, or the nature of a writer's works.

Undoubtedly the most extended and discursive description of a young man's education in art - along with most other aspects of experience, apart, notably, from work - is contained in the many volumes of Proust's In Search of Lost Time. Its unnamed protagonist recalls a canvas he has seen in the studio of the painter, Elstir:

The river, the women's dresses, the sails of the boats, the numerous reflections between the various elements in the painting all fitted together on the square of canvas Elstir had cut out of a wonderful afternoon. The marvellous shimmer on the dress of a woman who had stopped dancing for a moment because she was hot and out of breath was reflected too, in the same way, in the cloth of a motionless sail, in the water of the little port, in the wooden landing stage, in the leaves on trees and in the sky … [The painter] had been able to arrest the passage of the hours for all time in this luminous moment when the lady had felt hot and stopped dancing, when the tree was encircled by a ring of shade, when the sails seemed to be gliding over a glaze of gold.

In In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower, Elstir shows the protagonist, bored at the prospect of attending the races, how he would salvage the day:

Take that particular figure, the jockey, the centre of attraction: down in the paddock where he looks so dull, so featureless in his glowing colours, at one with the horse, reining it in as it wheels about - yet wouldn't it be interesting to grasp the technical movements he makes, to show the bright blob he makes, along with the glossy coats of the horses, out on the turf! … The first race meeting I went to was especially magnificent, with women of exceptional elegance, amid a wash of moist light, a Dutch light, and you could sense the penetrating chill from the water reaching up into the sunlight … How I wished I could capture it! I went home from that race-meeting with my head reeling, bursting with the urge to paint!

Even if it were concerned with nothing but art, In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower would not simply be 'about' a painter, paintings or the experience of looking at paintings. The narrative is itself imbued with painterly effects, which reach a magnificent climax on the final page as hotel curtains part to reveal a seaside town on a summer's day appearing as dead and immemorial as a mummy, magnificent and millennial, carefully divested by our old servant of all its wrappings and laid bare, embalmed in vestments of gold. Achieving such integration between subject and form is more often than not unenjoyable for a writer. David Marr relates how Patrick White, for a time, attempted to write 'as a painter used paint, laying down prose in impasto or thin wash or skeins of abstract colour'. This sounds lovely, but in practice White envied visual artists their materials and their capacity to work at speed, complaining that writers lack 'such a lovely sensuous material to play about with in expressing ourselves. I do loathe sitting at my desk day after day week after week year after year grinding out novels greyly.'

White described the preoccupations and frustrations of a visual artist in his long novel of 1970, The Vivisector, dedicated, in part, to Sidney Nolan. In several passages of that book the process of painting is described. In this hectically erotic one, the author's struggle to represent an artist piles upon that of his fictional protagonist, Duffield, who is trying to paint his teenaged piano prodigy lover and imbue his work with the music she makes:

He began that afternoon. At times he heard his panting, or groaning, or wheezing (a bronchial old age?) as he thrust against the virgin board. There were the other moments after the initial terror, when it became so exquisitely easy he could feel the flesh returning to his face; the sweat tasted deliciously salt, which his tongue lapped from a corner of his mouth. In the same way, his possessed girl was beginning to create in spite of herself. The inclining body was both exhilarated by the music escaping out of it, and tormented by what might escape altogether. Avoiding the accusation of technique and emptiness, he must somehow fill the rectangular board with a volume of music. It was their common problem: the girl appeared to writhe, to one side, as she crouched at her piano. The piano remained a dead expanse. The candlesticks he could build up with a brilliance of verdigris and icicles of wax; but he couldn't so far bring the bloody piano to life. Yes, bloody. He drew blood: slashing, and gashing; and retreated from the thing he had so foolishly undertaken.

The Vivisector is shot through with the idea that the sensations and experiences of the painter are only halfway lived until they are laid out, transmogrified, on canvas. A photographer will often convey the sense of vital integration between artwork and artist concisely and dispassionately, simply by including the artwork in a portrait of the artist.

Amongst a dozen or more such photographs in the National Portrait Gallery collection are photographs of Leonard French piecing together a stained glass panel, John Perceval painting Veronica and the conspirators, and Marea Gazzard building a bowl with a snake of clay. In one of the Gallery's few paintings of an artist at work, Albert Namatjira 1958, Sir William Dargie has depicted his friend working on a canvas in the desert. Interestingly, although Namatjira is depicted in Dargie's usual no-nonsense detail, the portraitist has deliberately made the painting he is holding sketchy and blurred; propriety, perhaps, has led him to refrain from reproducing the work of a fellow artist on a miniature scale. In all these portraits there is a physical engagement between the sitter and his productions - the sculptor with her hands in the clay, the maculate shirt of the painter. Moving our gaze between the face of the artist and the art work transuded from his or her imagination, we like to think that we form an enhanced notion of the character and sensibility of the subject. The awkward truth is, however, that although writers and artists both belong to the category of creative individuals, this portrait strategy is not transferable to the representation of an author. How is an author to be shown 'bursting with the urge' to write, or at his or her work of 'grinding out novels greyly'? A painter can hardly resort to picturing a writer with one of his or her books; the resulting image would look more like a promotional shot taken at the request of a publicity agent than an intimate examination of the creative process. With a typewriter - staring into a computer monitor - at a desk - with pen archly in hand, in the inimitable manner of Vermeer's A Lady Writing? Nine out of ten artists would reject the blatancy and compositional limitations of such poses and props. By elimination, an artist charged with representing a writer is bound to aim at conveying a cerebral countenance; or a look of impatience with ordinary discourse; or a heightened imagination; or even, sometimes, a yarning loquaciousness.

