I first met Sidney Nolan around the time he painted this self-portrait. I had seen him distantly before and in 1988 I was working on an exhibition for the National Gallery of Australia (Sidney Nolan Drawings) which gave me the opportunity to meet with the artist to talk about his drawings and collages.

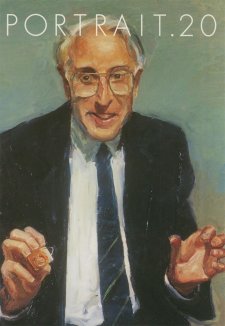

Our first meeting was in the room he was staying in at the Intercontinental Hotel in Sydney. We discussed photographs of drawings spread out on a hotel table. He was dressed only in a hotel bathrobe. My overwhelming first close impression of him was that he was very pink. White hair over a mottled pink skin. He was an artist who defined a particular glaring light (the light of ‘high noon’ as he said of his landscape Kiata), but the Australian sun was not kind to Nolan’s fair skin. Nolan’s pink complexion is captured with great accuracy in the 1988 self-portrait. The painting alternates between pink and a bruisy blue; the colour scheme conveys a fleshy quality. The shape of the head is also descriptive, the back of the head carrying the shape of Nolan’s mid-length lock of wispy hair. He creates an oscillation between the head seen in profile and in three-quarter view, a cubistic device he used throughout his career present in his transfer drawings made as early as 1940. The work carries other echoes of earlier works, in particular of Nolan’s pastel profile drawn used as the dusk-jacket illustration to Max Harris’s surreal novel The Vegetative Eye, published in 1943. In that drawing the artist had used a looped and smudged thicket of coloured lines to suggest the features of the face, not unlike the way he uses paint in the self-portrait. The earlier drawing may also have been a self-portrait.

Nolan made numerous self-portraits during his career, the most well-known of which is now the 1943 painting now in the collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales (the only Australian work to have been included in that Gallery’s recent survey of self-portraits undertaken in collaboration with London’s National Portrait Gallery). The 1943 self-portrait is a direct frontal portrait painted in bright primary colours on a rough canvas. It was painted at Dimboola during Nolan’s army service in the Wimmera. Its simplicity belies a highly complex work in which the artist not only declares his determination to be regarded as an artist (rather than a soldier). Furthermore he experimented with the idea of compressing landscape space into something inscribed onto, rather than around the face.

The 1943 self-portrait is one in which the artist describes his visage and his activity as an artist. Yet he went on to produce much more complex forms of self-portraiture. It could be argued that the entire Ned Kelly series that preoccupied him throughout the mid-1940s is an extended form of self-portrait.

In later life, Nolan admitted that the Kelly series was as much about his own early life as about the history of the bushranger, yet he remained close about the autobiographical reading of the series, preferring to focus on the formal inventiveness of the paintings. Nolan’s elusiveness was undeniable and something of that quality comes to the surface in the 1988 self-portrait.