David Gwinnutt (b. 1961), whose photograph of a young Leigh Bowery has recently been acquired by the National Portrait Gallery, studied fine art at Middlesex University before moving to London, the club scene of which he began recording in the early 1980s.

In a front page article on his work in London’s Independent magazine in 2000, he recalled the mood of the time:

‘There was a lot of peer pressure. It was a kind of race to see who could become famous first. Everyone reinvented themselves constantly. I imagined I was going to be the Cecil Beaton of my generation.’

Leigh Bowery (1961-1994), London-based nightclub performer, costume designer and muse was born in the Melbourne suburb of Sunshine, and attended school in Melbourne before briefly studying fashion design at RMIT in 1980. He moved to London, where he was to work his way up to a position of trainee manager at Burger King. In 1982 he began selling clothes he had made at Kensington Market. In 1983 he performed at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts; the following year he travelled to New York and Japan to show his clothes. He first performed at a club in 1984; in 1985 he initiated the aptly named club, Taboo, within Maximus nightclub in Leicester Square. In and interview on the ‘Leigh Bowery extravaganza’ website, Matthew Glamorre, on-time musical collaborator of Bowery’s and now leading London nightclub impresario, describes the scene at Taboo nights:

‘Taboo was incredible… it was my first experience of what a seminal club feels like. The danger, hysteria, extreme fashion & excitement – it was insane. The feeling of being ‘IN’ but strangely ‘OUT’ cos you never really felt accepted. At first I was frightened by it but it was like a drug – the adrenaline of getting ready, surviving the journey there (walking or on the bus/tube), getting in & then getting wasted, having loads of fights, falling about on the floor…’

Taboo closed after just over a year, while it was still one of the city’s most fashionable destinations. Through the rest of the 1980s and the early 1990s, Bowery’s performances, both alone and in aggregates such as the Quality Street Wrappers, Raw Sewerage and Minty, became increasingly elaborate, obscene, threatening and hilarious. In his most renowned phenomenally physically taxing act, he ‘gave birth’ to a full-sized accomplice, his wife Nicola Bateman Bowery, in a revolting yet strangely affirmative drama. One of his last performances saw him hanging upside-down in mid-air, his naked body bristling with clothes pegs, before crashing climatically through a plate of glass.

Bowery designed for dancer and choreographer Michael Clark for ten years, and for performers including Boy George, who later wrote a musical in which the character of Bowery featured prominently. On occasion he collaborated in various ways with other designers, including Hanae Mori and Rifat Ozbek. Principally, however, his own clothes and makeup were his art, his body his medium and his artistic preoccupation. Not only a visionary designer, but an intelligent pattern maker and machinist, he would work for days and nights on and outfit in which he would appear only once. The originality of his creations, never straight ‘drag’ outfits but always comprising a subversive, unsettling element, has seldom been equalled. Absolutely central to London’s fashion scene over a decade, Bowery has been credited with ongoing influence over the designs of Vivienne Westwood, Alexander McQueen, and John Galliano amongst others.

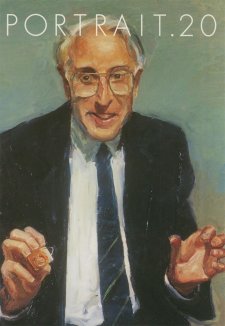

Gwinnutt met Bowery in about 1982, when he took some fancy material to Leigh’s flat to have a shirt made. The next time he saw Leigh, he and his friend Trojan were near Heaven nightclub. They were wearing one of Leigh’s most famous early ‘looks’ dubbed ‘Pakis from outer space’ teaming Indian-style jewellery and painted motifs with blue or green faces, platform boots, striped tights, women’s underwear and more. He recalls they looked ‘oblivious of us and caught up in their own world, chatting and looking in their purses.’ Some time later, Bowery posed for this unusually self-effacing photograph in his bedsitter in Ladbroke Grove. Robert Violette, publisher of a monograph on Bowery, remarks that the performer appears to be conscious of being photographed by a serious photographer, rather than in photo booth snaps or club scene shots which had been the norm up to that point.’

Bowery wore his coat and elements of this makeup some five years later for a series of performances at the Anthony d’Offay Gallery, which was for some time London’s leading dealer in international contemporary art. These gallery appearances featuring Bowery posing in a succession of outfits before a two-way mirror, triggered two significant long-term portrait projects. From 1988 to 1994 his ever-changing appearance was tracked in a series of portraits by photographer Fergus Greer. Moreover, however, from 1990 Bowery posed for painter Lucien Freud, exposing his giant body unadorned for a number of extraordinarily powerful paintings. One of Bowery’s close friends, installation and new media artist, Cerith Wyn Evans, described posing for Lucian as a ‘huge shift upwards’ for Leigh. Added to the artist’s d’Offay performances, Freud’s series of works offered Bowery legitimacy amidst a demographic that had not been exposed to his nightclub performances and looks. One of the most memorable photographs of Bowery taken the year before he died, shows him at the opening of an exhibition of Freud’s paintings at the Metropolitan Museum; before a large back view of his massive naked form, the 188cm Bowery stands in an enormous red, white and blue sequinned floral ballgown, its buckled neckline extending into a tight balaclava mask. His heavenly blue eyes, ringed with heavy black, glare at the first-night crowd from beneath a Kaiser helmet. The outfit is now in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria.

Following his death from HIV-related illness in London – when ‘all the freaks in London’ are said to have gone into mourning, Leigh Bowery was buried in Australia alongside his mother. Since his death, appreciation of the breadth of his influence has increased. He has been the subject of several books and a long article in The New Yorker. Sydney Museum of Contemporary Art mounted the world’s largest survey exhibition of his work, Take a Bowery: The Art and (larger than life) Life of Leigh Bowery in 2003-4, from the catalogue which some of the information this article is taken.

Stephen Willat’s mixed media portrait of Bowery (1984) is in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London; the accompanying caption describes him as an ‘Australian performance artist’.

Through the 1980s, David Gwinnutt photographed many artists, performers and fashion personalities. His work appeared in The Face, Vogue, Interview as well as The Guardian, The New Yorker and Time Out, and one of his photographs is in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London. Gwinnutt has recently participated in an expo about sexual identity and is working on a project symbolising the positive integration of gay people in the UK.