These strategies are variously employed in the Gallery's collection of painted portraits of Australian writers. Bernd Heinrich has chosen to portray Thomas Keneally using text from Keneally's Booker Prize-winning novel, Schindler's Ark, in the background of his large, highly coloured portrait. Heinrich recalls that the author had just been running on the beach when he arrived for a 'sitting'; though there was obviously time over the course of the portrait's creation for him to change, Keneally presumably chose, and Heinrich agreed for him, to be portrayed in his unintellectual getup of tracksuit pants and sneakers. It is difficult to look at this picture in the gallery without feeling bailed up by the author. It is as if he is about to speak to us in the sincerest tones, his face wearing its characteristic look of eager, almost childlike openness, his hand held over his heart and his body starting out of the picture plane. Many artists in the 1980s were using text in their works, foregrounding words as mere typography, or as loaded with meaning, be it banal or sparely profound. Text in art has proliferated since then, as a recent issue of Artlink devoted to 'the word as art' demonstrates. Heinrich's painting of Keneally is no piece of Conceptual art. It appears to be a very simple, straightforward work, identical in approach to a portrait of a visual artist depicted with his own productions, aiming only to represent its sitter as unambiguously as possible as a writer. Like Dargie in painting Namatjira's painting, however, Heinrich has made his text obscure; though they appear to be written in a sharp, legible longhand, it is in fact very difficult to make out the words he has inscribed on his canvas. Laden with a seriousness that is hence sensed rather than read, they function as a portentous trace of Keneally's text, without eclipsing the apparently disingenuous figure of the author.

In three portraits from the collection that are compositionally similar to one another, the artist has chosen to portray the author as a hard chair-full of challenging intellect. In his portrait of Robert Dessaix Robert Hannaford has set up a very sparse room, like one seen in a dream, before setting the author a good way back in it and depicting him with his characteristic realism. Frankly declaring that this-is-a-portrait, Dessaix sits on a platform, his gaze cool, slightly defensive, his hands clasped in front of him. He looks discomfited, but determined to hold his eye against that of the viewer, with his chin raised in apparent defence, defiance, or arrogance. There are props indicating Dessaix's profession - some books, a pencil, what looks like a bottle of glue - but he is dressed in a leather jacket rather than the more comfortable apparel conducive to writing, looking as if he is about to go out, or has just come in, rather than as if he has been disturbed in the act of creating. It's anything but a cosy representation, and Dessaix himself looks aloof, chilly as his austere surroundings. Dame Mary Gilmore is depicted as forbidding, pugnacious and resolute by popular painter Lyall Trindall, a barber before he turned to portraiture with 'sincerity as [his] guiding principle'. At the time the work was painted, Gilmore had given up the editorship of the women's page of the Australian Worker and published The wild swan, a book of verse excoriating white settlers who had ravaged the land and eviscerated Aboriginal culture. Recently created DBE, she was assembling the poems in Battlefields (1939), the title referring to her interventions in many causes.

The late Elizabeth Jolley, depicted by Mary Moore as dementia began to claim her, stares with a kind of dispassionate enquiry at the viewer. Those who knew her at the height of her remarkably productive and generous career miss the energy they remember in her; but Moore's is a portrait of imprisoned intelligence and eroded wisdom, a tribute to Jolley's achievements made at the time when she, herself, was having to let them go.

Helen Garner, unlike Dessaix and Gilmore, looks snugly sunk into her soft sofa in one of a trio of portraits of writers making a gesture that has long connoted thoughtfulness - resting fingers or a hand against the face. Like poet Les Murray, sucking ruminatively on a finger, Garner looks as if she has been painted at home in her own living room. The portrait was made before the publication of Joe Cinque's Consolation (2004), a book adding substantially to the body of profound ethical questions with which Garner has confronted Australians. A middle-aged woman represented without flattery, she turns around as if the artist, Jenny Sages, has just come through the door. Her hand is against her cheek; apparently disturbed in the act of working something through, she seems irritated by the interruption. Like Keneally, she seems about to speak, but pithily, not discursively. Her glance is one of intelligent evaluation, tinged with impatience. Even a viewer unfamiliar with her novels and deeply moral non-fiction would surely see in this portrait a person exasperated by fools.

