Now in its sixth year, the staging of thrs exhibition at Commonwealth Place provides a timely opportunity for the Gallery to look at the impact of Headspace in school life. Two teachers Heather Prickett and Phil Day whose schools have participated in Headspace a number of times, provided revealing reflections about the significance of this event within their schools.

Heather Pnckett of Black Mountain School, credits Headspace as the catalyst for shifting the way the whole school thinks about art. The cataloguing, mounting, lighting and display of the works in the exhibition added to the school's understanding of its student's work.

'Headspace was the beginning of a vision of how art can widen and deepen student's access to the world. The quality of presentation, the venue and publications help our students understand the value of what they have made. This has impacted on us at school -developing an ethos of value in art. We try to present work well, knowing the significance of doing so to personal and public perception of their work.'

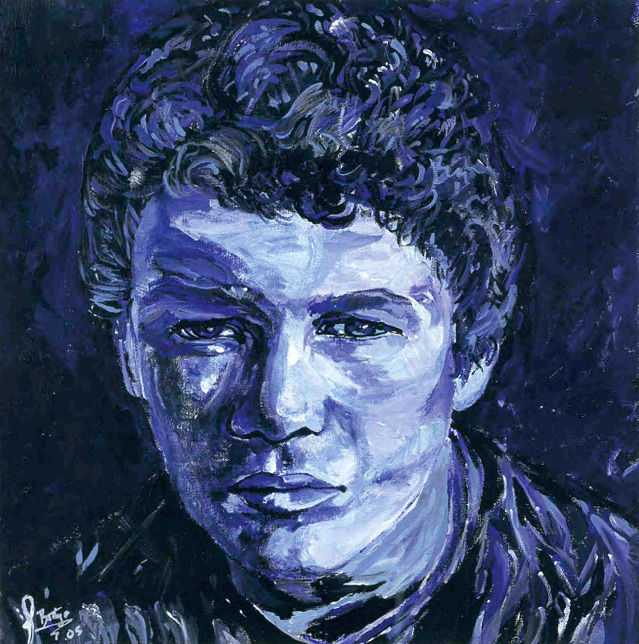

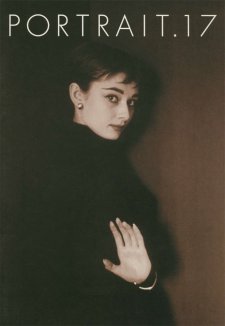

Through Headspace, the Gallery expresses its genuine commitment to fostering a place in the lives of young people for self expression and learning through portraiture. The exhibition itself is the result of careful curatorial planning and partnership development with school across Australia. This year the Gallery received over 900 submissions from which a selection of about 200 portraits were made.

Phil Day from Braidwood Central School sees self-imaging as natural and fundamental to human development. It is a process that allows us to explain, understand and examine ourselves. Headspace formalises this process by providing a museum context for these investigations. Phil explains that 'through Headspace, students reveal subjective truths about themselves.'

The works in Headspace are not marked or assessed by a school body and as such there is no agenda except to provide a survey of the ways in which young people depict themselves. 'Teenagers can pursue teenage interests and tackle complex issues without complications. By this I mean that they don't need to know the difference between baroque and rococo architecture, or how to draw using aerial perspective. The main subject matter for Headspace is themselves ... they have all the information they need.'

This year's Headspace asks a simple question: 'Who am I?' The answer to this question is expansive, allowing students to go beyond a name and personal appearance towards a discussion and exploration of where they fit in the world. Like previous Headspace themes, 'Who am I?' encourages a personal inquiry through which students align themselves with the thinking processes of philosophers such as Nietzsche and Satre. For Phil, the project is open ended. 'Headspace has breadth. You can approach the theme from a number of angles. It encourages you to wrestle with it, rather than stumble over it.'

The National Portrait Gallery thanks and congratulates all of the teachers and students who have participated in the Headspace project since its inception in 2000. Headspace is an opportunity for learning about ourselves: how we perceive ourselves and what we reveal of ourselves. Although we can never fully measure the impact of learning or even speculate about all of the fruits of such endeavours, clearly the processes of self portraiture tap into eternal questions which are as relevant now as they were for Rembrandt or Frida Kahlo.