'Michael Leunig is an artist who can capture a sigh and put it down in pen and ink.'

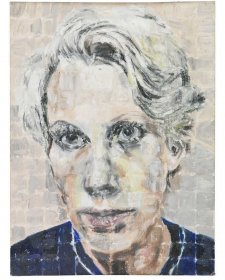

While the name Michael Leunig is familiar to most Australians, the majority of his readership would not recognise him if he passed them while walking down the street.

The face behind the much loved cartoon series, renowned for his philosophical and poetic reflections on life, lives on a farm in eastern Victoria and doesn't own a television. Despite his resistance to the mass media, his insight through his artwork into the human condition and current affairs has become famous Australia-wide.

In our high-tech world fascinated with popular culture, the faces of pop stars, sportspeople and actors are instantly recognisable. Even the identities of some artists, usually better known for being the creators of likenesses, become familiar to the general public through well-publicised art exhibitions like the Archibald Prize at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Portraits of people who are renowned for their achievements outside of the public eye are a more difficult proposition. How does an artist go about portraying the face of a person who is known primarily through their work? In order to solve this dilemma, traditionally many portraits have depicted a subject along with the 'tools of their trade', for example, the palette and paintbrush of an artist, the uniform of a military officer or the crown and garb associated with royal portraits.

The painting of Sir Macfarlane Burnet OM AK KBE by Sir William Dargie in the National Portrait Gallery's collection is unmistakeably that of a scientist, seated as he is in a lab coat at a desk surrounded by all the scientific tools of his trade. Photography often utilises the same devices as painting as is evidenced in the wonderful portrait of Andy Thomas by Montalbetti+Campbell. The photograph of the astronaut striking a heroic pose and wearing an authentic space suit was taken on site at the NASA base at Houston.

Yet one of the more recent acquisitions by the National Portrait Gallery, a photographic portrait of Michael Leunig by Jacqueline Mitelman, gives away very little as to the identity of the sitter. He is not shown drawing one of his famous cartoons, he is not in his studio surrounded by drafts; indeed there is not a pencil or a pen to be seen. All the chiaroscuro photograph shows is a man in his late fifties staring intensely into the camera lens. The expression on the face is difficult to place, but it is somewhere between apathy and concern, pensiveness and reflection, sadness and pathos with a glimmer of underlying wit and humour. Intriguingly, this is the same description that has been used numerous times to describe Michael Leunig's cartoons. In a superbly atmospheric photograph, capturing one single expression with no visual cues or props, Mitelman has encapsulated the essence of this cartoonist's approach to life and his work.

Michael Leunig grew up in a working class suburb of Melbourne. At the age of eight he was very badly burned in an accident whilst playing at the local rubbish tip, leaving him unable to walk for six months and having to undergo numerous painful operations. He recalls the sense of isolation he felt during this period of his life vividly. Cut off from the outside world and unable to play with other children it is easy to see how the feeling of loss and abandonment at such a formative age has seeped into the cartoons he draws.

After a brief stint following his father's footsteps as a slaughterman, his first work was published in the Monash University newspaper Lots Wife 1965, when he was still a student. In 1969 he commenced working with The Age as an illustrator and cartoonist. Each week since then, The Age has published a Leunig cartoon, poetry or illustration, bringing his quirky and insightful views on life and politics into the homes and onto the fridges of millions of Australians. In addition to the weekly cartoons that also appear in the Sydney Morning Herald and the West Australian, more than twenty books of Leunig's poetry and drawings have been published in the last twenty years, along with numerous calendars and fine art drawings. In 2002 Leunig's work was given a three-dimensional life in the Leunig Animated series accompanied by a comprehensive exhibition at the Museum of Sydney. Perhaps the clearest example illustrating Leunig's popularity was the diversity of the audience attending this exhibition; from elderly grandparents through to young children, all flocked through the doors to see their favourite characters from his cartoons.

Each endearing character, lovingly described in pen by Leunig, has a life that springs from the page with the ability to surprise, disturb and inspire both their creator and his readers. Mr. Curly, named for the feature that graces his forehead, lives in the paradoxically named town of Curly Flat and is a happy and optimistic fellow who occasionally writes letters of wisdom to his friend Vasco Pyjama. Vasco travels around the world, often despairing of his circumstances and surroundings but still managing to find joy in unlikely places. He drifts along through life, hoping to find meaning amidst cruelty, perils and depression. Everyperson is a small, wide-eyed creature with a huge bulbous nose. Leunig describes him as a naked angel, ageless and genderless; an innocent messenger-fool presenting no possible threat and therefore permitted to state any case or express any feeling shamelessly.

Michael Leunig recalls fondly the first cartoon he drew in his distinctive style at the very beginning of his career; "One Saturday morning, I was supposed to be doing a Vietnam cartoon, and I just couldn't. I thought Vietnam was such a hideous mess; anything a 23-year old kid said was irrelevant. I wanted to flee from the squalidness and I started drawing an optimistic fantasy about the human spirit ... a man walking along with a teapot on his head, followed by a duck. I'd never drawn such a thing before, the teapot just landed on his head. The editor said he didn't really understand it, but he liked it and ran it. I suppose I was saying that, as the world becomes more disconnected and fragment, I feel this need to re-state what is constant and the teapot symbolised it. A warm, shared, comforting, familiar thing."

The perfect balance of whimsy and melancholy in Leunig's work has taken on a more overtly political nature in the years following the war in Iraq. His repulsion at what he sees as the media's 'Hollywoodisation' of the war means his latest cartoons bring to light aspects of the conflict which other areas of the media do not concentrate on. Despite the fantastical element of his constructed cartoon worlds, Leunig's latest cartoons demonstrate very effectively the essential link between his imagination and the political reality we live in.

It isn't all doom and gloom however. Most ill feeling and despair eases when sitting with a warm teapot on your head and a friendly duck by your side.

"And ducks, well, ducks just waddle along and get on with it, they are pristine and wonderfully self-cleaning, their beaks are smooth and non-threatening, they like food and sex and can be very comical. One of the great English poets wrote, 'From the troubles of this world, I turn to ducks..."