Murray Bail, once married to Garner, is depicted with his hand to his chin in one of the most striking of the portraits Fred Williams made of his circle of friends. Painted some years after Bail had published Contemporary Portraits and Other Stories, it was completed soon after the publication of his first novel, Homesickness (1980). Represented as a slight, rumpled, ordinary chap, the writer looks diffident, even a little sheepish, but at the same time a man who may conceivably be cogitating a low-key story strangely irresistible to the listener. Hesitant yet seemingly shrewd, he does not exert the fascination of the unnamed protagonist of his Eucalyptus (1998), 'nothing like a suitor', who materialises between the trees and slowly cultivates the interest of a girl whose father has warned to 'beware of any man who deliberately tells a story … it's worth asking, when a man starts concocting a story in front of you. Why is he telling it? What does he want?' This portrait came about after Williams and Bail had met on the Council of the Australian National Gallery in the late 1970s. Thirty years later, it has emerged as a particularly felicitous combination of sitter and artist, as it has transpired that the art of each has brought about a definite change in the way many Australians view their landscape. In his columnar abstract paintings of Sherbrooke Forest Williams extracted the very essence of forest gums. Bail wrote an elegant novel constantly drifting away from, and returning to, such trees: 'Silver light slanted into the motionless trunks, as if coming from narrow windows'; 'Here on the tapering flat were many rare eucalypts now fully grown, a secret abundance … flowering in a mass of gaudy asterisks.' Twentieth-century abstract art emerged partly from artists' rejection of painting as a means of telling a story. In a recent essay, 'The Chinese Painter as Poet', American scholar Jonathan Chaves examines centuries' worth of notions of the 'sister arts' of poetry and painting, from the Greeks Simonides and Horace, through the Chinese scholar Su Dongpo and the German man of letters Gotthold Lessing to the nineteenth-century English writer Matthew Arnold. The Chinese had long considered writing a more elevated art than painting; expressing the fundamental point that 'painting is the art of depicting the eternalized moment, while poetry is the art of depicting the flow of time', Arnold, too, judges the poet the superior achiever through his capacity to 'capture the stream of life's majestic whole'.

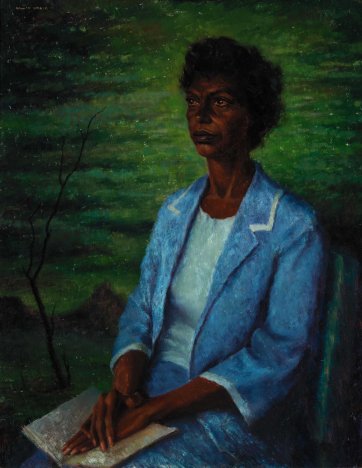

Two portraits of writers in the collection are particularly evocative of the sitter's imaginative process. Clif Peir's Kath Walker - Aboriginal Poet sits very composedly in her Chanel-style suit, her slender hands folded on a book in her lap. Throughout her life, Walker aimed to promote cultural pride amongst Indigenous people through her writing, which she described as 'sloganistic, civil rightish, plain and simple'. Though the portrait as actually made while she was staying with the Peir family in suburban Oatley, NSW in the mid-1960s, her gaze is far away, to a vague green landscape suggesting the Queensland island where she was born and to which, as Oodgeroo Noonuccal, she increasingly returned in later life.

As its name, Peter Carey in Kelly Country, makes explicit, Bruce Armstrong's portrait of Peter Carey is intended as a portrait of a work germinating in the mind of its creator. Carey is like a nervous animal in the dry landscape, but he wears an incongruous outfit that would be more at home in New York, where he was living as his Booker Prize-winning True History of the Kelly Gang (2000) came together, than in rural Victoria. These two writers are represented as absent, immersed in the imaginary or remembered worlds growing within them, the distillation of which will flow onto the page. Neither looks firmly fixed, or present, in the portrait. Generally, one of the great pleasures in looking at portraits is being able to stare directly, searchingly into the eyes of the sitter. Both Peir and Armstrong, however, have succeeded in producing evocative, definitive portrayals that subvert this engagement, each replacing it with an insight into the restless intelligence of his subject. Though more open to popular criticism, the portraitist's is an extension of the challenge facing many other kinds of artists. Patrick White's incapacitated, old Duffield asks a younger, presumably abstract painter what he aims to achieve. With reckless candour he replies 'Well, I suppose I'm sort of trying to realise a feeling or a thought or emotion in pictorial terms sort of.' 'You? Balls!' He couldn't make them round enough. 'Don't tell me!' So shaken the vibrations must have burst through. 'You! The first and only!'

Chaves relates that ' "Gu Kaizhi once said, 'to paint "The hand sweeps over the five-stringed lute" is easy, but to paint "The eye escorts the homing goose' is hard." ' There are many long novels - The Vivisector, In Search of Lost Time and Ulysses amongst them - which are overwhelmingly concerned with the thoughts and observations of a protagonist whose outward appearance remains virtually undescribed. By contrast, for a visual artist, rendering the facial configurations of the author is easy. The hard part is rendering the intellect and imagination that lies beneath the visage, the achievement that is independent of appearances.